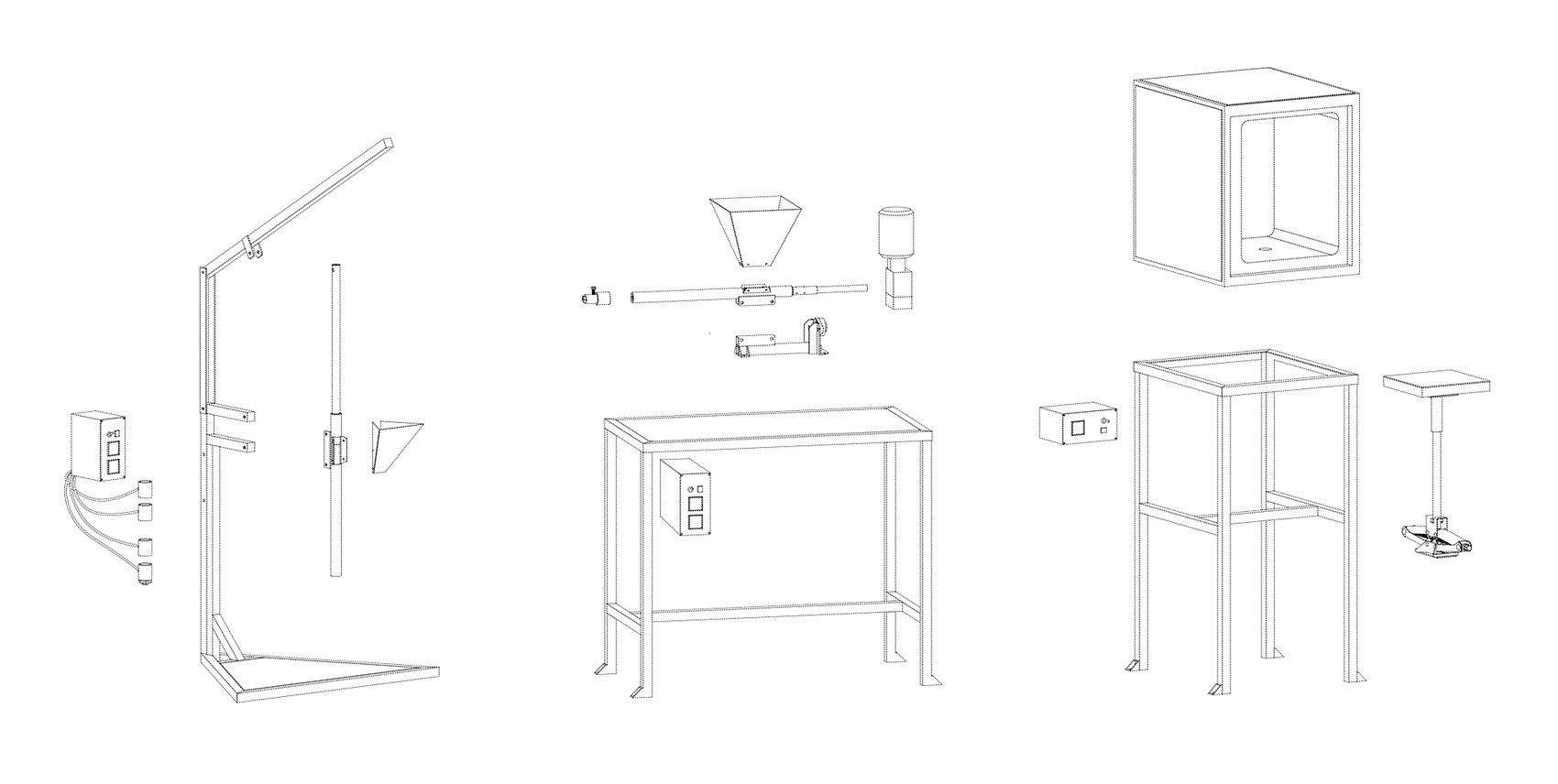

Fig. 27. Overview of Precious Plastic v2.0 creations

To provide some context to the perceived opposition between ecology and technology, I open this section with a closer look at an essay by Ayn Rand. As one of the leading ideologues of neoliberalism, the objectivist philosopher provides an emblematic expression (if not the main contemporary origin) of discourses that pit the eco- and the techno- against each other. Written in 1971 at the peak of the environmental movement, “The Anti-Industrial Revolution” encapsulates Rand’s dismissive as well as terrified attitude towards the New Left in general, and environmentalism in particular.[1] The essay opens with a fictional account of a successful anti-industrial revolution in the 1970s. A bleak regime of eco-austerity (imposed by the government) has taken all everyday modern comforts away from the average Americans: no electric home appliances or entertainment devices; no private automobiles or shopping malls; no plastic bags, diapers or cosmetics; no canned or frozen foods. This speculative introduction allows Rand to illustrate her hyperbolic argument that only an unrestrained technological free enterprise can provide abundance, and that regulating industries will inevitably return civilisation to a state of savagery. The essay pursues at full steam its crusade against environmentalism with uncannily familiar arguments, deeply engrained in Western exceptionalism and colonial thinking. Just to name a few, Rand compares the land area covered by industries to the vastness of “untouched wilderness”, discounts indigenous rights in the name of progress, and perhaps most disturbingly, presents one of the earliest examples of climate denialism. The essay reaches its crescendo with a remarkably unapologetic celebration of air pollution: “anyone over 30 years of age today, give a silent ‘Thank you’ to the nearest, grimiest, sootiest smokestacks you can find” (138).

Rand puts great effort into not only conflating environmentalism with technophobia, but also equating technological progress with free enterprise: “Make no mistake about it: it is technology and progress that the nature-lovers are out to destroy” (138). She then goes further to declare in a conspiratory tone that “the immediate goal is obvious: the destruction of the remnants of capitalism in today’s mixed economy, and the establishment of a global dictatorship” (140). By introducing such equivalences, Rand conveniently draws a line dividing socialism, ecology, scarcity and despotism on one side, and capitalism, technology, abundance and freedom on the other. These associations enable her to spell out the core ideological narrative of the essay: “that collectivism is an industrial and technological failure; that collectivism cannot produce” (140). In other words, collectivism (here understood as a conveniently broad container for any non-capitalist regime, including but not limited to, traditional communalism, a centrally planned economy, commons-based peer production) cannot “deliver the goods” and is likely to end up in disaster. Rand states with absolute confidence that capitalism “is the only political system capable of producing abundance” (141). While she admits that there may be some local instances of actual pollution, she reassures her readers that pollution “is a scientific, technological problem —not a political one— and it can be solved only by technology” (142). While all the previous claims may appear as Cold War oddities, this final argument has not only managed to stand the test of time, but has become the central doctrine in the post-political management of environmental affairs and the erasure of ecological conflicts.

