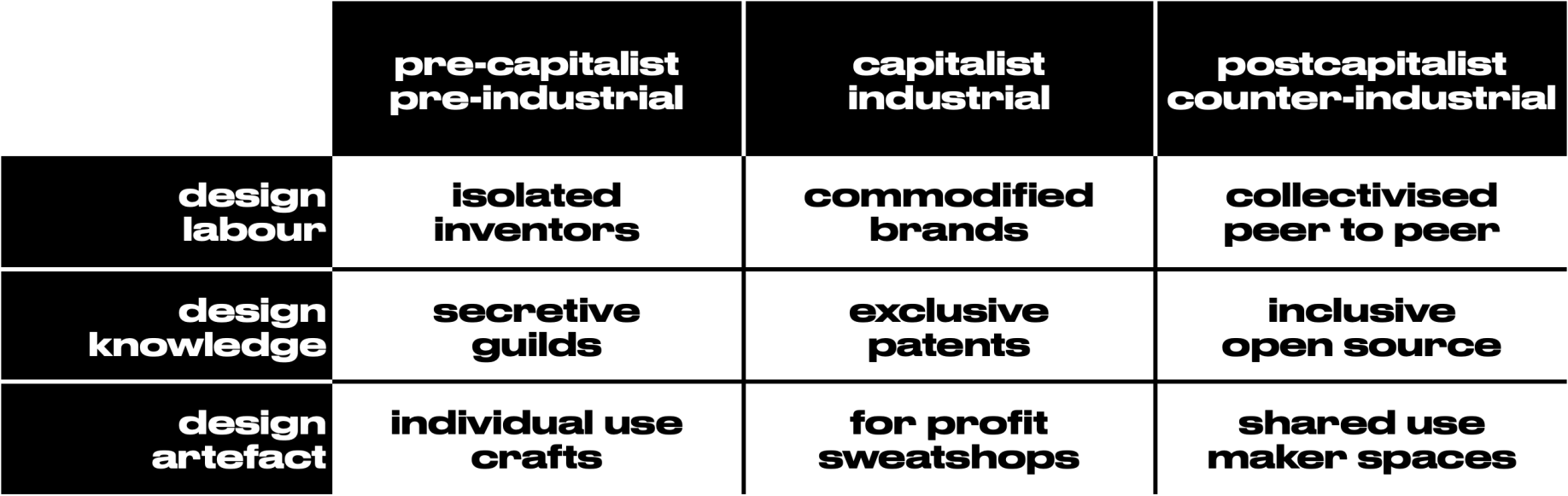

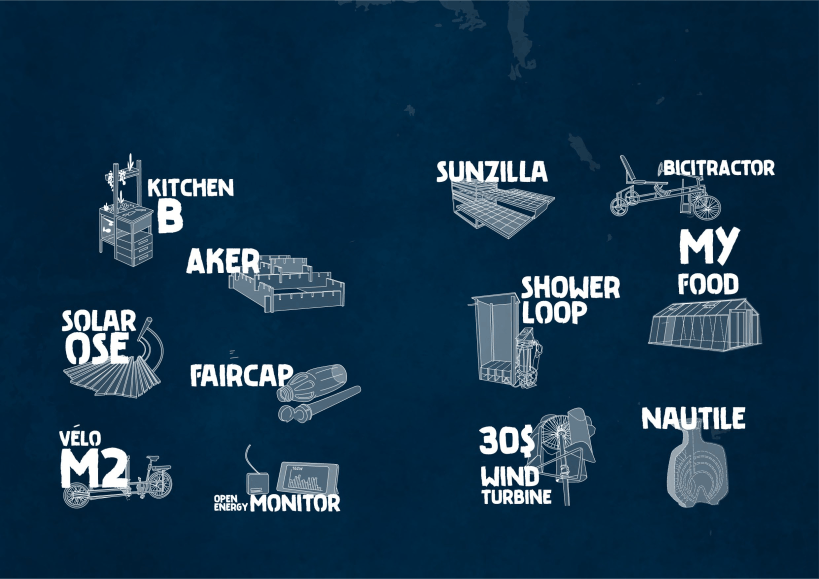

Table 4. Major paradigm shifts in design

In this study, I have explored how design practices can contribute to a postcapitalist transition. Just as the transition into capitalism was a gradual, complex, and uneven process, the way out of capitalism also proceeds by “strange and circuitous routes”. This complexity notwithstanding, it is possible to espy some similarities and differences between these two epochal shifts from the vantage point of my threefold design analysis. To me, the early-industrial inventor is an archetypical figure of design labour. The inventor combines creativity, experimentation, and innovation, and is marked by their isolation from their peers. Under the commodity-machine, design labour has been subordinated to capitalist interests and is increasingly enlisted in the service of late-capitalist global brands. The ways in which design knowledge is treated have undergone a similar process. If once pre-capitalist guilds guarded trade secrets to protect their members’ interests, today the legal framework of intellectual property is reinforced in parallel with tech and media monopolies. Finally, whereas artisanal crafts were meant to respond to individual needs, sweatshop workers toil for no other reason than that of generating profit for multinationals.

With this, we arrive at a triple dead end. Postcapitalist design strives to overcome the impasse by way of commoning. In this context, commoning entails (re)valorising collaborative design processes, facilitating the circulation of blueprints, and rendering local productive infrastructure accessible to anyone. The counter-industrial paradigm, like the periods preceding it, exhibits a degree of internal coherence and self-reinforcement. Accordingly, I have been able to recapitulate correspondences and diverges among key aspects of design cultures in different eras in the following table:

Table 4. Major paradigm shifts in design

In substantiating this shift in design cultures, I argued in the first chapter that the commodity-machine faces multiple crises and that greenwashing has essentially become the general condition of contemporary sustainable design. Although products are endowed with supposedly future-proof qualities, right down to their minute details, the overall objectives, priorities, and urgency of sustainability are lost in the process. Piecemeal attempts to address unsustainability result in manufacturers attending myopically to products’ technical performance or the “footprint” of their production cycle. In focusing narrowly on material performance (often in tandem with misleading aesthetic presentation), predominant sustainable design principles do not respond adequately to the severity of the crises at hand. As such, they disregard the social and economic dynamics that determine how and why these products are made in the first place.

Based on this critique, I concluded that sustainable design must involve more than focusing on the material impacts of products alone. Indeed, confronting unsustainability means recognising that products’ materiality is entangled with the unsustainable social relations of the commodity-machine. The upshot of this is that it is only possible to address the unsustainability of artefacts by redesigning the social and economic relations that condition them. Design in itself, in other words, is neither the problem nor solution. Problems and solutions are to be found instead in the social relations that govern design practices. If reconfigured according to commoning principles, design can contribute towards a postcapitalist transition.

