Fig. 16. The Growroom, by Husum&Lindholm for Space10

In recent years, openness has become an increasingly vague, catch-all metaphor to describe the emergent political, economic and cultural counter-trends against the predominant regimes of intellectual property, enclosures and privatisations. As the example of OpenDesk testifies, openness has substantial implications for design practices, as a strategy to promote the circulation of blueprints in the absence of market mediation. Before bringing in and problematising other design examples, it is essential to define openness in the broader cultural context. The history of open-source and free software is particularly relevant as a precedent and source of inspiration for the conceptualisation and shaping of the meaning of open design principles. Considered as the predecessor to what is now implied by “open”, parallels are to be drawn through the different meanings ascribed to “free”. Inspired by Roosevelt’s original “Four Freedoms”, free software pioneer Richard Stallman proposed equivalent freedoms for software in the 1980s, being to run, to study, to redistribute and to improve the source code. Even though free software is intended to be free as in “free speech” (denoting no restrictions) as opposed to “free beer” (meaning at no cost), this can be considered a simplistic opposition. It is suggested that it may be more accurate to think of “free as in puppies” – it may carry no initial costs, but it still comes with the responsibility of caretaking. Borrowing from other languages, “libre” and “gratis” have been introduced in an effort to remove any linguistic ambiguities and to better differentiate the terminology. For better or worse, the term “free software” came to be eclipsed by “open-source” (coined originally by Christine Peterson), and the open-source Initiative was founded in 1998. Proponents of free software remained critical of open-source, distinguishing the former as an idealist political movement, and the latter a pragmatic development model. To better understand the meanings and implications of open-source, I follow the outline provided by Open Access scholars Pomerantz and Peek, in their broad and meticulous essay entitled, somewhat fittingly, “Fifty Shades of Open”, reviewing the uses of the concept:

With so many meanings, openness can be a blessing as much as a curse. However, in the true spirit of openness, the authors resist the temptation to pit meanings against each other or to suggest a hierarchy between them. Instead, they acknowledge that openness itself is open to interpretation, and that there is an open invitation to reappropriate its meaning. Inspired by the Free Software Foundation’s General Public License, but extending the Copyleft (opposite of Copyright) regimes beyond software, an impressive constellation of licences with differentiated legal frameworks have emerged. Most notably, Creative Commons (CC) provides various rights and protections to the producers, distributors and users of raw data, creative works, technical inventions, or any type of cultural artefact or knowledge base. CC liberates the “display, performance, reproduction, distribution” of the content while reserving “some rights”, and various combinations of “attribution, non-commercial, share-alike and no-derivatives” specifications fragment the simplistic binary of “intellectual property” versus “public domain”. While becoming increasingly popular, CC also has its detractors. Kleiner considers CC to be merely a more permissive subset of copyright, labelling it “Copyjustright”. He is also critical of Copyleft, since it indiscriminately allows capitalists to free-ride the commons, putting forward a counterproposal in the form of “Copyfarleft”, in which there is “one set of rules for those who are working within the context of workers’ communal ownership, and another for those who employ private property and wage labor in production” (Kleiner 42). Inspired by this principle, the Peer Production Licence (or Copyfair) has been developed, providing free access to commons-producing entities (such as commoners, cooperatives and nonprofits), while charging fees to commercial, for-profit companies that would like to benefit from the same goods and services (44–49). This is so far the most relevant licensing tool available for postcapitalist use, since it generates and retains value within the commons.

Principles of openness have been adopted in a wide range of cultural practices, but with particularities in each domain. The similarities and differences between software development and product design are striking: both depend on some kind of “source” material (code for software, blueprints for hardware), but while digital software is frictionless and reproducible, physical hardware is much less so. While what is meant by “open-source hardware” here is mainly electronics, and by extension, it is applicable to any hardware, tool or machine under the general name of Open Design (Abel et al.). Minimally, it denotes that blueprints are available through one of the licences mentioned above, which is “only valuable in the short term” (Pomerantz and Peek). Other open design principles go much further than merely lifting the intellectual property rights of a design, and engage rather in long-term strategies. In a broader sense, designing for openness entails the creation of a community around a product seeking active contributions from users, designers and makers. As we have already seen with OpenDesk, this is not necessarily incompatible with market practices, in that it presents rather a novel approach that goes beyond simple producer-to-consumer relations. Designing for openness therefore means, first of all, designing from scratch, with considerations of how it can be manufactured easily, followed by the release of the blueprints and documentation for broad circulation, and finally facilitating a community that will maintain and improve the project. Not all projects fit this extended definition, with some questionable claims of openness having been labelled “open-washing”, as coined by Michelle Thorne, or “fauxpensource” by others (Masson). False claims are relatively easy to identify in software, but it can be difficult to identify what could be considered open-washing in product design. I present two examples below to provide a sense of the range of practices that are up for debate as to whether they constitute an abuse of the term, or are acceptable shortcomings from an idealised definition.