Beyond her rhetorical exaggerations and conflations, Rand deserves credit for accurately describing some of the characteristic environmentalist discourses of the New Left. She observes that “instead of their old promises that collectivism would create universal abundance and their denunciations of capitalism for creating poverty, they are now denouncing capitalism for creating abundance. Instead of promising comfort and security for everyone, they are now denouncing people for being comfortable and secure” (141). Indeed, there is a stark contrast between the optimistic early socialist promises of “heaven on earth” and the bleak predictions of the Limits to Growth, published a year after Rand’s essay (Meadows et al.). Rand and her neoliberal followers benefited considerably from the simple and irresistibly attractive promise of infinite economic growth, and in this light, the ecomodernists appear as direct descendants of Randian ideology. In contrast, arguing to “leave well enough alone” (as Rand beseeches multiple times in the essay) remains a “hard to sell” political project, a problem that persists in the imprecise (if not misleading) naming of “degrowth” itself (Carson, Degrowthers & Ecomodernists). Part of the challenge lies in the difficulty in formulating an alternative and equally compelling use of technology without capitalist mediation, which is bound to remain speculative unless the conditions are created for its realisation.

But what is so special about the capitalist use of technology that it ambiguously generates both a sophisticated scarcity and disastrous abundance? Conversely, what is so inherently wrong with seeking a simple abundance of “everything for everyone”? These interrogations have recently triggered a new wave of engagement with techno-utopianism in the left, imagining radical politics that put technological advances into the service of social progress[2]. Extrapolating the current possibilities towards the desired outcomes, left-accelerationists suggest that a post-scarcity future is both desirable and achievable. The promise of “fully automated luxury communism” (Bastani) may not be a spectre haunting the world yet, but it has certainly established a viral status and attracted academic debate in recent years. At first sight, the term comes across as an oxymoron: surely, luxury is synonymous with exclusivity and commodification, while communism is meant to stand for the exact opposite? For those who inherited the Randian ideology that “collectivism cannot produce”, an egalitarian and abundant future would appear to be a nostalgic throwback to an earlier age with somewhat naive expectations. To counter these reflexes, Mark Fisher reinterprets the term Luxury Communism (the theme of the 2016 Digital Bauhaus Summit) as “Designer Communism”, arguing that while both “luxury” and “design” are concepts that are captured by capitalist imagination, coupling them with communism implies putting the sophistication of design in the service of a universal, shared basis of production. This is similar to what Mike Davis calls “public affluence” (43), being an abundance of shared goods, spaces and infrastructures, rather than the private affluence of the few and the public poverty of the many.

