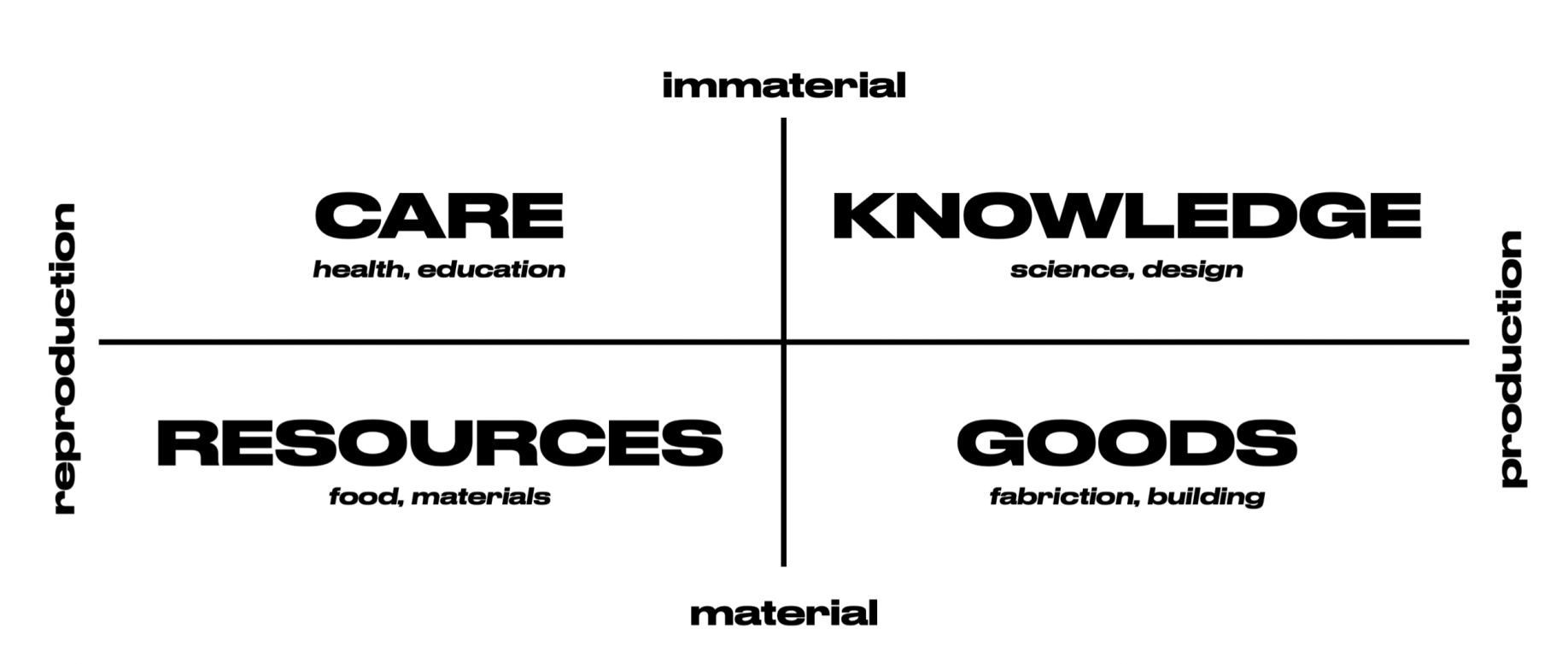

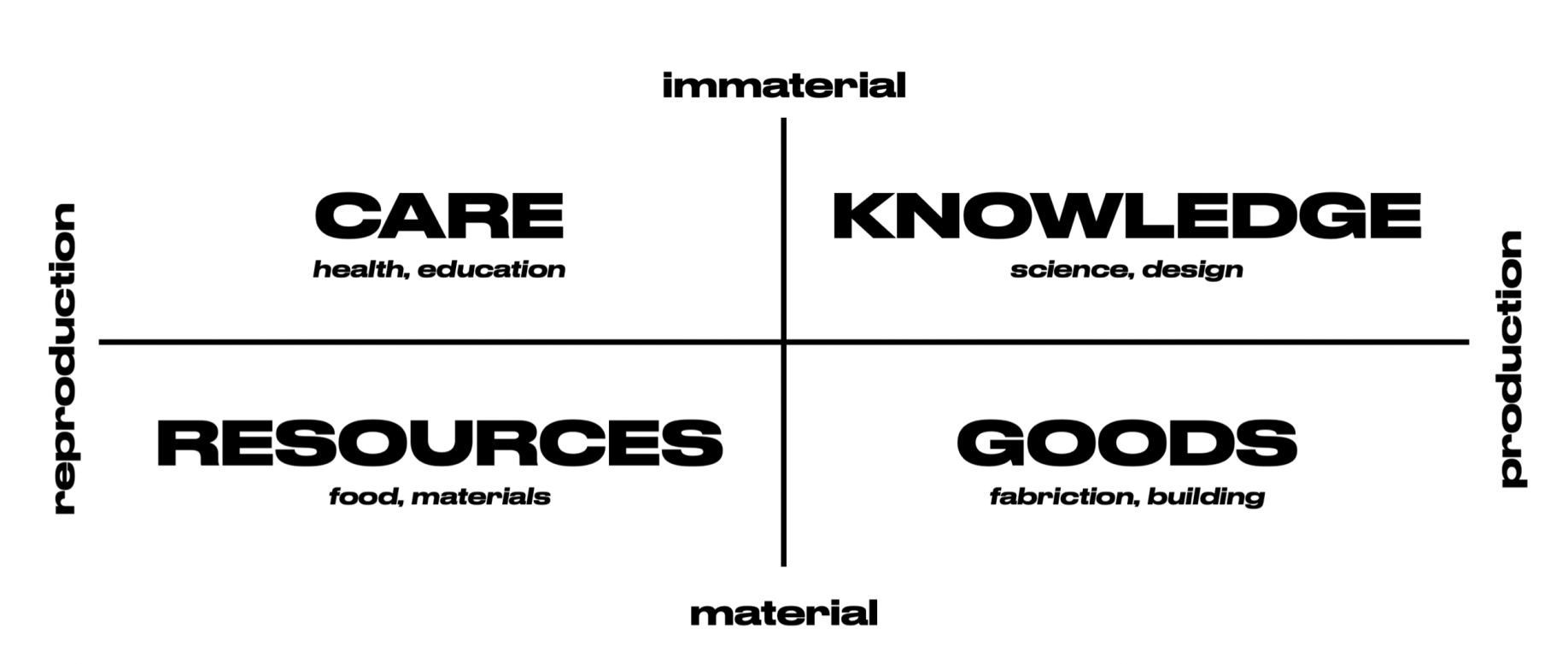

Table 3. Commoning in four quadrants [2]

Postcapitalism comes with a rich prehistory of desires, experiments and struggles that are all but impossible to do justice to within the scope of this thesis. I will nonetheless try to establish some continuities and to clarify some new characteristics that are relevant to the political economy of design. The initial literal meaning of postcapitalism related to its conceptualisation as a temporality – what happens after, or beyond, capitalism. Lacking the ability to predict the future, we must rely on our mental faculty to imagine a future without capitalism. This is certainly not a new interrogation, as many non-capitalist utopias have been envisioned since the dawn of the industrial age. However, the term “postcapitalism” is rarely employed in early studies of political discourse or social sciences. Socialism and communism were the original names given to non-capitalist futures, which describe coherent, positive narratives about how social and economic relations are (meant to be) organised, how value is produced or, simply, how lives are lived in the absence of capitalism. These terms do not prescribe the immediate aftermath of the grand revolutionary finale nor exactly the process of getting there, but describe something occurring much later, once the transition to a new state of affairs is complete. Until the 1960s, the predominant belief was that the end of capitalism would be arrived at by means of a full-blown revolution stemming from a social uprising. With the growing disillusionment in the Leninist road to communism and the subsequent collapse of really-existing-socialism, these approaches have increasingly been dismissed as unrealistic, if not downright delusional. The disappearance of the alternative from the world map has paved the way to “capitalist realism” (Fisher), notably with Francis Fukuyama to (prematurely) declare the “end of history”, after which capitalism was supposed to extend into eternity. As revolutionary politics were on the retreat, the risk of a nuclear catastrophe emerged in parallel; and hope was eclipsed by fear as the agency of radical change shifted progressively from mass movements to out of control complex systems. In his epoch-defining musings about the end of the world being easier to imagine than the end of capitalism, Fredric Jameson remarked “perhaps that is due to some weakness in our imaginations” (Seeds xii). The collective desire to conceive a better outcome appears to have been supplanted by the fixation of the collective psyche on an imminent global breakdown, whether it was to be capitalism causing an ecological meltdown, or the ecological meltdown causing the end of capitalism. Given this, is it even reasonable to speculate on postcapitalism?