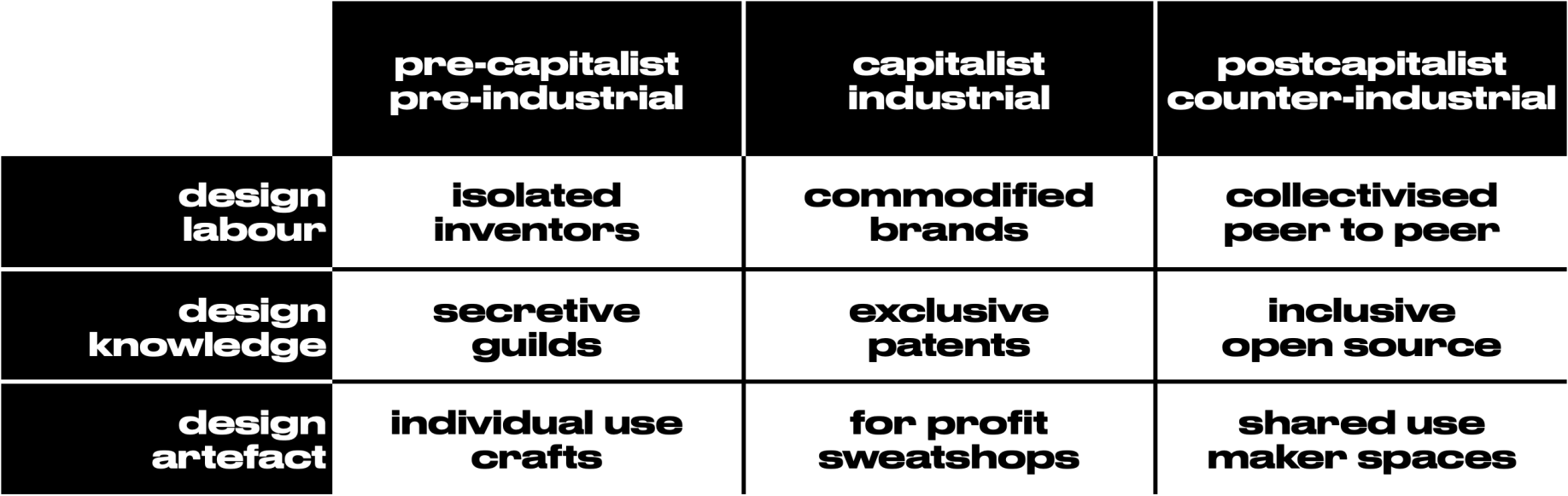

These insights led me to focus on contemporary design projects that practice commoning and stand out as potentially being early pioneers of postcapitalist design. I have attended closely to everyday tools, building systems, and fabrication machinery that are emblematic of peer production, open-sourcing, and the maker movement. Although commoning covers a vast and complex field of collaborative practices and collective action, I have identified three main ways in which it manifests in design. First, designers practice shared creation by working in common and identifying as designer-commoner subjects. Second, open blueprints are held in common in platforms that allow shared governance, clearing the way for the institution of universal design libraries. Third, makers seek shared access to the means of production to allow the provision of “everything for everyone”. Just as market valorisation reproduces itself in and through the commodity-machine, these combined commoning practices also produce and expand themselves through their own momentum. Across the case studies analysed in this study, commoning in design creates shared value, upholds institutional arrangements, and provide a simple abundance of sustainable goods. In negotiating creative work and political action, the case studies also display a productive tension between speculative discourses and prefigurative practices. Together they constitute an ecology of subjectivities, practices, and discourses that can be summarised in this table:

Table 5. Synthesis of postcapitalist design practices

In the second chapter, I introduced collaborative practices that are nothing less than transformative for those who design, fabricate, and use the products in question. Boundaries among these subjectivities dissolve as users become makers, makers become designers, and designers become facilitators. Most importantly, all of those engaged in design become commoners, who produce, reproduce, govern, and replicate shared design projects. Commoners all across the production chain of postcapitalist design generate shared value, which not only benefits the parties involved but also physically realises an alternative value system. Peer designing comes into play in collaborations among designer-commoners not only at the design stage but throughout the value chain. Whereas WikiHouse and Open Source Ecology require massively distributed collaborative principles, OpenDesk and Precious Plastic provide platforms through which individual designers and makers can participate in fair business practices. By establishing institutions and communities of collective action based on free association, peer designers can become more resilient. What is more, they have a better chance of securing their livelihoods and socialising their design labour than they otherwise might if they remain in loose networks of peer-designers. The organisational and business models of such communities prefigure postcapitalist relations while still being strategically integrated into market practices. In designing processes of commoning around a product, these projects become points of convergence around shared political goals.

In the third chapter I investigated open blueprints, the cornerstone of postcapitalist design practices. Although all of the case studies featured in the study make their blueprints available through commons-based licenses, these are of varying levels of sophistication. Whereas some projects have simply uploaded drawings, others present detailed knowledge and provide documentation on sourcing materials, instructions for processing them, source code for electronic components, bill of materials, assembly guides, and forums for troubleshooting. The work is not over when blueprints are made available online. Encouraging diffusion and replication, coordinating improvements and support, and facilitating derivatives and adaptations all constitute essential aspects of commoning, in the sense of shared governance over design knowledge. This, in turn, requires institutional arrangements that can guarantee quality and continuity in open-source projects, as well as keep the process inclusive and accountable. Whereas OpenDesk, WikiHouse, and Precious Plastic showcase successful approaches to documentation and community-building, OpenStructures (and its derivatives) and Open Source Ecology appear to have experienced more difficulties in commoning knowledge. There may be no silver bullet for viral replication, but projects that focus on single, complete products achieve more as compared with vast open-ended systems.