What distinguishes luxury communists from Randian ecomodernists is their critique of capitalist automation, which makes them potentially compatible with ecological thought. Contrary to the popular (yet unfounded) belief, technological unemployment does not advance indiscriminately, nor does it prioritise replacing dirty, dangerous or degrading jobs (Greenfield, chap.7); it is in fact selectively applied according to capitalist interests. Machines may require high upfront costs and some subsequent maintenance, but they never call in sick, they don’t unionise to negotiate better conditions, and most importantly, they never go on strike. Simply put, mechanisation eliminates troublesome workers, not the troublesome work as such. That said, rather than the reliability of machines, economic factors are even more influential in determining which jobs are to be sacrificed to mechanisation. It is more profitable to invest in machines that eliminate high-skilled, specialised and well-paid jobs, while there is little incentive for the capitalist to replace low-skilled, replaceable and poorly paid workers with sophisticated machinery. The interests of workers are rarely on the table where decisions are taken, designs commissioned or investments made, which is why the most dreaded activities (whether they are tedious, dangerous or meaningless) have not disappeared over centuries of mechanisation. This critique results in the following observations: first, the ever-increasing productivity under industrial capitalism has failed (or rather, didn’t even try) to deliver humanity from work; in fact it has become more precarious and less fulfilling than ever (Graeber, 'Of Flying Cars'). Second, the working week and/or retirement age have not decreased any further in the post-war period; and, even free time is becoming colonised by work with the advent of instant communication (Crary). Third, with current rampant unemployment, chronic underemployment and precarious employment, the idea of full employment seems to be an unworkable (if not delusional) undertaking (Srnicek and Williams chap.5).

Combining these observations, luxury communists ask an entirely different set of questions to those Ayn Rand’s would-be anti-industrialists would be expected to ask. If technological unemployment is a given, how can it be beneficial to anything other than capital? What happens to automation when capitalism is taken out of the equation? For luxury communists, the political demand to improve employment conditions needs to be superseded by the demand to infuse automation with an emancipatory purpose: abandoning employment altogether and establishing an intentional, quantitative reduction of work time. While the emphasis on “full” automation could be understood as entirely autonomous robots requiring no human intervention, it is meant more as the opposite of “full” employment, implying a desire to advance towards a society where most (if not all) work is automated and wage labour is eradicated altogether. Luxury communists build upon the legacy of the undercurrent of the anti-work ethic that runs through radical thought, from William Morris and Paul Lafargue to the situationists and autonomists (Black; Frayne), and follow more closely the post-work politics of André Gorz (Paths; Reclaiming). Distinctively, luxury communists profess a greater appreciation of cybernetics and planning than their predecessors. Confirming Rand’s worst nightmares, they do not shy away from expressing the need to reign over the “commanding heights of the economy” —and to build power accordingly.

If the hyperbolic discourse of fully automated luxury communism is meant to provoke thought and imagination, it may be both well-meaning and strategically effective. However, it needs to be seriously nuanced and confronted with environmental considerations, which often appear as an afterthought to techno-utopianism. It would be unfair to deny that electronics and computing are extremely resource- and energy-intensive, particularly due to their dependence on the extraction of rare earth minerals with heavy environmental consequences (Vansintjan). Without acknowledging and factoring in ecological limits, speculating on a high-tech future without empirical evidence is at best a false promise, and at worst a neo-extractivist project that is not so different to eco-modernism. Similarly, the simplistic demands of “full” automation also fail to recognise what forms of labour will be indispensable within an ecological transition, and would therefore need to be valorised. Consider some of the tasks at hand: installing renewable energy infrastructure, retrofitting the built environment (to withstand or adapt to the impacts of climate), feeding the world population (with small-scale sustainable agriculture), expanding education and health services, remediating pollution, salvaging waste and regenerating resilient ecosystems, to name but a few. All require human labour at its best: working with care, creativity and collaboration. Technologies can facilitate and empower these daunting tasks immensely, can remove the burden from workers and reduce the necessary work time, without devalorising human intervention. It is, however, very likely that some of these activities are better left non-automated, as human labour can be less energy-intensive than sophisticated machinery doing the same or equivalent tasks.