If anything, the end of really-existing-socialism should teach us that even too-big-to-fail constructs can dissolve unexpectedly, and there is no reason to believe that capitalism should be exempt from such a fate. It is reasonable to expect that the end of capitalism will sooner or later follow the end of socialism – after all, History appears to continue, if not towards progress, at least towards entropy. If capitalism is an organism with a finite lifecycle (Mason), a linear periodisation could be proposed as follows: pre-, early-, late- and post-capitalist eras. At the same time, it should not be assumed from the unexpected and rapid dissolution of the (heavily centralised and hierarchical) Soviet system that the only imaginable ending for capitalism is an abrupt one. While the 2008 market crash could not immediately shake off the hegemony of capitalism, it undoubtedly triggered a widespread recognition of its finitude, as well as the legitimacy and urgency of imagining alternatives. Accordingly, recent debates following the financial crisis are less interested in long-term utopian visions and more concerned with the near-future radical transformation of capitalism. The distinctive feature of the term postcapitalism is then its resistance to the temptation of conceiving the end as a complete abolition of the current status quo – whether via an instant overthrow or a sudden collapse. There are other, far subtler and deeper ways to conceptualise an ending, in that transitions from one period to another are not clear-cut moments in history, but rather periods of incremental change, where marginal, parasitic practices expand and eventually become dominant. Capitalism itself did not become hegemonic overnight, but was rather a result of a centuries-long disintegration of the feudal model, and its concurrent and seemingly haphazard substitution by a combination of emerging political ideals, technical breakthroughs and social formations. If the transition to capitalism was gradual, so could be the transition to postcapitalism – or rather, postcapitalism would be the name of the period of transition into something yet to be named.