The final chapter combines these insights with strategies for delivering eco-social technologies on which many postcapitalist design practices depend. These strategies all subscribe to low-tech or appropriate-tech ethics with small material and energetic footprints. In enabling hacking by design, they invite DIY cultures and maker movements to repair, customise, or reconfigure the products freely. The end products are seldom consumer goods but tools for a community: maker machines that themselves constitute infrastructure for localised fabrication. Whereas Precious Plastic and Open Source Ecology capture the essence of this means of production, I would suggest that OpenStructures household items, OpenDesk furniture, and WikiHouse constructions also contribute to basic infrastructure. These approaches are in line with a counter-industrial project of decentralising and autonomously generating means of production. That said, none of the projects is strictly autonomous in relation to existing industrial infrastructure in that they rely on preexisting machines, components, and supply chains. Beyond constituting absolute limits, these challenges indicate some directions for further initiatives to take. Given that the counter-industrial paradigm shift is still far from complete, postcapitalist design practices recognise that projects cannot be 100% circular while they remain dependent on the commodity-machine. Instead of fetishising meticulously sourced raw materials only to churn out green commodities, they seek sustainable social relations so as to build fair, resilient, and thriving communities.

Throughout this study, I have analysed how commoning takes place in design practices. Commoning democratises design, not because everybody magically becomes a designer overnight, but because it generates livelihoods for makers everywhere. Commoning enables people to produce quality goods and fair jobs, and participate in localising, improving, and adapting products to suit an enormous array of needs, possibilities, and desires. This conclusion remains descriptive, though, in that it does not tease out the potentials latent in these practices. Each of the case studies that I have presented is unique, displaying distinct strengths and weaknesses. OpenStructures encourages new ways of working for designer-commoners and proposes a platform for everything. That said, its derivatives remain modest and have struggled to make a lasting impact. OpenDesk may pursue smaller aims, but delivers exactly what it promises: a cosmo-local model for flatpack furniture making. WikiHouse, in contrast, does not hesitate to engage in wide-ranging speculation. In this way, it has laid the foundations for a complex endeavour that can only disrupt existing housing practices over the long term. Although Open Source Ecology’s harbours spectacular ambitions, it lacks any structure through which it might realise them in any meaningful way. Finally, Precious Plastic strikes a fine balance in that it encourages the building of machines and communities alike. Each iteration of its products narrows the gap between speculation and prefiguration, between daily practice and grand design.

Several years after they were launched, many of the case studies remain active in one way or another. OpenStructures has significantly overhauled its website, which now gives prominence to recent applications; OpenDesk has fully reviewed and updated their Terms of Service to allow makers more autonomy; WikiHouse had a large-scale application in Hackney, housing 1’000 m2 of low-cost studios for local creative businesses; and Precious Plastic has launched its version 4.0, which includes semi-industrial machines, tools to set up recycling businesses, and an extensive community platform. The continued viability of these projects has inspired countless similar initiatives, ranging from beehives and washing machines to prostheses and firearms. However, questions might be raised about the future impact of even Precious Plastic, arguably the most compelling project featured in this study. Considered in isolation, this clutch of loosely-related case studies might be deemed niche, quirky, or insular. Do these projects merit the label of “postcapitalist”, ambiguous and controversial though it may be? What would it take to connect up this nascent archipelago of practices and make it truly disruptive and counter-hegemonic? Attending to one final project will help synthesise my findings and conclude this study.