Beyond primitivist rejection and superfluous application, it is possible to combine some of the compatible elements of degrowth and accelerationist positions. Such a counter-industrial paradigm can critically endorse automation, and negotiate its socially and ecologically beneficial reorientation. Instead of uncritically declaring that automation spells the end of work, it is possible to conceive intentional, selective automation while recognising that there will be plenty of valuable work to do for generations to come. This would not be governed by what capital deems fit, but would instead follow what liberated workers find desirable, hence the need to specify what the transitory forms of work may look like, and how they can be complemented with machines. Repurposing William Morris’ distinction between two kinds of labour, an intentional application of automation that destroys strictly “useless toil” while encouraging and enabling “useful work” can shift work away from its alienated, precarious and extractivist forms. Intentionally counter-industrial automation may turn the destruction of jobs into an opportunity to liberate time for creative work (Thompson). With this perspective in mind, it is now possible to look at present-day practices that rely on machines to empower makers. While the aim may not be full automation, the following case study provides a glimpse of how even existing technologies can be repurposed in a humane, socialised, communal ways.

[1] All quotes in this section are from Ayn Rand, "The Anti-Industrial Revolution" (alternatively called "The Return of the Primitive")

[2] I have previously cited several authors (Bauwens; Fisher; Mason; Srnicek and Williams), but the broader debate includes enthusiastic endorsements (Bregman; Frase), critical engagements (Greenfield; Noys) and polemical provocations (Sharzer; Phillips).

A gallery of colourful plastic objects are on display: a spinning top, various plates and flower pots, hand-woven hats and lampshades, clipboards and 3D printer filaments. [fig. 27] They could belong to any fashionable gift shop, filled with endless plastic junk, far detached from self-proclaimed world-saving design projects that are of interest to this research. After all, up-cycling single-serving plastic bottles, bags or cups were the first reflex of sustainable design, and such objects are once again conceived as consumer goods, mainly for decorative purposes, with limited usefulness and therefore of rather insignificant value. Crucially, these approaches have little to no effect on plastic pollution, since they piggyback industrial processes without challenging their ever-growing and accelerating rate of extraction and consumption. Focusing on recycling rather than reduction strategies remains a palliative effort at best, and a distraction at worst. To make things worse, recycling rates are not at all satisfactory, as less than 10% is looped back into production, and about the same amount is incinerated and ends up in landfill and the oceans (Geyer et al.). There is a technical reason (or rather, excuse) for this low rate: big manufacturers employ highly efficient, sophisticated and expensive industrial machinery with low error thresholds, but these machines require virgin plastic pellets with no imperfections or irregularities, which excludes most recycled plastic. In other words, industries usually lack the time for recycling.

Given this context, the particular set of recycled plastic objects mentioned above are worthy of mention, as they are not really end-products, but rather by-products of the project in question. The showcased creations are made by Precious Plastic machines developed by Dave Hakkens as part of a design project aimed at increasing the rate of plastic recycling, without prescribing in advance what objects ought to be produced. Not unlike the previous case studies, which were more than products (OpenStructures can be seen as a protocol, and OpenDesk as a platform), what sets Precious Plastic apart is its outcome: a set of machines. Instead of designing goods for “end-users”, Hakkens designs machines for “end-makers” – a tool with no frivolous visual appeal, but strictly bare-bones engineering; not a product, but an enabler of production. Precious Plastic is a paradigmatic and perhaps even pathbreaking case, in that it responds to ecological needs with machines. It is nonetheless not an industrial techno-fix, but a community tool that brings makers together. It intervenes in plastic pollution neither by austere nor disciplinary means (as bans and fines usually are), but by enabling a brand new craft and promising a responsible yet luxurious repurposing of plastic waste. As the final sections of this chapter will explore, Precious Plastic is thus the ultimate example of what counter-industrial maker machines are meant to be: a self-produced means of production, and a substitute to the industrial commodity-machine.

A closer look at the designer’s intentions, and the making of the machines and their impact may clarify these claims. Born in 1988, Dave Hakkens studied at the Design Academy in Eindhoven, and received rare exposure in 2013 with Phonebloks – a graduation project that envisioned a modular design for mobile phones. Rather than launching a start-up company and courting investors, he instead approached the potential users of such a hypothetical phone directly in an attempt to perpetuate the idea that such a phone is worth producing. His campaign was an unprecedented viral success, gaining nearly a million supporters and an audience of almost 400 million social media users. Instead of monetising this success, however, he encouraged the community of interested parties to take on the responsibility of looking after the project, turning his attention back to Precious Plastic, his other graduation project, which “was a proof of concept, something that worked as a prototype but was not ready for scaling it up yet” (PP, Micro Recycling). The machines themselves are made with basic tools that are widely available around the world, and the components are kept as simple and accessible as possible, making them affordable in price and easy to build, repair or customise. This makes Precious Plastic especially relevant for developing countries, where industrial facilities are unavailable and low-income trash collectors can only resell plastic in bulk. While this approach remains faithful to the ethics of appropriate technologies, as later experiences demonstrate, assembling machines out of salvaged parts does not necessarily deliver the same quality everywhere in the world.