Admittedly, the term shares the unfortunate ambiguity of the concepts “post-industrial”, “post-colonial” and “post-modern” – none of which resulted in the actual end of industrialism, colonialism or modernity as such. In the same way, postcapitalism risks conveying a false sense of “moving beyond” capitalism, without really implying its disappearance. Perhaps a more realistic (and deliberately reformist) goal could be formulated as the immediate replacement of neoliberalism, without challenging the entirety of capitalism. The case for a gradual transition can also be justified by the level of complexity of capitalist globalisation, which would require an equally multifaceted, distributed and cumulative replacement. Among others, Srnicek and Williams champion this approach. While their 2015 book “Inventing the Future” is unambiguously subtitled “Postcapitalism”, they admit that some of their proposals “will not break us out of capitalism, but they do promise to break us out of neoliberalism, and to establish a new equilibrium of political, economic and social forces” (chap.6). If postcapitalism is meant to follow the current late-capitalist neoliberal era, a relevant objection would be that such gradualism qualifies as post-neoliberalism. Similar to historical social-democratic reformism, this would temporarily resolve the contradictions and introduce a qualitatively different form of capitalism. Then why insist on a term that promises more than it can deliver? As will be argued below, there are strong reasons to believe that the unique historical conjuncture of the early twenty-first century justifies more than ever the conceiving of the end of capitalism. The premise of reformed capitalism would only hold if its contradictions were strictly internal (extreme concentrations of wealth, inability to invest idle capital, sluggish economic growth, etc.), although it is in fact on a collision course with (or has already broken through) multiple external, ecological limits.

However imperfect and temporary it may be, a “reality check” informed by climate science can help contextualise the current stakes and the road ahead. As probabilistic scenarios indicate, to have more than a 50% chance of avoiding an irreversible and abrupt climate meltdown, curbing the greenhouse effect requires multiple swift measures running in parallel, such as reversing deforestation and reconfiguring agricultural systems. However, the determining factor remains curbing the carbon emissions of fossil fuel-based energy systems. This entails halting their exponential growth rate with a momentary peak or a brief plateau, followed by a period of rapid decline at a rate at which emissions are halved every decade until complete decarbonisation is achieved by the mid-century (Anderson and Bows 30). Given that such a steep curve of radical reductions would be immensely disruptive for every industrial system that relies on fossil fuels (agriculture, construction, heating, transportation, to name just a few), reversing the trajectory of carbon emissions entails a far more fundamental redirection than a switch in energy supply from fossil to renewables, or from neoliberalism to green capitalism. The “health” of a capitalist economy is indexed to the growth of its GDP, and economic growth has depended consistently on fossil fuel-based energy since the dawn of the industrial revolution (Malm). There is no empirical historical evidence, nor any rational basis to suggestions that economic growth can be decoupled from its appetite for energy, especially considering renewables cannot substitute the intensity of fossil fuels, and are themselves dependent on finite resources. In fact, scholars from diverse disciplines agree on the premise of degrowth, being the impossibility of infinite economic growth on a finite planet (Heinberg; Jackson; Kovel; Magdoff & Foster; Frankel), and that radical reductions (in the order of 10% annually) remain incompatible with a growing economy. In short, peak-carbon and peak-growth are linked inseparably to one another, although they may not occur at the same time.

Of course, the end of capitalism can be either “by design or by disaster”, and the alternative to radical reduction scenarios remains the exhaustion of the carbon budget in as little as one decade, with worldwide catastrophic impacts by the middle of the century. It is highly unlikely that it will be possible to sustain an integrated and growing global economy in the presence of extreme weather patterns, unreliable food supply, mass migratory flows, increased conflict zones, unsustainable nation-states and other consequences. While undesirable, a chaotic disintegration of globalisation would still be a radical rupture from the overall path of the recent centuries, and the beginning of a long-term tendency that is ultimately incompatible with the very foundations and aspirations of capitalist economies. Considering the intertwined history of fossil fuels and capitalist economies, Imre Szeman proposes “to think about the history of capital not exclusively in geopolitical terms, but in terms of the forms of energy available to it at any given historical moment” (806). Following this insight, and given the correlation between the volume of carbon flows and the intensity of capitalist relations, the question is then no longer whether carbon emissions will ever peak, but rather how soon they will be made to peak, and whether the decline can be managed without collapse. Whatever the outcome, the climate-carbon-capital nexus allows us to conceptualise our current conjuncture as Peak Capitalism.