In late summer 2015, two collectives from Berlin and Paris (Open State and OuiShare) hosted POC21, which they described as an innovation camp for “eco-hacking the future” (POC21, Home), in Château de Millemont, some fifty kilometres outside of Paris [fig. 34]. For five weeks, more than a hundred “makers, designers, engineers, scientists and geeks” (POC21, Home) gathered on the sixteenth-century estate, where they co-designed and open-sourced disruptive and appropriate technologies. An early announcement described the camp’s political and ecological context and ambitions in stark terms:

POC21 sets itself apart through its explicitly critical stance towards mainstream environmentalism (signing petitions), ethical consumerism (eating organic food), false solutions (recycling), and green capitalism (hybrid cars). What is more, it connects the dots between political, financial, ecological, and mental breakdowns. More remarkably still, the diagnosis extends to the inability to develop “a clear blueprint for the future” on the part of political leadership and social movements alike. POC21 understands this disconnect between resistance and alternatives as stemming from an absence of design in (climate) politics. Instead of negotiations and protests, POC21 proposes a prototype, “a proof of concept that the future we need can be built with our own hands” (POC21, Proof). Inverting COP21 (the acronym for the 2015 Conference of the Parties, widely known as the Paris climate summit), POC21 presents itself as the opposite of diplomatic talks and claims to “move from talking to building a better tomorrow” (POC21, World). Given the pressing timeline of climate breakdown, this preference for deeds over words is more appropriate than promises about distant sustainable futures that neglect the present.

To appraise the significance of POC21, the term “proof of concept” must be seen as more than a witty branding exercise. Broadly speaking, a prototype signifies all of the early forms of a product from which improved and definitive versions may derive. A proof of concept denotes a more specific stage in a product’s development: it involves a focused experiment aimed at testing assumptions. A proof of concept marks the transition from a project’s conceptual, theoretical, or speculative phase to its first iteration. Although incomplete, this first attempt at realising the concept demonstrates—indeed “proves”—its feasibility in the real world. Put differently, a proof of concept is simultaneously prefigurative and speculative: negotiating between the possible and the necessary, it pushes a project to the next stage. In this light, this study can also be considered a proof of concept. By extrapolating the logic of each disparate initiative and connecting the dots among them, I was able to tease out a blueprint for an ecological and social transformation of the economy that involves moving away from market relations and towards socialised ones, from exchange to sharing.

Much as I am interested in disentangling the commodity-machine, POC21 also places great emphasis on “maximum diffusion” and “mainstreaming” in various statements. It aims to achieve the widespread adoption of products that are “sexy like Apple but open like Wikipedia” (POC21, Vision). This provocative juxtaposition suggests that it is not only desirable, but essential to synthesise user-friendly technologies and open-source collaboration. In another succinct expression of its hypothesis, POC21 foregrounds “the disruptive impact that collaborative production, open-source and the maker movement can have on mainstreaming the means of sustainable living” (POC21, Vision). It is striking how closely the three disruptive ingredients listed here overlap with my threefold commoning framework. Similarly, POC21’s plans to “prototype the fossil free, zero waste society” and “overcome the destructive consumer culture and make open-source, sustainable products the new normal” (POC21, Home). The ambitions can be paraphrased used terms established in this study: the goal is “to prototype postcapitalist society, overcome the destructive commodity-machine, and make commoning products the new normal”. It would seem that lessons drawn from POC21 are also applicable to this study, and vice versa.

