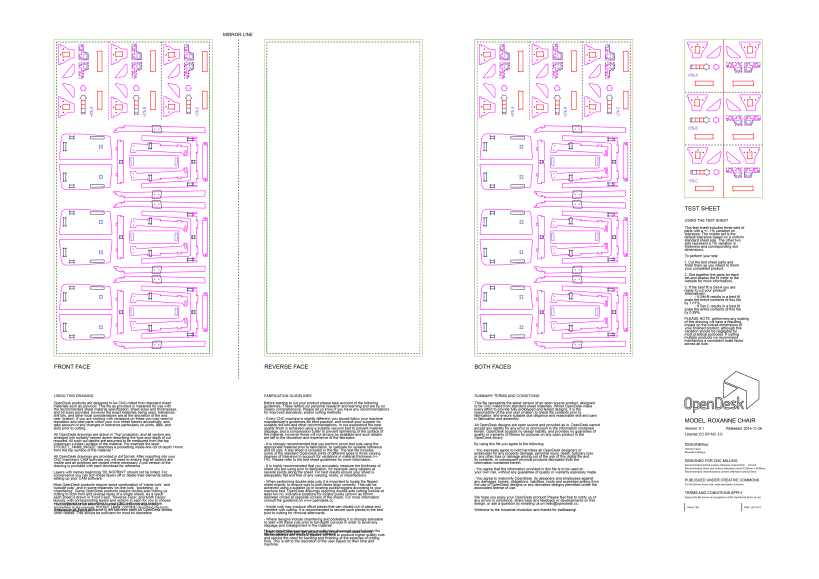

Fig. 11. Promotional shots of Studio Desk by Joni Steiner and Roxanne Chair by Pierrick Faure

I am writing this introduction while sitting on my chair in front of my desk. This self-evident statement warrants taking a moment to interrogate the infrastructure that is necessary for me to engage in my work: a computer, a public library, fibre-optic cables running beneath the Atlantic, and at the most physical level, a chair and a desk. I recall once again André Gorz remarking how we live in a civilisation in which one’s production and consumption are entirely separate spheres of activities. The statement suddenly makes me sit less comfortably on my ergonomically optimised, elaborately cushioned, petrochemical office chair. I realise that I have no connection whatsoever with the production of the artificial environment that surrounds me. From the political-economy angle of this research, I can conclude that I have very little control over the means of production of my research; they are all produced, owned and managed by anonymous others. What if I had been involved in the production of some of my very means of production? Perhaps the chair and the desk would be the easiest ones to begin with, yet also the most consequential ones in terms of the immediate experience. Instead of engaging in the standard consumer experience of buying and assembling some IKEA furniture —designed in Sweden, manufactured in Poland and tax-evaded in the Netherlands— I could choose to commission a carpenter to produce them for me. Alternatively, I could improvise a clumsy bricolage myself, even though I lack the practical skills. The first two would be embedded in exchange relations, whereas the latter would be a solitary demonstration of self-reliance. The options, however, do not end there. As this section will explore, there may be other ways one can make one’s own furniture, in collaboration with others, and yet outside DIY, traditional crafts and the commodity-machine.

OpenDesk promises such a new modality in the form of “Open Making”. Facilitated by the Internet, the core vision of Open Making is to liberate design knowledge by placing design blueprints in free circulation. Relying on digital manufacturing techniques, it also adapts generic, essential products to an entirely different supply chain to production, where land and labour are cheap, requiring shipping long distances to retailers. Using only plywood sheets processed by a CNC machine,[1] OpenDesk proposes a range of office furniture that is “designed everywhere, made here” (OD, Inside) – a critical reversal of the “designed in California, assembled in China” labels on Apple products. The slogan itself hints at the origins of the project. When the designers at Architecture 00 (“Zero Zero”), the London-based collaborative architecture studio, were commissioned in 2011 to develop a consistent interior for both the London and New York offices of a company, the design team faced the challenge of how to produce the same products on both sides of the Atlantic, without having to ship furniture overseas? The solution was best encapsulated in the saying (often attributed to Keynes) that “it is easier to ship recipes than cakes and biscuits”, or in this case, shipping design blueprints instead of objects, to be produced by through digital manufacturing techniques, following the same specifications and standards. Following the principle of “shipping files, not furniture”, since the CNC millers required to produce the furniture are also available elsewhere, the same designs could potentially be produced anywhere. By publishing open design blueprints for generic office furniture, the designers could then reach a considerably larger audience than the specific client that commissioned the designs, connecting three communities in a “global platform for local making” (OD, Open Making). OpenDesk presents its commercial operations as follows:

In this peculiar marketplace, visitors are provided with several options rather than the ubiquitous “buy now!” button that activates credit cards, warehouse stocks and shipping containers. There is strictly no stocked furniture, with everything being produced on demand, reducing excess and waste. It provides links to the nearest maker-spaces registered in the OpenDesk network where one can ask for a quote to get it made, with a royalty fee for the designer and the platform included in the price alongside the production costs. Next to this relatively novel yet still conventionally commercial method, the blueprints are freely available for download, intended for self-made, non-commercial use, defined as “with no intention to gain commercial advantage or monetary compensation” (OD, Non-Commercial). There are several scenarios of non-commercial use imaginable: a DIY enthusiast making their own furniture for home or office, teachers or students producing for educational purposes, or volunteers manufacturing for a non-profit project. As long as the final users do not outsource production to commercial makers, no money changes hands between the maker and the user (other than to acquire the raw materials and to rent the machines). In this scenario, the designer does not charge for the blueprints either, and anyone can benefit from their content, “whilst also attempting to prevent commercial activity falling outside of their control” (OD, Non-Commercial). This non-commercial principle is a model that warrants closer attention, as it opens up a generous space in which commoning opportunities can develop. Finally, if a client needs a customised outfitting of their office instead of generic pieces, it is possible to commission OpenDesk’s design studio directly. In this case, the private commission also serves as a research and development phase for new open design blueprints, thus making the market relation work for the commons. Although presented in the most conventional commercial form, this modality appears to be even more productive of shared value than non-market relations, illustrating hybrid economic forms that exemplify postcapitalist practices.

There are some prominent design considerations that are common to most OpenDesk furniture: an assemblage of pieces nested on a plywood sheet with no or little hardware. Designing flat-pack furniture is not a new invention – the technique was popularised (if not perfected) by IKEA several decades ago. Considering the only novelty is adapting the designs to existing digital fabrication methods, the OpenDesk project has made considerable progress in a relatively short time: the website lists more than 30 designs by a dozen designers and hundreds of makers, and has witnessed thousands of downloads. Unlike WikiHouse, which is a foundation, OpenDesk is a company that maintains the platform, provides royalties to designers and generates profit through commissioning clients. The platform also features a “Design Studio” – an online catalogue that gives the user the opportunity to suggest and rate flat pack furniture designs that they would like to see added to the collection, as well as a Workshop to submit and showcase built examples of OpenDesk designs.[2] These additional features of the platform replace such traditional market research methods as focus groups and satisfaction surveys. A simple submission form on the website collects suggestions: “I wish OpenDesk would [let me do something I can’t do]” (OD, Wish). Neither an absolute consumerist wish list, nor a complete self-reliant DIY attitude, OpenDesk seeks to appeal to everyone else in-between. A common misunderstanding is that Open Making is essentially “DIY v2.0” – home improvement with a superfluous high-tech edge. However, Open Making is not meant to preach absolute self-reliance or a return to traditional craftsmanship. Instead, it proposes a “new deal” between designers, makers and users, bypassing the existing market structures and generating new forms of social relations. Open Making may attract several subjectivities. A designer looking for global recognition and distribution without having to go after mass-market consumerism can choose “their own licence terms and retain all the rights to their work” (OD, Designer). A maker that seeks to generate a new source of income can produce “well-mastered designs for local customers” (OD, Maker). For a potential IKEA customer that prefers a local, fair-priced and personalised alternative (or any consumer who would like to have “designer furniture”) but that cannot afford it, OpenDesk can fulfil such needs and desires. Put together, they claim to be “building the world’s most equitable & distributed supply chain” (OD, Designer).

This radical inclusivity and extreme accessibility demands an appropriate method for the testing of these claims so as to gain a more nuanced understanding. Beyond the study of discourse and visual representations, and the analysis of blueprints and artefacts, it is also possible to engage with the production of the object itself. If Open Making results in a multiplicity of non-industrial, non-market based unique objects with common characteristics, then there is no single supply chain or predominant consumer profile to analyse. Instead, understanding the unmediated subjective experience of the production process can reveal aspects that the mediation of words and images cannot. In this way, the prefigurative possibilities of the project can be grounded in hard facts and current challenges, rather than remaining at the level of theoretical speculation of its future potentials. By building the objects myself, I intend to reveal and explore the social relations that are invisible in the final product. While not a complete practice-based or action research methodology, this self-reflexive exploration can therefore help to bring into focus the subjective processes that shape (and are shaped back by) the technologies employed in the making. Trained as a designer, but a complete beginner as a digital manufacturer, the multiple subjectivities I inhabit will help me engage critically with the project and interrogate the principles of Open Making first hand. First, as a designer, I will study the readily available blueprints and modify and adapt them to my personal use. Once the designs are ready, I will then assume the role of the maker and fabricate the objects with a CNC miller. At the end of the production process, I will finally become the user of the objects, without being a consumer in the market sense. More than a consumer object, an office desk and a chair constitute the minimum physical infrastructure for intellectual labour in which I engage as a researcher. Hence, by producing OpenDesk furniture for my own use, I become a case study for the self-production of the means of production. Following the Marxian dialectic, not only will I be producing an object for myself, but my own subjective relation to the object will also be produced in that process.