A peak is not an endpoint; and it is neither a sheer cliff nor the bottom of a pit. Unlike a revolution or a collapse, a peak is a virtually unnoticeable shift that can almost go unnoticed, only to be confirmed retrospectively. Yet that little shift changes everything, because the previously established rules, habits and assumptions no longer hold, and what was once impossible becomes inevitable. The same grim ecological outlook that weakens the imagination paradoxically provides an alternative attitude towards the timeline of the transition. Just as ecological collapse is not a single apocalyptic moment but a continuum towards multiple tipping-points of no return, responses to it are bound to multiple hard deadlines. The urgency in mitigating climate meltdown means working against time, without waiting for the revolution nor the collapse: a revolution can be postponed indefinitely into the future, just as reformism does not come with a “countdown” after which no half-measures would be available. Instead, peaking combines the pragmatic gradualism of the transition with the concrete necessity of swift action. This cannot be indefinitely postponable, since it comes with a rather narrow time frame that has far-lasting consequences for the centuries to come. This duality echoes the intertwined nature of resistance and its alternatives – the hard deadline requires concerted effort to politically enforce the peak, while the continuous weakening of capitalist relations will depend on the availability of alternatives. In this sense, postcapitalism, as suggested here, is not a simplistic assumption of an inevitable historical outcome, nor is it an option that is indefinitely available, being rather an acknowledgment of the urgent necessity to seize a one-off opportunity. Simply put, the temporality of postcapitalism implies an emergency pathway – missing this opportunity, the only remaining outcome will be the disintegration of the global civilisation alongside the mass extinction of other species.

Given the stark choice between the ungraspable consequences of a failing climate, versus the relatively modest tinkering with the (hu)man-made economic systems, it should be arguably easier to believe in the likelihood of the latter. What is implied here is the assumption (and hope) that it is possible to have intentionally and quantifiably “winding down” of capitalism without a cataclysmic crash. Having less-and-less-capitalism depends on desiring, then enacting and finally recognising the material confirmation of a quantitative peak in capitalism as the dawn of postcapitalism. Postcapitalism is then the extended, undefined period triggered by the peak, in which capitalist relations start to retreat, but do not disappear completely. While it is likely capitalist relations will linger throughout this century, what is uncertain is whether they will maintain their hegemonic – and ever-expanding – position. Even though the process may be “combined and uneven”, the overall global trajectory of piecemeal and ad-hoc steps would be only a quantitative regression of capitalist relations over time. It may not bring about a qualitatively distinctive kind of culture in the immediate, but without the wholesale supersession of capitalism by another coherent model, the vacuum is bound to be filled, if not by another totality, at least by an un-totalisable multiplicity – an imminent “new normal” with its own contradictions and dynamism. Being not exactly an apocalypse, nor a revolution, nor a complete overhaul of the economy in a distant utopian future, postcapitalism is the harbinger of a gradual decline of the economic order, to be progressively surpassed by other modes of production and socialisation. After providing a sense of the temporal conditions and possibilities of postcapitalism, I will explore in the following sections the processes that provide the means for its actualisation.

I have so far considered postcapitalism only as a temporality. While this has allowed me to conceptualise novel (geological, social and even eschatological) “grand narratives”, such speculations are equally remote to the present, and lack engagement with the world as it is. In this section, postcapitalism is defined from an entirely different angle. Instead of waiting for the End (of History, of capitalism or the world), the main focus here is the search for the Exit. Like when faced with an emergency, the absolute distance to the “outside” may be less important than the availability of safe passage – a successful Exit depends on the escape route taken by those actively looking for it. In other words, the pressing concern when “exiting” is not the final destination, but the direction to take in the immediate, as what is done in the present is not a fleeting moment, but rather loaded with long-term consequences.

While many authors could be considered a point of departure for this specific meaning of postcapitalism, one figure stands out as exemplifying the transition between the old and the new approaches. French thinker André Gorz is somewhat of an exception among the Marxists of his time due to his positions against wage labour, his endorsement of universal basic income, and perhaps most notably, his pioneering work on political ecology. In his later years, he developed an interest in cognitive labour and information technologies as additional factors that aggravate the contradictions of capitalism. The following passage from his final text, published posthumously in 2008, encapsulates, with a confident (if not prophetic) tone, his core argument on postcapitalism:

Here, Gorz begins by identifying capitalism as a set of economic, social and productive relations based on “commodities, wages and money” – in a rather conventional Marxist analysis. Note that Gorz does not question how capitalism can be defeated, dismantled or abolished; his interest lies rather in how it can be surpassed, implying substitution by something that performs better. He restates these desires by specifying that the Exit ought to be taken in a “civilised” manner – and this plain yet crucial precision echoes the options seen a century earlier between “transition to socialism or regression into barbarism”, as popularised by Rosa Luxemburg. Indeed, a disorderly and hasty Exit may trigger a stampede, resulting in tragedy rather than liberation. In some ways, “surpassing capitalism” and a “civilised exit” express the same desire to bring change through resolutely non-antagonistic, non-confrontational means. Gorz’s most remarkable insight comes at the end of the citation, where he lays out a condition to the success of postcapitalism: our understanding of the already-existing “trends and practices” determine our likelihood of the “civilised” outcome. If the future ways of living are already discernible in postcapitalist spaces and the practices embedded in the here-and-now, they would definitely be worthy of analytical interest – not only would they provide a glimpse of the possible, but would also pave the way to their realisation. As neither a class revolt nor an autonomist exodus, this self-realising logic is the defining characteristic of postcapitalism – a prefigurative emphasis on how social change is actualised.