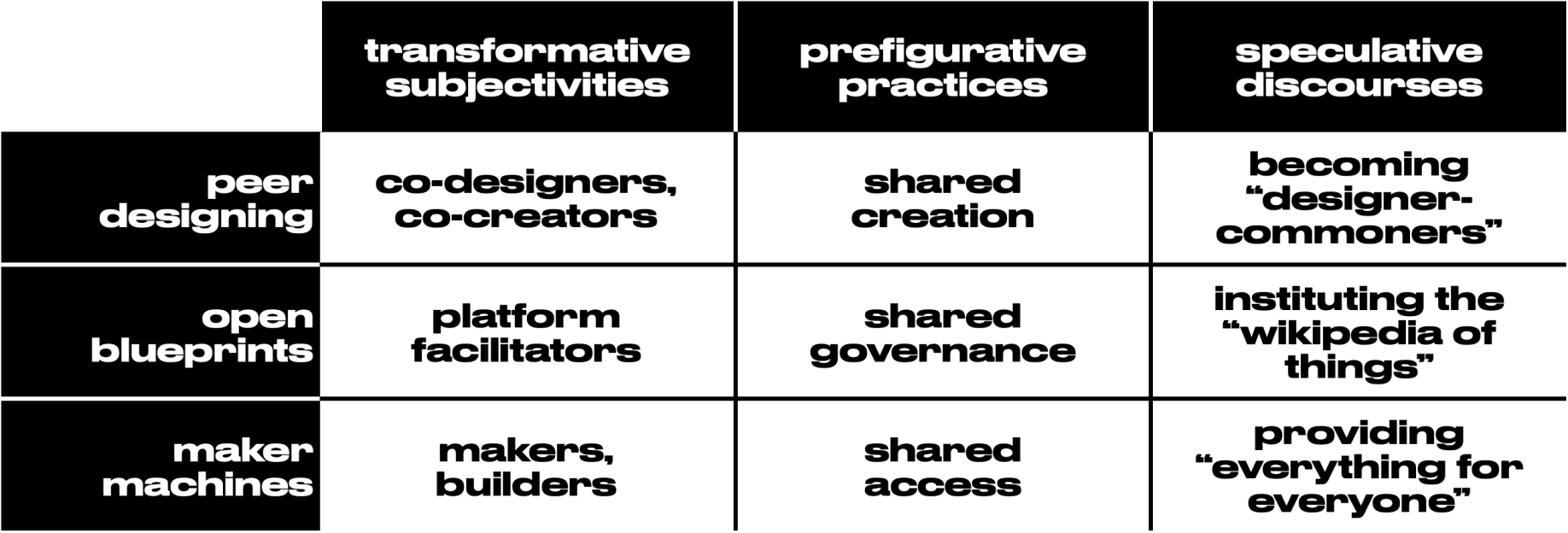

POC21 professes “to build the tools we need for the world we want” (POC21, Proof). That world certainly requires more tools than can be developed in five weeks. They initially received two hundred applications for projects at various stages of development, encompassing “the areas of energy, housing, food, mobility, communications and circular economy” (POC21, Vision). The twelve projects chosen as part of POC21 were divided into four categories. [fig. 35] “Energy For All” covered domestic, urban, and rural applications. There was a portable solar-powered generator for remote locations, energy efficiency monitoring system, and cargo bike that generates energy through pedalling. “Design for Sustainable Living” grouped water-related technologies. This category featured a 3D-printed antibacterial water filtering cap for bottles, biomimetic hot water kettle, and energy-saving, self-filtering, circular shower. “Open-source for Autonomy” focused on off-the-grid solutions, namely a solar concentrator for thermal energy, low-tech pedal-powered farming machine, and $30 Wind Turbine made from reclaimed material. Finally, “Reclaim Food Production” presented food-centric systems. There were snap-fit kits for urban agriculture, an automated permaculture and aquaponics greenhouse, and an integrated kitchen with fridge substitute, composting, and herb garden. Some significant categories were missing from this selection, such as transport, shelter, and communications. Nevertheless, the organisers’ did not aim to provide a comprehensive package of products (unlike Open Source Ecology, they avoided that pitfall). Instead, their curatorial approach meant to encourage cross-pollination among design experiments.

In the following passage, POC21 describes the qualities that they sought out in selecting and developing these products. These come remarkably close to the characteristics of my case studies:

Such a strong speculative vision would be far-fetched if not it was not put into practice in the present. This is why the innovation camp itself was designed in the most prefigurative way possible. Dubbed “proof of living” (POC21, Report 81) and the “13th project” (91), the event functioned as a “hybrid between a festival and the maintenance of a small village” (79). Decisions were taken collectively and responsibilities were shared among all of the participants. These prefigurative practices extended to material flows: fresh produce was grown nearby, consumables were chosen for zero waste, and the workspaces were equipped with OpenDesk furniture. Finally, the event’s timeline and budget were documented, along with the lessons learned. In this way, organisers of future POCs could draw on participants’ experiences.