[1] CNC, standing for “computer numerical control”, is the general term used for digital manufacturing machines featuring the automated control of tools.

[2] Newer versions of the website after 2016 no longer feature the Design Studio, but provide more information for designers and makers to get started with Open Making.

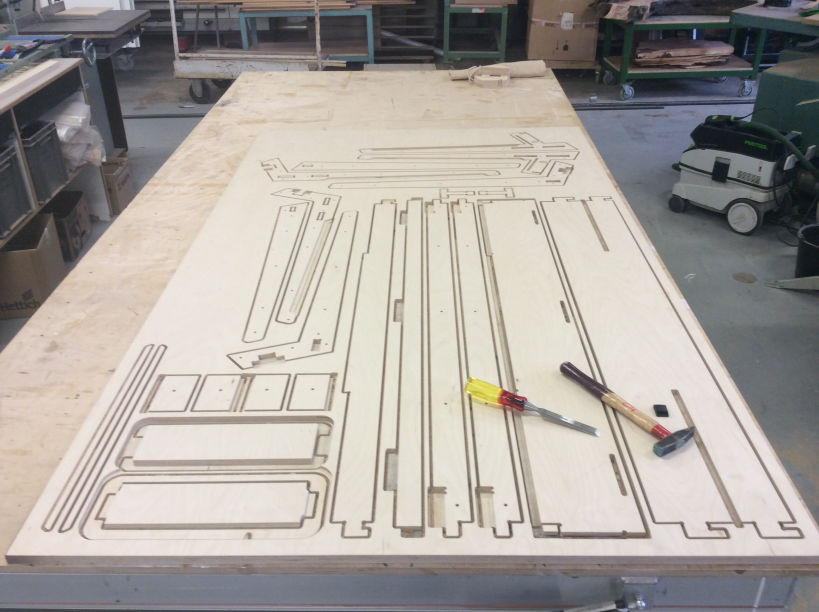

The journey to make one’s own OpenDesk starts without an IKEA catalogue or trips to the “big blue box” outlets. Not unlike any other e-commerce experience, the online catalogue is the starting point for the choice of furniture. The website features beautifully photographed workshops in Mexico, Brazil and England, capturing makers operating CNC millers, sanding, gluing or finishing furniture pieces, illustrating the fair, wholesome conditions in which OpenDesk products are claimed to be made. Examples of the various mgels made of birch plywood are presented in airy, contextless photography (with some models also viewable in augmented reality) are presented next to descriptions filled with superlatives. Within the range, two models stand out for personal use. The Layout Table by Josh Worley comes with a single customisable drawer and a reversible tabletop, designed for creative work; while the Studio Desk by Joni Steiner is more appropriate as a computer workstation, featuring a cable tray and a customisable access cover. Both products appear then as designed both by and for the designers themselves. In a sense, as creative and knowledge workers, they become their own target audience. Next to the desks, two chairs are also worthy of mention: the Kerf Chair by Boris Goldberg is striking with its bent surface and use of colours, while the Roxanne Chair by Pierrick Faure seems to be the simplest model with the most efficient use of materials. For the purpose of this study, I have chosen the Studio Desk v1.1.3 together with Roxanne Chair v2.0, which are cut out of two sheets of standard 18 mm thick 2440x1220mm plywood. [fig. 11] By downloading the cutting files, I was granted a Creative Commons BY-NC license, which allows me to share and modify the designs as long as I provide accurate credit, and produce for non-commercial uses. This is the crucial moment, being without market mediation, marking the beginning of the free circulation of design blueprints, thus enabling further non-commercial instances along the production process.