The first machine is the shredder, for the production of plastic flakes to be fed to the other machines. The blades themselves are meant to be digitally manufactured – cut out of a sheet of steel, while the framework, electronics and hopper are handmade, and the motor is salvaged. The other three machines process the plastic flakes through compression, injection and extrusion. The compressor is the easiest and cheapest machine to build, comprising essentially a reclaimed oven with improved electronics, and a jackscrew to press the melted plastic into a mould (that fits inside the oven). The injection machine melts and injects the plastic into any small mould, producing objects mainly in series. Finally, the extrusion machine, as the most difficult to assemble, comprises a drill rotating inside a heated tube, producing a continuous string of plastic that can be given shape immediately by hand, or used as filaments for 3D printers (still in development). These are unlike the high-tech machines that most people are used to, and are neither superfluous consumer electronics nor the industrial infrastructure that produces them. They are an essential piece of equipment, simplified, and “reverse engineered”. [fig. 28] This methodology is in direct opposition to the proverbial “reinventing the wheel”: rather than a brand-new invention, it is a liberation of already existing technologies away from specialised industries into the hands of makers.

It takes approximately two weeks and costs up to €1000 to build all the machines, depending on the amount of components that are to be salvaged from a scrapyard rather than bought from a hardware store. Some of the electronics are acquired from eBay, and hence not procured locally, but are available from a wide range of suppliers. Intended for the widest circulation and broadest adoption, the machines are designed for self-production, although it is also possible to seek help from more experienced makers. In any case, Precious Plastic does not sell the machines, but encourages other machine builders to do so, without asking for any licensing fee or share of the profits that can be made; all the blueprints, know-how and learnings are shared freely online. The mission to recycle plastic trumps all other considerations, and success is not measured by monetary income, but the replication of machines. The more machines are made, and the more knowledge is acquired about recycling plastic, the more the waste is valorised. What was once an externality (plastic waste, undesired and uncared for) is looped back into a valorisation process. This may paradoxically appear as a palliative solution, as the machines may actually justify sustaining plastic waste rather than eliminating it. In fact, the machines function only as a gateway to community-building, and machine-building becomes the material consolidation of people’s engagement in the recycling of plastic. In a way, the strict separations between design, engineering, manufacturing and consumption collapse, and give way to overlapping ways of making, with machine-making, pellet-making, mould-making, craft-making and community-making all melting into each other.

Hakken’s approach was well received right from the start – he was awarded a Social Design Talent prize and a Keep an Eye grant, both worth €10,000, to take the project forward, and offered to donate the money to someone who could help him improve the designs and launch Precious Plastic v2.0. Once again, he was given back more than he had initially offered – not only did an experienced machine builder join him, but many others offered their help in various aspects of the project, such as web development and logo redesign. The logo captures the irreverent reversal of values, being a white plastic bag, proudly waving on a flagpole – a mundane and worthless object standing in for the heavenly symbolism of a flag [1] [fig. 29]. Less than three years after the original project was launched, the new designs were published in 2016, complete with instructional videos, design blueprints, electronic schematics and bills of quantities. At the time of relaunch, Precious Plastic had by far the most comprehensive project documentation among the case studies herein, as well as a growing, vibrant community. There has been a steady flow of images from every continent, capturing proud makers with their self-built machines and their recycled creations [fig. 30].