To facilitate the dissemination of this knowledge, the whole experience was condensed in a report, a documentary, and two exhibitions. The first exhibition, which served as the camp’s grand finale, took place in a large wooden geodesic dome built for the occasion [fig. 36]. The second exhibition coincided with the COP21 climate summit in Paris. It was hosted in the same venue in which thousands of climate justice activists had converged. For a fleeting moment, designers and activists shared a physical space. Nevertheless, the two groups’ practices could have been more closely interwoven. The task of finding mutually reinforcing common ground between growing resistance and creating alternatives continues to confronting designers and activists alike.

Beyond distinct products, camps, and exhibitions, POC21 was a meta-project in which a number of practices converged. It was a milestone event that marked an evolution from individual prototypes towards designing an integrated proof of concept. Postcapitalist design gave way to designing postcapitalism. In this sense, POC21 intends to design nothing short of a vast societal project, an entire way of life. These ambitions are explicitly articulated in its central design objective, namely to build “the most functional and replicable cell of a sustainable society” (POC21, Vision). Since I consider commoning the cell-form of postcapitalism, promoting its replicability represents a sound strategy for the eco-social transition. POC21 provides an exceptionally clear description of this transition:

Redesigning the entire infrastructure of energy, food, goods, and housing remains a daunting logistical task, which POC21 does not mean to carry out alone. This transition can only be designed successfully if the principles of collaboration, openness, and accessibility displace the commodity-machine’s culture of competition, secrecy, and exclusivity. Given the scale of the task at hand, design’s latent political potential appears to be much the same as that of any other social practice: designers can contribute to prefigurative activities that produce shared value—in short, they can engage in commoning. Becoming commoners incites designers, makers, and users to take creative, productive, and collective action. It empowers communities to address the world's greatest challenges “in the shortest possible time, with spontaneous cooperation and without ecological damage or disadvantage of anyone” (Fuller qtd. in Sieden 51).

If a designed world transmits and organises power relations, then recognising design’s potential for commoning opens up a broad range of possibilities for organising the postcapitalist transition. Nevertheless, postcapitalist design is not a silver bullet that can fix everything. Commoning practices may expand organically by reinforcing and replicating themselves, but they do not systematically replace commodified relations with socialised ones. Postcapitalist design cannot disrupt the commodity-machine or bring about a rapid and comprehensive transformation on its own. Just as designers are to participate in postcapitalist politics, organisations and institutions that lead the postcapitalist transition need to embrace designers, makers, and hackers as constituents in their broader movement. Postcapitalist design can be seen as one front in the struggle for the eco-social transition among many. Ultimately, its impact depends on the energy and resources of the social movements that support and sustain it. Other struggles for a postcapitalist transition include defending and regenerating (land-based) commons against resource extractivism; expanding and valorising social services and reproductive care work; and abolishing intellectual property regimes and publicly funding innovation. Recent debates propose a combination of postcapitalist demands, such as introducing a shorter work week, an Unconditional Basic Income and a Green New Deal. These policies could be legislated for “from above” so as to supercharge ad hoc, organic efforts “from below”.

Just as design (in the larger sense, including engineering and planning) was a potent—albeit controversial—component of previous industrial revolutions, so it can be central in the counter-industrial revolution. A peer-producing, open-source, maker-driven, cosmo-local, counter-industrial, postcapitalist mode of production entails a particular way of organising technology, logistics, and social relations. This new organising logic would be compatible with ecological imperatives and indeed contribute towards fulfilling them. A postcapitalist mode of production would have to uncouple manufacturing from industries, set just deindustrialisation in motion, undertake massive ecological remediation efforts, and yet still be able to "make the world work for 100% of humanity". This is no small challenge, but it must be overcome if a rapid postcapitalist transition and, by extension, a fair, sustainable basis for civilisation are to be accomplished. If given enough space and support to flourish, these newly open, distributed, and collaborative principles can surpass the closed, centralised, and competitive systems of the old world. Only then can capitalism’s sophisticated scarcity (and disastrous abundance) be replaced with a simple abundance. "We are called to be architects of the future," Fuller proclaims, "not its victims." That future urges us to reconcile design with politics, resistance with alternatives, speculation with prefiguration, and technology with ecology. An intentional and just Anthropocene is calling us —

Table 6. cycles of commoning in design

Mobirise web page software - Find out