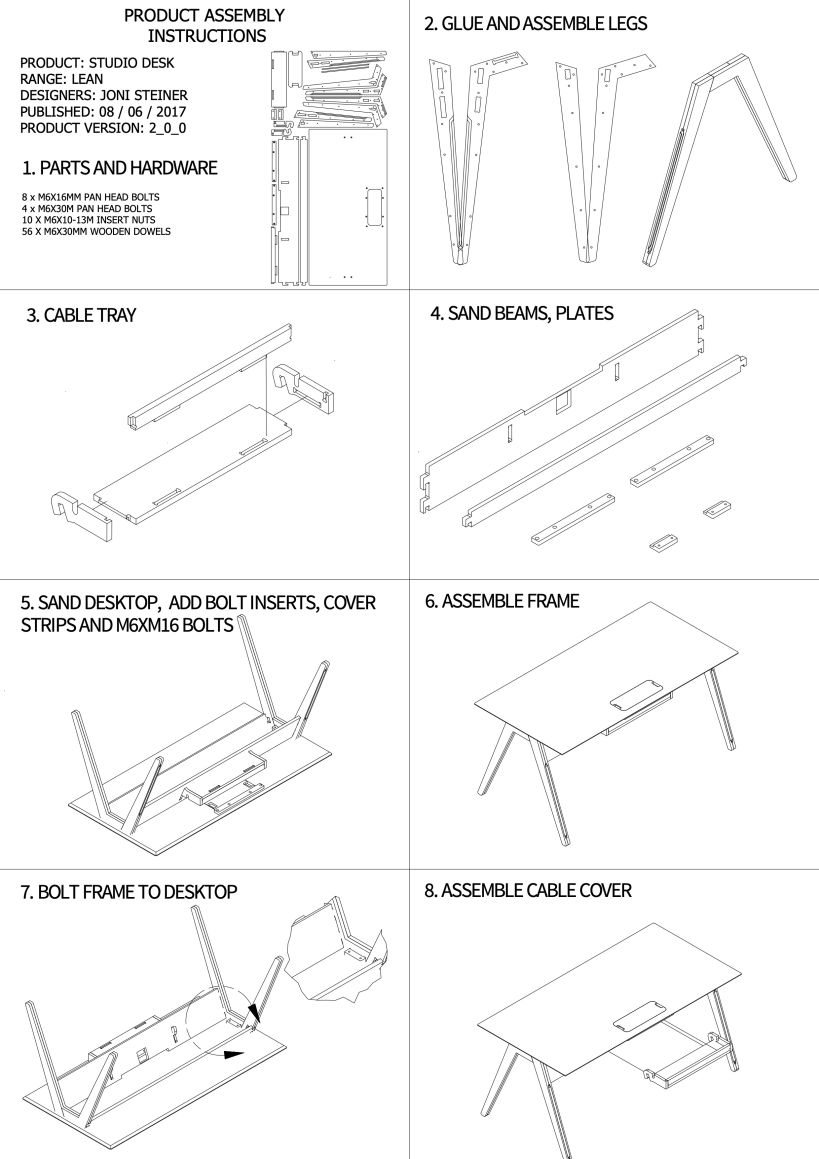

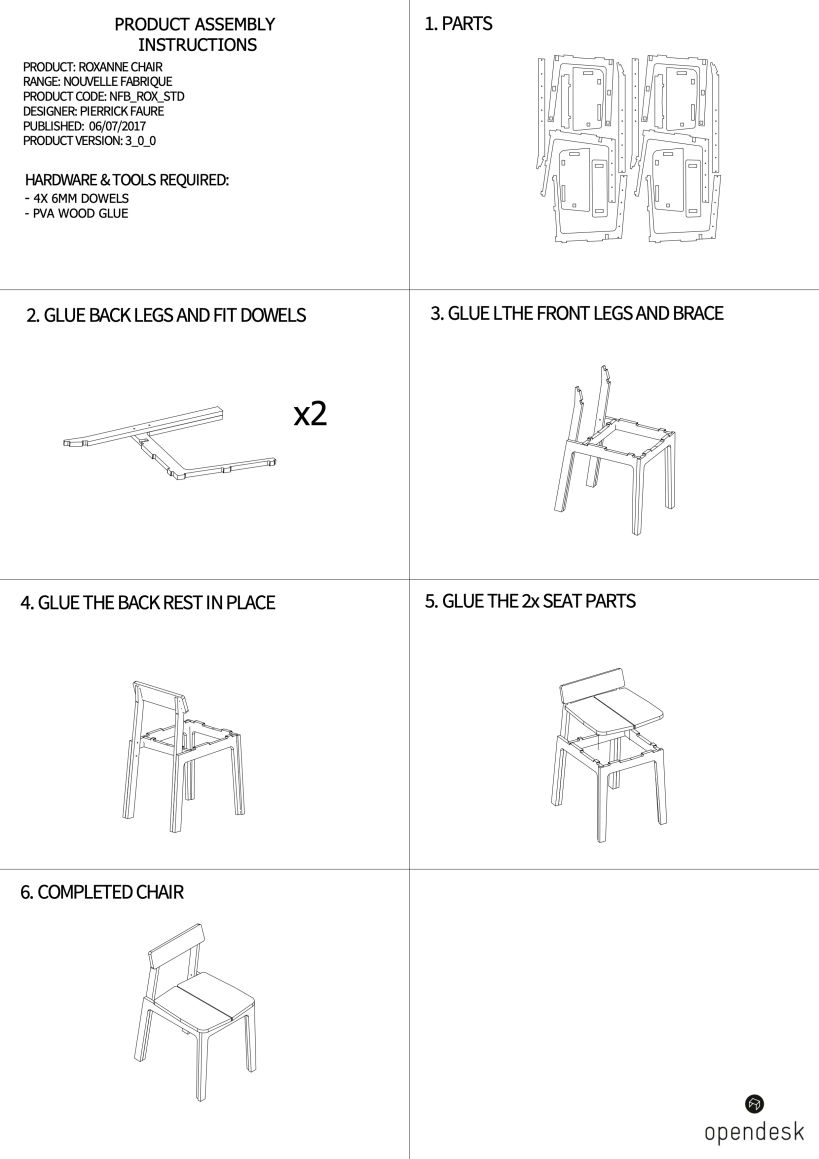

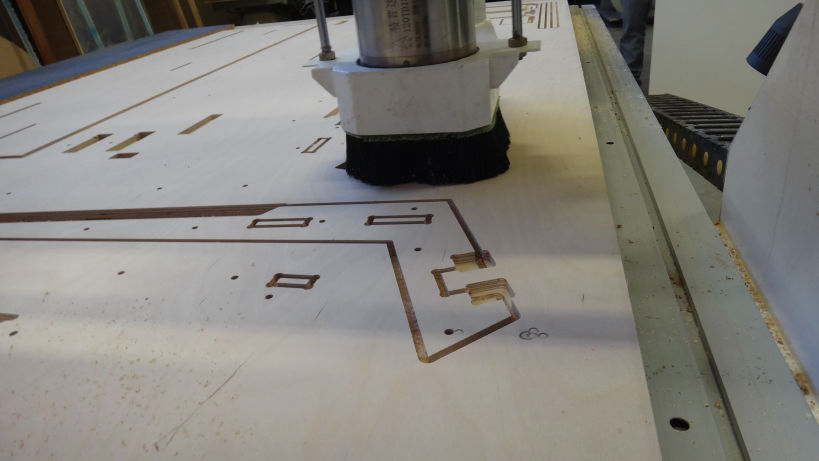

Since orderly, informative and well-presented documentation is essential for the reproduction of an open blueprint, all of the knowledge made available for potential makers warrants particular attention. The blueprint itself comes as a DXF file (universal format for computer-aided design models) containing the drawings [fig. 12]. In the course of the project, I identified several errors in these files,[1] and so a detailed study of the blueprints, which are shared “as is”, is very important, since the responsibility for any errors resides entirely with the maker, as expressed explicitly in the terms and conditions, with no guarantees provided by OpenDesk. There are also some generic fabrication guidelines explaining the basics of CNC machines, but since the software may vary from one machine to another, it is impossible to cover every eventuality. Once the pieces are cut, however, the rest is supposedly straightforward [2]: a typical guide in axonometric projection presents step-by-step assembly instructions for the desk, including the required tools (such as a mallet, glue and sandpaper) and explanations of various types of fit and finishing [fig. 13]. The website also features an extensive FAQ for designers and makers, which covers most of the specifications for the entire process. While the documentation may appear exhaustive and perhaps even intimidating for a beginner, it remains incomplete, as some crucial information is nowhere to be found. For instance, there is no indication of the weight of the final object, no transparently listed cost sheets, and no approximate cutting or finishing time, which are perhaps the essential pieces of information for a professional. In other words, there is no way to “preview” the entire process without a prototype – in short, part of the knowledge is only attainable by experiment.

Before initiating this experiment, I devised an exceptionally convenient scenario. I would borrow a shared cargo bike to pick up the sustainable Baltic birch plywood sheets from the nearest lumber store and take it to the neighbouring maker-space, both situated less than a kilometre away from my home. The local shared machine shop offers, among other digital manufacturing tools, a self-assembled CNC miller. This would have been an ideal prefigurative practice, demonstrating a production process almost entirely disentangled from global markets and industrial infrastructure (with the exception of the engineered wood), although it soon became apparent that this was an overly optimistic expectation. First, since the lumber store was out of stock of the desired material, I ended