Precious Plastic employs the same strategy as Phonebloks for its diffusion, relying on viral online content creation that delivers a rapid outreach to a broad follower base on social media. The website is full of encouragement to spread the good news: “Let people in every corner of the world know they can start their own local plastic workshop”, “We’ve developed machines to recycle plastic, let’s make sure people know they exist!” (PP, Home) However, there would be little motivation to share unless visitors find the project relevant and feasible in the first place. Hence the commitment to open-sourced documentation (appropriately called “blueprints”), which “will always be freely available online, for anyone to access and use”, makes sure the project is reliable enough to initiate long-term engagement. Finally, considerable emphasis is given to how easy it is to produce the machines, “made with basic tooling and materials that should be easily available, wherever you live” (PP, Machines). The simple language, neutral visuals and complete documentation stand as an almost evangelical effort to spread Precious Plastic, through both the reproduction of the designs and the production of the machines. The goal is not simply to have people build the machines in isolation, but to “create a worldwide community of like-minded plastic savers” (PP, Plan). After all, the makers are not customers, but collaborators of Precious Plastic; a forum brings them together to improve the designs, to develop new uses for the machines and to showcase their plastic creations. There is a triple process that Precious Plastic puts in motion: the designer open-sources a machine set, the makers replicate the machines and moulds, and the craftspeople make use of the machines. Of course, these roles are not necessarily separate, but melt into one another, just as the plastic flakes from multiple sources are melted together to take new forms. Pushing that logic further, the ultimate success of the project would be for Hakkens to be only one maker among many within a project that is entirely managed “by the makers, for the makers”. While no project has yet reached that stage, as the focus shifts from the machines to products, the initial work of the designer fades into the background and the makers take the stage.

Wrapping up this first stage of Precious Plastic, a few challenges stand ahead of the project as it expands and matures. There seem to be at least three main factors that will determine its future. The first is to see these machines put to good use in the production of relevant, useful, valuable creations, as this will be the main motivation for the widespread adoption of the machines. If the community develops and shares its own open-sourced moulds, the utility of the machines will keep expanding. The second factor is the level of incentive the machines will generate for the collection and sorting of plastic, or in other words, its actual contribution to “cleaning up the mess”. Precious Plastic wholeheartedly embraces this challenge: “Whether we like it or not, plastic is our inherited toxic legacy. Let’s use it as a resource to create new value and social innovation” (PP, Plan). Crucially, identifying and separating plastic waste remains the most laborious stage, and this cannot be achieved solely by an informal community of “plastic savers”, requiring a much larger social cooperation of multiple actors, associating with households, factories, street collectors, municipalities and junkyards. This is why the value created by Precious Plastic must exceed the strict utility of the creations and create livelihoods across its entire value chain. The last factor for success is the viability of the project’s business model. The website confesses that “we haven’t really figured out a proper way to fund this yet. Our priority is to find a solution to plastic waste, not to create a business” (PP, Donate). It is yet to be seen if the project can be effective in running without a sustainable plan.

[1] Note the distant resemblance with the Pirate Party logo, also a flag on a pole, also shaped like the letter P.

Emboldened by the interest Precious Plastic v2.0 generated, Hakkens and his collaborators moved forward to develop a Version 3 in early 2017, calling for support with two things: money and people. For financial support, they set up a Patreon account, which provides them with a modest but regular income, allowing them to maintain their own livelihoods. Crowdfunding is particularly appropriate for a project with a social mission that navigates between precarity and autonomy, “to make sure we can always stay focussed and move forward without having to do side jobs in the weekend” (PP, Creating). Unlike the corrupting influence of venture capital or start-up acquisitions, crowdfunders do not expect financial return, but rather participate in a gift economy where the reward is staying true to the social purpose. There is, however, only so much money can buy, and attracting talent on a voluntary basis is more valuable than cash. Several designers have joined Hakkens to carry out material experiments and to develop a series of creations that demonstrate various applications for the machines, and these collaborations resulted in a range of finished products (sunglasses, phone cases), works of art (sculptures or jewellery), building materials (bricks, beams, 3D printer filaments) and domestic items (both decorative and functional). These testify that there is more to Precious Plastic than a futile cycle of “garbage in, garbage out” —a closed-loop of recycled junk. To promote this wide range of possibilities, an online “bazaar” has been established, not just for selling finished consumer products, but also for moulds, plastic flakes and machine parts for the makers themselves. Fully aware that a market place does not create a community, greater emphasis is given to the online interactive map on which plastic workshops, machine builders and anyone who would like to get involved in plastic recycling can subscribe and connect with like-minded neighbours. This map gives a sense of how Precious Plastic has already reached every continent, and how much more potential there is to engage the uninitiated.