To pre-figure means “to anticipate or enact some feature of an ‘alternative world’ in the present, as though it has already been achieved” (Yates 4). Rooted in early utopian socialist communities, as well as in the Paris Commune of 1871, prefigurative politics were eclipsed by the success of Leninist-style party organisation in the first half of the twentieth century, only to be rejuvenated by the feminist, ecologist and pacifist strands of the New Left in the 1960s. More recently, the Occupy and Indignados movements have also been characterised by a strong prefigurative practice (Maeckelbergh). The term “prefigurative politics” was originally coined in 1977 by Carl Boggs as “the embodiment, within the ongoing political practice of a movement, of those forms of social relations, decision-making, culture, and human experience that are the ultimate goal” (99-100). While the term is often applied narrowly to practices complementing adversarial protest and direct action movements, it is possible to broaden its frame to include any cultural practice that valorises the means over the ends. Postcapitalist practices are not prefigurative only in the sense that they embody the present behaviours, techniques and values that belong to an intended future, in that, as Yates notes, building such alternatives “should only be seen as prefiguration (and can only be distinguished from subcultural or counter-cultural activity) when combined and balanced with processes of consolidation and diffusion” (18). Put differently, prefiguration is not necessarily about absolute purity and consistency with one’s values, but about one’s willingness to reinforce and spread its values further.

While the temporal/speculative approach to postcapitalism does not distinguish between its geographical discontinuities, spatial/prefigurative practices in the present are characterised by their confinement in particular locations, and in their contours defined by the spaces of capital. There has been a strong undercurrent of alternative practices that have consistently remained more or less disconnected from the “combined and uneven” process of globalisation. These may be the result of traditional pre-capitalist practices, interstitial pockets of anticapitalist resistance or non-capitalist responses to crises (which are weakened when growth is resumed), creating a tapestry of spaces that escape the logic of profit-driven growth-oriented market capitalism. In “A Postcapitalist Politics”, feminist economic geographers J.K. Gibson-Graham rely on ontological reframing, re-reading and creativity techniques to uncover and perform “diverse economies” in the pursuit of overcoming the dominant “capitalocentric” understanding of the world. They conceptualise the economy as an iceberg, with only the commodified spheres of wage labour, capitalist enterprises and market goods being visible, while it is the submerged, invisible part of non-commodified economies that ultimately keep the iceberg afloat. This vast, ambitious research agenda initiated by Gibson-Graham maps an entire alternative political economy, covering practices as diverse as squatting, caring, gifting and cooperatives. Rendering them visible, understanding their particularities and addressing their limitations can nurture a rich imagining of alternatives, and by extension, a fertile ground for the postcapitalist reconfiguration of the economy. This optimistic outlook raises inevitable questions about the strength, extent and pace of these practices in substituting their capitalist equivalents. While the existence of a diversity of non-capitalist practices may be uncontested, whether they constitute a viable autonomous “outside” that grows within the “cracks” (Holloway) remains to be seen. Chatterton and Pickerill point to the overlaps between “anti-, despite- and post- capitalist” (476), in the sense that such practices negotiate between the complementary positions of being “against, within and after capitalism” (488). While inhabiting all these positions at once is not necessarily a contradiction, but demonstrates rather the capacity to inhabit multiple temporalities at once, it does not necessarily lead to practices that will constitute the seed form of postcapitalism. Another way to name them would be para-capitalist, in that while they may exist alongside capitalism, they have no influence over it.

Acknowledging the relatively benign and co-optable nature of existing non-capitalist practices, perhaps postcapitalism cannot be expected to emerge solely from the margins. Instead, another approach would be to seek signs for the Exit at the very core of late capitalism. This expectation stems from the belief that capital has become incapable of propelling societies forward, and that it holds back (social, technological, environmental) advancements to secure its self-preservation. This attitude echoes Gorz’s word choice of “surpassing”, and the same sense is conveyed by Jeremy Rifkin, another contemporary author speculating on postcapitalism (and hardly a radical figure), who writes about “the eclipse of capitalism”. Several ecological metaphors may be comparable in their tone. Recent slogans have expressed a desire to “overgrow” or to “compost” capitalism, and the striking commonality of all these expressions is the assumption that the transition ought to be organic and inescapable. Rifkin is particularly confident about the future. He does not hesitate to declare that by the middle of the century, capitalism “will no longer exclusively define the economic agenda for civilization” (21) and, whether we like it or not, will be replaced by what he calls the Collaborative Commons by mid-century “as the primary arbiter of economic life in most of the world” (2). Others are as certain about the outlook, while being less interested in the nomenclature. Gus Speth avoids the question altogether by stating “whether this something new is beyond capitalism or is a reinvented capitalism is largely definitional” (11). Such indifference is revealing, in that if one expects such change to be inevitable, incremental and non-confrontational, it could indeed be named anything out of convenience (the present-day denomination of “Chinese communism” or “Western democracies” could attest to this). On the other hand, if it is an intentional and oppositional project aimed at making a clear break from the past, then it would legitimately distance itself from capitalism. Climate urgency and impacts aside, there are plenty of other reasons for doubting the possibility of a smooth, self-actualising transition; if anything, the vacuum left behind the disintegration of the global order can easily be filled by rising reactionary forces. A deliberate postcapitalism would go beyond the observation of prefigurative impulses and build a coherent political project around them.