up visiting three more stores to compare their prices—acting according to the rational market behaviour of a self-interested individual. Between the cheap but uncertified and high quality but expensive options, I chose a middle-range, FSC-certified plywood, which had to be picked up by a van. Another challenge was arranging a place to cut the plywood, since the maker-space nearby lacked the staff to supervise the CNC miller for an entire day; with only a few volunteers who did not yet know how to operate the self-built machine. In the end, a private workshop in Krommenie (25 km north of Amsterdam), shared by six craftspeople, generously offered to facilitate the process. I may have been particularly lucky to find this opportunity to use the machine for free, as it could have cost more than €40 per hour. Maartje, the furniture maker who taught me how to operate the machine, explained that the CNC miller was acquired mainly to obtain curved shapes for their high-end, unique furniture pieces, and said that this would be the first time it was to be used for a low-cost, open design project. It was mutually beneficial to find a common ground of experimentation and learning falling between my technological fascination and her aesthetic interests.

Over two workdays, under the curious gaze of Maartje’s colleagues, we operated the machine to cut the two plywood sheets. [fig. 14] Having studied the files in depth and being very much at ease with computers, I quickly grasped the intricacies of the process. First, the pockets at multiple depths, then the cut-outs, while being careful about whether to cut inside or outside the lines. There are many more parameters that need attention, such as the choice of cutting bits, speed of rotation, number of passes, the inclusion of tabs. In other words, the blueprints do not come “ready to print”, as one needs to understand how and where each piece fits, to determine the right face then to cut them. While a less customisable, simplified version of the cutting files suited to quick and standardised production by non-professionals would conceivably be possible, the threshold is currently set to require the knowledge and experience of makers, which is more likely to deliver higher quality results. Simply put, it is similar to the perceived differences between the Linux and Mac operating systems. For some, the full freedom to modify every parameter is considered “more democratic”, even though increased complexity ends up excluding most people. Conversely, for others, simplified processes are more accessible for the masses, even though they limit opportunities to hack and master the process — a conundrum requiring strategic choices or balancing acts with possibly more than one solution.