Version 3 also provides better support for the setting up of new workspaces. The complete workshop covers every stage of production (from waste collection to the showcasing of finished products) inside a generic shipping container, which can be set up on a landfill, a remote beach or a city square [1] [fig. 31]. The documentation estimates €3000 in costs and a month of work to establish one from scratch; such micro-factories require much less investment, expertise and infrastructure than highly sophisticated, centralised and integrated plastic recycling facilities. The project confidently claims that “over 200 plastic recycling workspaces have already been set up and a new one is opening up somewhere around the world every week” (PP, Creating). Having streamlined the process and proven its compatibility with diverse locations and contexts, Precious Plastic presents a concrete counter-industrial model for the transformation of an environmental liability into economic viability. One example of this dual benefit is an initiative launched during the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. Trash collectors from the favelas came together to form a cooperative, to recover plastic waste from the competition venues and to immediately process them in collaboration with Remolda – a mobile recycling factory – to produce souvenir items to be sold to the tourists, as the very source of the waste. The project carried the slogan “plastic is worth gold” and their presentation video discloses the numbers: “Mixed plastic: R$0.90/kg. Separated, crushed and cleaned: R$4.00/kg. Final product: R$15"[2] (Plástico, 2:40-2:48). The profit was returned to the cooperatives to pursue their efforts to clean up Guanabara Bay and the surrounding national parks (Pontes).

The new version also provides more insight into the evolving discourse of the project. Over and above the casual encouragements on the website, Precious Plastic seized the opportunity to launch v3.0 during the 2017 Dutch Design Week and presented a full-fledged manifesto to the public [fig. 32]. Beyond mere statements, the manifesto was accompanied by a series of artefacts: “Five objects crafted with a lot of effort (…) Pushing the limits of plastic recycling. They tell the story about how we value plastic” (PP, Series). The first statement, entitled “Dawn of cheap”, tells an origin story for plastic, explaining that it was initially invented as a cheap and easy replacement to ivory, which was in high demand but scarce and expensive. A plastic replica of a massive elephant tusk accompanies the story, made up of layers of plastic, deposited as if it had grown over the years, with a gradient from raw roots to a smooth tip. While no explicit reference is made to the violence of ivory poaching, the striking presence of a realistic imitation prompts the viewer to consider plastic in a better light, as a (relatively less violent) substitute for the qualities attributed to ivory. The second statement shifts the status of scarcity from ivory onto plastic itself: “Plastic is made from oil – a fossil fuel that took thousands of years to be created. Yet, we trash plastic in a matter of minutes. Once we burn it, is is gone. Forever. (…) It is time to treat this scarce material as a valuable, scarce and finite resource.” This echoes Victor Papanek’s dictum, “That which we throw away, we fail to value” (Papanek 78), indicating that things designed for single use are, by definition, given no value at all. This time the accompanying display is Precious Plastic ingots in multiple colours, stacked like a pyramid of gold bullion. Here, the literal imitation of precious metal is meant to question the illusory abundance and worthlessness of oil derivatives. That said, the gold metaphor implies constant value (as the gold standard used to be), overlooking the unpredictable value fluctuations of oil.

Perhaps the ambiguity of the concurrent overvaluation and undervaluation of plastic is better expressed in the third statement: “Plastic is one of the longest lasting materials on the planet. It does not decompose and will stick around for hundreds of years. Yet we use it to make the cheapest, most disposable products. (…) An incredible waste of potentials” (PP, Series). This is perhaps the key paradox of plastic: discarded as waste, it is abundantly available for free, while creating poverty by damaging ecosystems. By transforming un-precious, unwanted, wasted plastics into valuable, useful and desirable raw material and finished goods, Precious Plastic seeks to eliminate the abundance of waste, putting the discarded plastic into good use, and generating value and livelihoods in the process. The demonstration piece for this statement is a monumental crystalline sculpture weighing 17 kg, cut like a precious stone, freckled in marble-like colours, polished to a high gloss finish. Dubbed an “anthropocenic gem” (PP, Making), it could be a future geological formation deposited over millennia if plastic pollution goes unchecked, and a logical extension of the already-documented “plastiglomerate” plastic-rock composites (Robertson). Alternatively (and on a more optimistic note), this otherworldly monolith testifies to the inherent beauty of the material like no other application, perhaps inviting its admirers to imagine such monuments on every beach that has been cleaned of its plastic waste. This abstract nature of the artefact elevates plastic and celebrates its aesthetic qualities without any symbolic mediation, without resorting to the direct imitation of anything culturally valuable like the previous examples. This piece served the project particularly well when it was displayed in the shop window of a major department store on a major commercial street in Amsterdam. One window was filled with all kinds of plastic trash with the word “PRECIOUS” under it, while in the next window, the object of art sat on a pedestal in front of a white background, subtitled simply “PLASTIC” – a simplified yet effective expression of the paradox for the countless passers-by to reflect upon. [fig. 33]