While postcapitalism may be a general name applied to the cultural, social and economic practices that have relative autonomy from capital, the point is not merely to delineate what lies outside or at the periphery of the commodity-machine, but rather to consider these practices as part of a political project that seeks a systemic transition away from capitalism. Neither satisfied by the diverse economies of Gibson-Graham, nor convinced by the “inevitable outcome” optimism of more recent authors, Srnicek and Williams put forward a distinct strategic vision for postcapitalism, complemented by a (rather polemical) critique of what they label “folk politics”, taking the form of the horizontalist, localist and immediatist tendencies that are predominant in recent social movements and sustainability initiatives. They argue that “any postcapitalist project will require an ambitious, abstract, mediated, complex and global approach -- one that folk-political approaches are incapable of providing” (chap.1). They put forward a position that (re)embraces a universalist, intentional and counter-hegemonic project as the path to exit capitalism. They unambiguously advocate the building of a new world “not on the ruins of the old, but on the most advanced elements of the present”, suggesting that the existing capitalist infrastructure “can and will be reprogrammed and reformatted towards post-capitalist ends”. Their Accelerationist Manifesto appeals to those situated inside, and that even benefit from late capitalism, and yet want to surpass it by unleashing latent potentialities: “the material platform of neoliberalism does not need to be destroyed. It needs to be repurposed towards common ends. The existing infrastructure is not a capitalist stage to be smashed, but a springboard to launch towards post-capitalism” (Williams and Srnicek 355). Standing in stark contrast to prevalent anticapitalist rhetoric, but having equally high expectations, the left-accelerationist project consists mainly of a series of populist and transitory demands formulated in such a way that they resemble the Gorzian non-reformist reforms. It is nonetheless possible to extend their willingness to repurpose (or hack) the capitalist infrastructure and to adapt that insight to this research. Can something as essential to capitalism as the design of commodities be the breeding ground of its transcendence?

Discussing another recent approach to postcapitalism will bring this interrogation closer to design and the political implications. A recent and outspoken advocate of postcapitalism, Paul Mason synthesises several of the previous positions. He is doubtful of the “forced-march techniques” aimed at the abolition capitalism, believing that the way out is “by creating something more dynamic” in its place (chap.Introduction). He considers the current economy to be incoherent, ambiguous and hybrid, containing complementary and conflictual elements, and “an incomplete transition, not a finished model” (chap.5) requiring concerted efforts to direct it towards postcapitalism. He appreciates existing practices as a “process emerging spontaneously” that needs to be supercharged – ”the challenge is to turn these insights into a project” (chap.10). He goes even further than previous positions, as encapsulated in the following statement:

While Mason’s emphasis on models and projects already implies design in the broader sense, here, he explicitly embraces a designer’s attitude to postcapitalist politics. Designing the transition suggests something other than developing an integrated “master plan” of the future, involving the deployment of strategic interventions in the present to resolve the problems of the transitional economy. Neither simply desiring nor observing postcapitalism, designing the means of transition tends to dissolve the tension between speculation and prefiguration. If design can be both prefigurative and speculative, then postcapitalism can indeed be designed, and the means and the ends of the transition reconciled. This raises two questions, however: what makes a practice postcapitalist other than being broadly “alternative”, and does such a distinction also apply specifically to design practices? Having so far established postcapitalist discourses and practices at large, the final section of this chapter will provide a specific outline of how postcapitalist design can be theorised and practiced.

In the previous section, I defined what constitutes existing alternative practices at large, and identified some conditions for their proliferation and their potential in unravelling capitalist relations. I will now seek ways of expanding and specifying these definitions to include also design practices. Those that are relatively autonomous from the market can certainly serve as a starting point for determining what already exists, however a consistent analytical model is needed to distinguish them from their capitalist counterparts. Branka Ćurčić succinctly poses a question in a similar vein:

Here, Ćurčić rightly defines the politicization of design practices as an engagement in the creation of more humane social relations, and I could add by extension, less commodified relations. Unlike greening commodities, this requires attentiveness to the kind of activities, processes and values with which one engages in design practices. So far, I have described this politicisation broadly as postcapitalism, defined in negation to capital, and denoting only its absence. An affirmative project requires an analytical lens, a vocabulary and an imagination that can provide an appropriate replacement for the complexity of commodified relations with “more humane” equivalents.