Coincidentally, an hour after having starting to cut the first sheet, OpenDesk’s production manager sent me a slightly revised version (v1.1.5) of the desk. For a moment, I felt the same regret experienced when one’s latest technological gadget gets supplanted by a newer model, rendering the old one less desirable. In the commodity-machine, this planned obsolescence is a driver of consumption and growth, but in this case, changes are predominantly introduced to improve the manufacturing process rather than the final product, and so my desk, based on that earlier blueprint, remains essentially the same as the new version. Based on the feedback by makers and users, the blueprints for both the desk and the chair have been updated over time (to v2.4.0 and v3.0.0 respectively), with the new versions offering increased material efficiency, a simplified assembly process or minor stylistic changes. In November 2017, a comprehensive “Tailoring” service was introduced for more than a dozen products. Using parametric models, it became possible to generate custom-sized blueprints to suit the exact length and width specified by the end-user, with some workstations shapeshifting between single-person to four-person dimensions, or meeting tables that accommodate from 8 to 14 people. Instead of standardised, one-size-fits-all designs for mass production, on-demand production makes both the blueprint and the artefact adaptive, resulting in an almost infinite number of variations to the original design. This testifies to OpenDesk’s approach to blueprints as software; even though artefacts get frozen in time, the blueprint lives on.

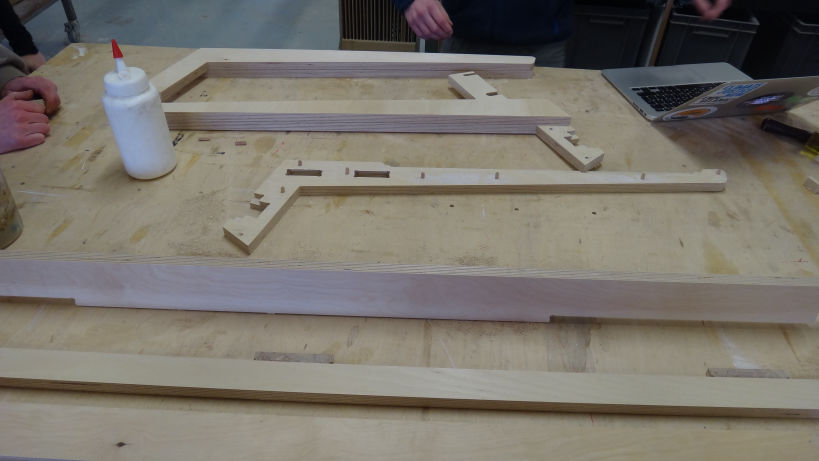

Just as the blueprints do not come “ready to print”, the cut components are not exactly “plug and play” either. Similar to a stack of printed paper that requires handcraft to be bound into a book, transforming the raw puzzle pieces into a smoothly finished piece of furniture is still the most labour intensive stage of production. The multiple sandings, oiling and assembly took no less than three additional workdays. These were undoubtedly not hyper-efficient, productivist working hours, but more akin to the slow-paced, gratifying time spent by a craft hobbyist. Eliminating stocks and producing on-demand, the time necessary to obtain a finished product is certainly longer than the streamlined assembly line to the big-box retail experience, which explains the high costs associated with commercial production. While I did not take the commercial route, my experience was similarly unlike to DIY – I did not design the furniture myself, nor did I cut the wood by hand or assemble it alone. Thanks to the commoning of blueprints and machines, my role was one of maker, with a quite distinct set of responsibilities and sense of pride than a designer or a carpenter. Knowing that I used a blueprint created by a designer that worked on it far more than I could do by myself; knowing that I operated a machine infinitely more precise than my hands could ever be; and knowing that it is the product of a voluntary effort by many, the values that were at the forefront were cooperation rather than competition, sharing rather than selling, and joy rather than profit. Far away from the commodified satisfaction of a consumer feeling rewarded by the shopping experience, having witnessed the entire process, having known the wood in its raw form and the blueprint on the screen, I can take non-alienated, non-commodified pride in self-production. The resulting furniture is neither an artisanal object nor an industrial product, being of higher quality than that produced for the mass market, but more affordable than artisanal woodworking. It is yet to be seen how such furniture ages, but it is certainly not of the disposable kind.

[1] The test cutting sheet was not functional, and a pocket to be cut on the reverse face of the tabletop was on the front face instead. These issues have been solved on later versions of the files.