The last two statements and their corresponding objects relate to the craft, time and effort that makers put in Precious Plastic objects. “We try to push the boundaries of plastic, how it is produced, reproduced, viewed and consumed by society. We like working with plastic in a more human way —on a smaller scale with room for details and love. Like a craftsman” (PP, Series). An imposing vase illustrates this point. Made out of recycled DVD boxes, handcrafted with a textured surface, it stands in stark contrast to the industrially standardised objects that emerge perfectly identical from a single mould. The re-emergence of crafts (Sennett) is often thought of as a return to traditional artisanal techniques, but what Precious Plastic proposes is nothing short of creating a new kind of craft for the 21st century. As a field previously monopolised by industry, being a craftsperson in plastic would be an essential trade similar to working with wood, metal or ceramic, with great expressive potential and economic viability. This economic dimension is discussed in the final statement: “Plastic isn’t cheap by nature —it’s how we, as humans, deal with it. Products are mass-produced in huge quantities to keep prices low with very little care placed on each individual plastic object. That same object could quickly gain value and preciousness by dedicating some extra time and effort to it” (PP, Series). Indeed, Precious Plastic does not really intend to beat the plastic industry in their efficiency; aiming for small-scale production, the goal is to seize a value chain that mass production is unable or unwilling to occupy. The final object captures the contrasting aesthetics of crafts and industries in a single piece: a standard Monobloc white plastic chair, but with intricate lace and cutwork textures. This time it is not the physical properties of the material that gives its value, but the sheer time and effort spent manually transforming it that makes the final object so singular and infinitely more precious than its universally ubiquitous copies, which are estimated to exist in their billions. If the Monobloc (and everything else that is made out of plastic) is here to stay on this planet, better they be treated with more care, and by extension, with the value they deserve.

Some years after building the very first prototype, Hakkens and his team show no sign of stopping, and are working on yet another version. After all, how could one pretend the project had reached its goals? Hakkens admits that “it’s hard to just deny this massive global plastic problem and move on” (PP, Creating). Emboldened by more than 6,000 people from around the world wanting to get started, they announced in summer 2018 plans for “creating an army to fight plastic waste” (PP, Version 4). Military metaphors aside, they have good reason to step up their ambitions, having been granted a vast workshop space in Eindhoven city centre by the city, and even more impressively, they have been awarded €300,000 by a foundation that will be spent entirely on developing v4.0, representing an almost tenfold increase in budget when compared to the previous version. Having operated on a voluntary basis to date, they openly express their resistance to professionalisation: “We could employ six people full time paying normal salaries for a few months. Or we could invite 40+ dedicated people from around the world and cover all the basic expenses (…) We like to think the second option is the most efficient and beneficial for the project” (PP, v4 Plan 11). More than 600 people have applied from around the world to fill 46 well-defined roles that include engineers (to improve the safety, efficiency, washing, sorting and automation of machines), product designers (to explore and create useful and valuable products for the community to reproduce), web developers (to rebuild a community platform to meet, collaborate and share online) and community builders (called “the cherries on the cake”). The latter also includes activists to “develop different strategies or actions that people can peacefully take to push humanity beyond plastic into a new sustainable era away from petrochemical mass suicide” (PP, Version 4).

It is perhaps fitting that precisely when my role as an academic researcher studying Precious Plastic was coming to an end, I was invited to become one of the two in-house activists with responsibility for strategising, mobilising and designing activities and for lobbying politicians. The triple subjectivities I announced in the introduction —as researcher, designer and activist— once again meet and merge in a new configuration. I would admit that the boundaries have remained blurred throughout my investigation: I became friends with the Precious Plastic team, urged them not to name the bazaar a “marketplace” (fearing it would undermine my argument), and even motivated them to join a mass civil disobedience action against coal extraction. They too have embraced their permeable and interchangeable roles, accepting that creating a postcapitalist alternative through design practices alone is not enough, and understanding that political interventions, ecological resistance and civil disobedience are necessary and integral to creating effective and lasting change. In this sense, Precious Plastic is certainly more of a social movement than a design studio, and my involvement has become a more or less conscious attempt to develop a synthetic design/action/research methodology. There may be no other way to engage with a postcapitalist project than to become part of it by breaking disciplinary chains, and uniting as makers without borders.

[1] The first pilot for the integrated workshop was launched in Kisii, Kenya in collaboration with UN-HABITAT, followed by two more pilots; one in Patagonia (led by a women-only crew) and the other in the Maldives.

[2] The souvenir item weights merely 30g, making the added-value several hundred-fold.

How to create your own site - See here