In the recent decades, the term “commons” has gained prominence in academic and activist debates as a general name for such alternative forms, without being reductionist in regard to their diversity – a counter-totality. Commons are the opposite of commodities; if the latter are goods that circulate on the basis of exchange, the former are goods that are available for sharing. It is worth noting that while the critique of commodities and commodification is well established in Marxist literature, theorisations on the commons remained a rarity until recently.[1] Following the symmetrical (if not simplistic) opposition of commons and commodities, the commons are collective goods that are distinct from (state-controlled, impersonal) public goods and (market-based, individual) private goods. Depending on the scope, angle or intent, there may be as many categories as there are commons scholars, and such distinctions may be useful, in that all require slightly different analytical models and political strategies. My goal here is neither to pit them against each another, nor to deny the wisdom they all contain; instead, by providing another categorisation, I intend to highlight the fields that have not yet been subject to a commons-centric analysis.

The commons have been conventionally conceived in two opposing categories, being the defence of natural commons (land, resources) and the proliferation of cultural commons (language, knowledge). In the words of P.M., these commons correspond to access to “bites”, as in food or fuels, and “bytes” as in digital information: “it’s all about potatoes and computers” (17). While this polarity is in itself lucid and instructive, it does no justice to the commons that fall beyond the strict categories of the goods and resources defined by property relations. Silke Helfrich claims that this distinction is an artificial one, since all natural commons require the necessary knowledge to manage them, and all cultural commons depend on natural resources: “The common denominator among commons is that each one is first and foremost a social commons – a social process” (qtd. in P2P Foundation 6). Elsewhere she provides another useful distinction: “Our economy must not just be commons-based but commons-creating” (Helfrich). Combining both observations, I put forward a spectrum that ranges from predominantly material to predominantly immaterial commons sets on one axis, and the distinction between productive (commons-creating) and reproductive (commons-based) labour on the other axis. While natural and digital commons have already been mentioned, the social reproduction of care work could benefit from the same commons-centric analysis. Equally missing from the general understanding of the commons is the production of physical goods, which depends both on the reproduction of natural resources and the production of design knowledge, and my interest lies primarily in this quadrant:

Table 3. Commoning in four quadrants [2]

Elinor Ostrom’s life-long dedication to the study of an uncountable variety of commons around the world makes her arguably the most consequential contributor to the theorisation of the commons. Her conceptual innovation conceives the commons as “institutions for collective action” and governance, by commoners who regulate and manage the commons in non-hierarchical and non-coercive ways of self-organisation, thus setting the commons distinctly apart from state and market institutions. Ostrom’s design principles for successful, long-enduring commons (90), left a lasting mark on commons scholarship – one with an increasingly more relational understanding of the commons. If there is a constant in the infinite variety of commons, it is neither the existence of (material or immaterial) resources, nor is it the existence of (formal or informal) rules, but rather people forming an intentional community. But what do people, as commoners, really do in common? They “common”. Describing the activity or practice of commoners with the verb “commoning” is a relatively recent linguistic and conceptual breakthrough.[3] There are two intertwined meanings to commoning. The first one, closer to previous definitions, can be understood as “doing in common”, that is, to make, create or produce commons, or to put it differently, to produce shared value rather than exchange value. The second meaning is “managing in common“, in the sense of maintaining, administering and governing a resource or an institution as a commons. The distinction may be expressed as the etymological difference between collaboration (to labour together) and cooperation (to operate together). These two meanings are indistinguishable at the very definition of commoning, whereas they are considered entirely separate activities in industrial capitalism (leadership and base, management and execution, design and manufacture). Additionally, a third meaning to commoning is “holding in common“: reversing enclosures, i.e., putting into shared hands that which was previously commodified. This meaning of commoning is still distinct from communisation, which suggests the abolition of private property through the expropriation of land, factories or infrastructure, and rather modestly implies a “voluntary” pooling of private assets as a commons. In other words, goods or resources that may have come into being as commodities or private property can still have a “second life” as commons if the institutional configurations allowing their mutually beneficial sharing are available for adoption.

Summarising these definitions, commoners self-organise and self-govern their collectivised labour practices in institutions of collective action, while commoning signifies this shared value creation that results from the combined activities of the production and reproduction of resources as commons. These definitions of commons and commoning have the potential to demystify what the more general terms “alternative” or “diverse” are unable to explain, and their specificity allows an understanding of the capacity of commons to overcome, outsmart and disrupt their market counterparts. Just as the commodity-machine is not a static property relation between subjects and objects, but rather a dynamic of commodification of relations, commoning is also to be thought as a (re)productive social process that extends the non-commodified sphere, shrinking the flux of capital, and expanding the flux of commons. De Angelis generalises this: “commoning is the life activity through which commonwealth is reproduced, extended and comes to serve as the basis for a new cycle of commons (re)production, and through which social relations among commoners – including the rules of a governance system –are constituted and reproduced” (201). Adopting a broader perspective, separate instances of commoning activities appear to build up towards commons systems that mutually support, proliferate and reinforce each other. For the (post-)Marxist scholars associated with the Midnight Notes Collective, this insight goes beyond the historical and contemporary analysis of the commons, becoming a strategic vision for a political project to build counter-power (Caffentzis and Federici). If the commons are potentially a social force that resists and counters capitalist valorisation, what is needed is both vigilance, to avoid the risk of co-optation and capitalist capture, and a programmatic willingness to replicate, expand and accelerate commoning with greater ambitions. Dyer-Witheford proposes a quasi-symmetrical analogy between the commodity and the common as the cell form of capitalism and “commonism”, respectively: “If capitalism presents itself as an immense heap of commodities, ‘commonism’ is a multiplication of commons” (‘Circulation’). He notes elsewhere that “this is a concept of the common that is not defensive (...) Rather it is aggressive and expansive: proliferating, self-strengthening and diversifying. It is also a concept of heterogeneous collectivity, built from multiple forms of a shared logic, a commons of singularities. (...) It is through the linkages and bootstrapped expansions of these commons that commonism emerges” ('Commonism' 111). Put differently, a commonist horizon – the systematic replacement of commodified relations by socialised ones – materialises in the construction of “complex and composite forms” ('Circulation') by combining and integrating already existing practices of commoning.