[2] The assembly guide for the chair was not available at the time of production, but it was relatively easy to put the 10 pieces together.

Whether its democratisation of design, its populist market expansion or its production of commons, the claims and intentions of Open Making are worthy of in-depth study to interrogate their accuracy and the extent to which they make a strong and effective move to unsustain the commodity-machine. After having presented the vision of Open Making and experienced the production of OpenDesk furniture, it is now possible to interrogate how close the claims come to reality. The economic performance of the project is the first aspect to assess, since the comparison of its commercial and non-commercial options as well as the market competition, as exemplified by IKEA, can provide the basis for further speculation on its impacts. Unlike a commercial product that benefits from countless Amazon customer reviews, I had almost nothing to consult to decide whether it would be a sound investment of my time and money. An opinion piece published in Dezeen magazine provided an unambiguous warning of how costly the operation would be: according to the author, the simplest children’s stool (OpenDesk’s Edie Stool) – stated to be a rather low-quality product – had cost £170 (McGuirk).[1] Undeterred by the estimated price indication of €500 (excluding VAT) for the Studio Desk, I requested quotes from local makers via the OpenDesk website before starting my own production, but received only one response from a workshop in the industrial harbour of Rotterdam matching the estimation, and with more than 20% added for platform fees and honorarium for the designers. It would be safe to state that the commercial production of OpenDesk furniture is far from competitive, let alone affordable. Rather than intimidating potential makers and redirecting them to mass-produced options, this limitation may be a blessing if it encourages consumers to opt for self-production methods.

At the end of the process, the commercial price tag can be compared with the actual costs I incurred in my non-commercial production. The moment of purchase of two plywood sheets in exchange of €150 marked the essential market-mediated instance of the production.[2] The acquisition of raw materials constitutes the current limit to non-market relations – a seemingly inevitable stage of monetary exchange that will remain as long as the highly automated wood processing remains a commercial operation. This exchange, however, takes place in the first stage of the production process rather than with the consumption of the finished product. Shortening the commodified value chain and expanding non-commodified relations, the value added in the later non-commercial stages does not translate to higher prices. In other words, putting a value to the labour time and strictly considering the material costs, the cost of self-production is a fraction of the value-added market price—even less than the 20% mark-up for the designers in the commercial method. Self-production is also surprisingly inexpensive when compared to the predominant mass-produced alternatives, and there are no equivalent products at IKEA obtainable for a similar price. Labour is without doubt the main factor in production and leading source of value, and is the most critical piece of the process to be disentangled from the commodity-machine. For the current project, I utilized my own, free and autonomous production rather than employing anonymous, alienated and low-paid wage labour. I was thus able to benefit from the social relations of commoning – I downloaded the open blueprints, I was given access to an idle CNC machine, and a carpenter friend dedicated his time and labour. None of this is accounted for in monetary terms, although there is an indisputable creation of value, as encapsulated by the furniture itself. In his opinion piece, McGuirk dismisses the social value of Open Making, arguing that “there’s nothing particularly ‘social’ about watching a machine drill through plywood to some algorithmic configuration”. This misses the point by searching for socialisation in the machinery, while it is precisely during the rest of the process that social relations are meant to occur. In my case, it was fortuitous and ephemeral social relations that enabled this value creation, whereas for McGuirk’s children stool, these options must have been unsolicited or absent. The generalisation of such practices requires socialised institutions to provide a viable alternative to commodified relations.

Such logistical, financial and social factors serve to highlight the limitations of relying on the power of blueprints alone. However ingenious a design may be, its blueprints may not sufficiently communicate everything about the project from start to finish. While design blueprints can easily be shared, the rest of a project often remains opaque, since many factors are determined locally and cannot be easily generalised. Every replication potentially provides additional insights into making, and yet the knowledge produced by end-makers will remain isolated unless they are encouraged to document and share their findings. The more a design project is encapsulated in a blueprint, or alternatively, the more complete a blueprint becomes (making the entire project predictable), the more likely it will be adopted, circulated and reproduced, and hence the more successful that project becomes in terms of Open Making. In other words, if a project contains no blind spots in publicly available information, then it is more likely to achieve widespread circulation. My personal experience with the OpenDesk project may not amount to much in terms of extrapolating its conclusions to speculative heights, but it nonetheless marks a modest starting point for questioning its economic disruption potentialities. In a video interview featured in the Guardian with the bold title “A revolution in furniture design”, Nick Ierodiaconou, co-founder of OpenDesk, is asked the provocative question: “Is this an anarchist furniture movement trying to topple the centralised industry?” The designer responds cautiously, claiming that it “doesn’t necessarily need to subvert the existing market (…) the extent in which that will compete or not remains to be seen” (Wainwright). Elsewhere, OpenDesk’s goal to reach the mainstream is perhaps best expressed as “[doing to] IKEA what Airbnb is doing to the hotel industry” (Hickey) —unlocking previously untapped distributed potential without massive investments in industrial infrastructure. Indeed, the idle capacity of the CNC-machine in the workshop where I cut my plywood sheet could be repurposed for the manufacture of more affordable furniture than their high-end products. Yet this comparison still obfuscates the crucial differences between Airbnb’s rent-extractivist business model and OpenDesk’s non-commercial Open Making, which allows and encourages non-market possibilities. In some sense, OpenDesk offers from one platform the non-commercial Couchsurfing-model alongside the commercial Airbnb-model. Asking whether OpenDesk is as disruptive as Airbnb (in both its positive and negative implications) may be misleading, in that disruption through direct competition ends up producing interchangeable commercial enterprises. It may instead be more relevant to see it as a form of détournement, subverting the platform economy to unleash its commoning potentials. In the case of OpenDesk, some physical and social infrastructure is needed, alongside the digital platform, for its widespread adoption. Maker-spaces offering CNC-machines to public service akin to libraries, and basic universal income schemes liberating labour time would have such effects. In other words, while OpenDesk alone does not constitute a viable alternative all by itself, its combination with other postcapitalist measures could bring it to the same level of convenience and accessibility as libraries and photocopiers.

A welcome statement introduces the assembly guide: “The product you have in your hands is the result of a new model sitting at the union of the internet, new advancements in digital technologies, and age-old making techniques. We call this Open Making” (OD, Assembly 3). The first time I read these lines, I had no product in my hands, but only a PDF document on my screen. Why would an assembly guide downloaded together with the blueprints, manifestly before the production of the physical object, make such a factual distortion? Perhaps this amounts to the last vestiges of the typical copywriting devices of marketing. After all, no advertising or packaging precedes the experience of a non-commercial product; and there is no interface other than the assembly instructions to communicate as close as possible the final object. This struck me as a challenge to introduce a textual element to my production. As a modest creative intervention, I decided to engrave the two epigraphs of this thesis on the back support of the chairs [fig. 15]: “[We live in] a civilisation in which we produce nothing of what we consume and consume nothing of what we produce” and “Apocalypse is always easier to imagine than the strange and circuitous routes to what actually comes next.” With the former quote by André Gorz, the chair itself becomes evidence to the possibility of surpassing such a civilisation, introducing, however small, an instance of reunited production and consumption. The second quote, by Rebecca Solnit, suggests that even though the crisis of the commodity-machine may appear to be inescapable, viable alternatives may be disguised as pieces of a plywood chair, waiting to be assembled. Together, these quotes testify to the intertwined prefigurative and speculative dimensions of postcapitalist design.

The most remarkable statements from OpenDesk surfaced one year after my adventures in self-production, when the company professed their principles and values in a Charter.[3] Alongside such expressions as “positive change”, “people and planet” and “consciousness and inclusivity” (which are rather commonplace in the literary genre of corporate responsibility), a few others stand out. For instance, “to generate value for our community, rather than replacing jobs through robotic automation” and “replacing ‘Business as Usual’ with ‘Business as Mutual’” strike as novel commitments that are in line with postcapitalist intentions. More notably, there is an entire section dedicated to their learnings in experimentation with open blueprints:

These principles cover much more ground than a Creative Commons licence. It would appear that relaxing intellectual property regimes and preaching about the commoning aspect of open blueprints is nowhere near enough to sustain a practice with coherent values – openness must be a much more generalised attitude that transcends the modalities of circulation for open blueprints. It requires foundational engagements that affect every aspect of their enterprise, being at odds with competitive and exploitative markets. In other words, more than the mere knowledge of how to produce an artefact, it is the blueprint of the entire business model around the product that is meant to be open-sourced. In the next section, I explore the multiple meanings of openness and study OpenDesk’s sister project WikiHouse, which presents more elaborate institutional arrangements to engage in long-term endeavours.

[1] In reality, the author misrepresents the costs, producing only a single stool from an entire plywood sheet. When produced in a batch of eight, the OpenDesk website estimates €54 per stool.

[2] While the workshop with the CNC machine was offered to me for free, I nonetheless donated €50 to cover some of the expenses, including electricity, milling bit, sandpaper, glue and linseed oil.

[3] Ironically enough, the Charter itself is not publicly published on their website, but accessible only through a special section dedicated to on-board partnering designers, makers and employees.

Having explored the technical, economic and social advantages of the digital reproduction and dissemination of design blueprints, I can now turn my attention to the concept of openness and the current debates and practices surrounding its multiple meanings. Are the freely available and accessible blueprints easy to understand? What institutions are supporting the development and dissemination of the project? How do open blueprints achieve circulation without a market? The politics, claims and characteristics of WikiHouse will be subjected to an in-depth study to conceptualise openness beyond commoning blueprints. As the project will demonstrate, openness comes in degrees, with either more or fewer parts of the process being demystified. I evaluate the successes and limitations of WikiHouse and conclude that openness requires custodian institutions if it is to be sustainable.

Created with Mobirise - More