Having outlined what commons are, what commoning does and what commonism strives for, I can now propose some commoning practices that are applicable to design. A straightforward yet simplistic expectation would be to look at and to strive towards “common goods”, as objects with shared ownership. This, however, would not only be limited to a number of collaborative consumption cases, but it would also not be the normative claim that I would like to make. I am not concerned with the private ownership and use of most things (even a commonist would like keep some pairs of socks without having to communalise them). Instead of challenging the private ownership of raw materials and consumer goods – which, in any case, would fall outside the scope of design studies – my interest lies in the qualities of value processes within the reach of design practices. As a guiding interrogation, it is possible to rephrase the questions of Michael Hardt regarding the role of the artist:

As will be detailed extensively in the following chapters, I organise my answers along the three stages of shared valorisation in design. Chapter Two on peer designing focuses on the labour of designers. How does commoning (in the sense of the creation of shared value) transform the design process, and how does a designer become a commoner? In what ways are design skills, tasks and decision-making redistributed, and to what extent are autonomy and authorship maintained? Beyond the collaborations between professional designers and the participation of users within the design process, the most distinctive commoning practice is peer production, or “the ability to create value in common” (Bauwens, “Designing” 53). How is peer production deployed in design projects and how do they become apparent in the designs? To what extent do peer designing practices happen outside competitive markets and call for new ways of valorising design work? I inquire whether the organisation of work in novel cooperative and democratic forms offers workers a better deal than exploitative wage labour and precarious self-employment.

Chapter Three on open blueprints closely investigates a second valorisation process, being the commoning (in the sense of shared governance) of design projects themselves. Influenced by the emergence of technologies that facilitate the sharing of information and the spread of cultural goods through peer-to-peer networks, digital commons have been flourishing. The opportunities provided by the open/free/public circulation of knowledge are stifled by the rent extractivism of the predominant intellectual property rights regimes, although Gorz, Rifkin and many others argue that knowledge, being digitally reproducible and therefore abundant, tends towards becoming common property. Commoners in peer production both rely on those resources as input, and return their output to the public domain (open-source, copyleft, creative commons). In other words, the practical knowledge of building the commons is produced (developed) and reproduced (shared) by a community. What are the economic and social dynamics behind the free sharing of design knowledge? What open-sourcing strategies are employed effectively? To what extent do such strategies generate meaningful engagement by designers, makers and users? The extent to which open blueprints need institutional arrangements to sustain their longevity needs to be investigated.

Chapter Four on maker machines studies the commoning (in the sense of sharing as commons) of design artefacts. More specifically, my interested is in tools and machines as tangible means of production that are developed by makers and put into use by productive communities. What motivates and guides the development of such maker machines, and what qualities and aesthetics emerge? The practices I study are “counter-industrial” in the sense that they testify to a shared vision on the right to access localised, distributed and self-produced means of production (instead of, for instance, taking over the existing industrial infrastructure). I question the implications of liberating, self-creating and democratising productive capacities, for resilience, autonomy and abundance. Design scholars Franz and Elzenbaumer provide a final set of questions, directed at designers interested in commoning practices:

These interrogations will be useful in an evaluation of the validity of this framework, and for the identification of blind spots that may remain beyond the scope of this research. Undeniably, design, commoning and postcapitalism are concepts and concerns of Western origin, and thus are not exactly universalisable. While my interest in these concepts is firmly rooted in the (self-)critique of Western thought and way of life, they may not immediately be relevant for, compatible with or beneficial to non-Western cosmologies. Encouragingly, more recent works intersecting design and decolonial thought raise similar interrogations and offer some striking perspectives of the coming transition (Escobar 46). As the following chapters will testify, there is a remarkable open-endedness and cross-pollination potential that can be fostered by postcapitalist design within the many worlds that inhabit this planet.

[1] In recent years the term has been adopted and popularised broadly by commons scholars: Linebaugh, Pasquinelli, Hardt & Negri, Dardot & Laval, Bollier & Helfrich, Rifkin, Stavrides, De Angelis, Federici, Dockx & Gielen.

[2] A comparable typology is developed also by Wim Reygaert (Bauwens and Onzia).

[3] It is possible to encounter “commoning” both in historical and contemporary sources, but its theoretical substance was created by the Marxist historian Peter Linebaugh (Magna Carta; Stop, Thief!).

Built with Mobirise page creator