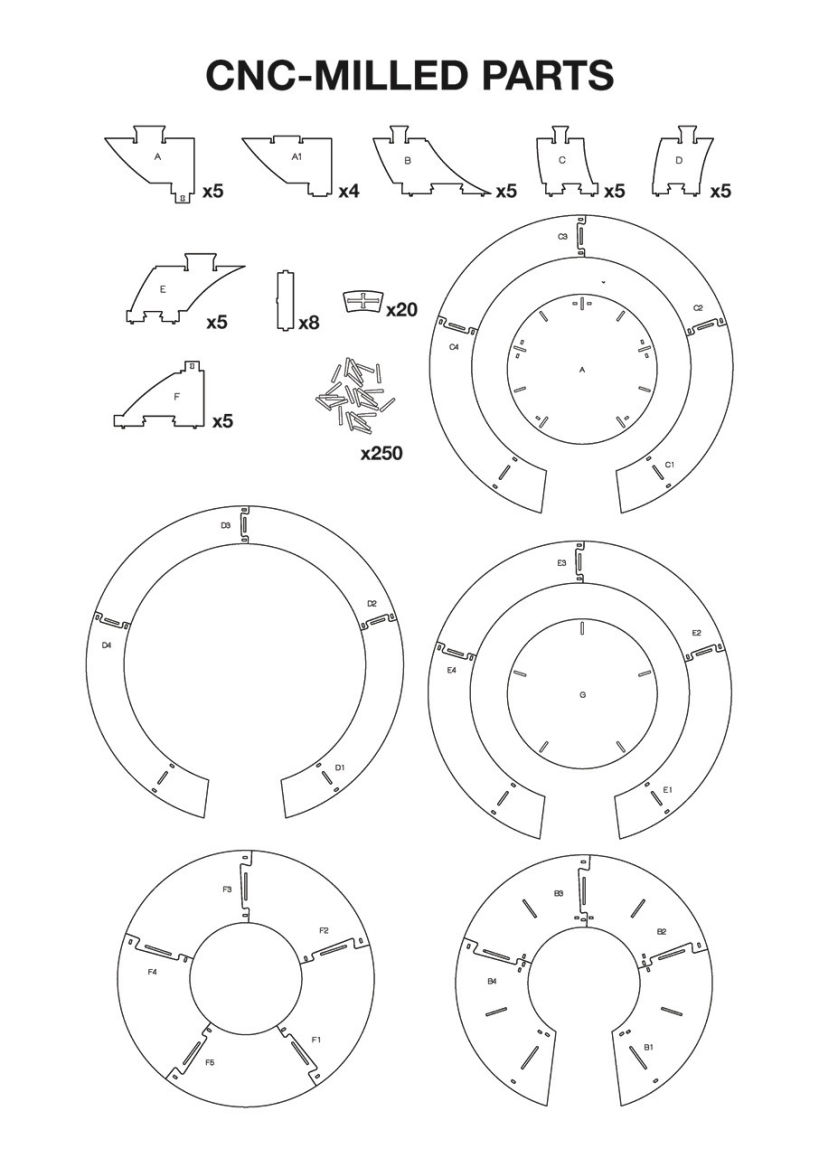

The first case is The GrowRoom, started as a collaboration between Space10 – IKEA’s external research and design lab dedicated to “future living” – and Danish architects Sine Lindholm and Mads-Ulrik Husum. Originally conceived as an “artistic exploration” of urban farming, The GrowRoom is a spherical pavilion and a vertical garden, made of multiple layers of stacked plant beds occupying a small footprint. [fig. 16] A few months after exhibiting a prototype at the CHART Art and Design Fair in 2016, an easier to build and more affordable version of The GrowRoom was released on GitHub as open blueprints, “to encourage people to develop their own urban growing projects” (IKEA Museum). The reasoning behind this was explained as follows:

To put it more simply, the multinational furniture-maker commissioned a design to address a sustainability challenge, and recognising that commercialising the flat-pack kit through its global production chain would be self-contradictory (if not counter-productive), it chose to release it instead non-commercially for local production. This is remarkably close to the design principles and ethos of OpenDesk (as well as WikiHouse, presented in the next sections), and could also be seen as a remarkable volte-face and an honest admission that only a postcapitalist approach is an appropriate solution, even though there is no indication that the project was intended for the market to begin with. Some might dismiss this yet as another case of greenwashing, since the exquisite pavilion remains a rather costly solution to urban farming. I am still tempted to consider The GrowRoom as compelling, rather than dismissing it as a mere PR exercise, due to the multiple independent replications documented and shared online. Since the design is open, the interest of the recipients in reproducing it has far more significance than the original intent. Following the positive reception received by The GrowRoom, Husum and Lindholm developed a new iteration of their concept with GrowMore, this time creating a modular system made of only six basic elements that can be repeated and bolted in a variety of combinations. [fig. 17] As seen in the previous chapter, modularity enhances one’s ability to adapt, hack or fork the project, as a context-specific application of the pavilion-wall is more suitable than a rigid, perfect sphere. It was more than fitting that GrowMore was first showcased at the 2017 Seoul Biennale entitled “Imminent Commons”, as part of a thematic exhibition dedicated to urban, ecological and technological commons. That said, while the designers had expressed their commitment to “sharing the drawings of the design open-source (…) to participate in, and enhance, the local production and maker movement” (Lee and Anderson), this has not yet materialised. In a personal communication, the designers promised that the drawings would be open-sourced in summer 2020.

The other case is the 2014 pledge by Tesla Motors to apply “the open-source philosophy” to its patents, and not to “initiate patent lawsuits against anyone who, in good faith, wants to use [its] technology” (Musk). The reasoning behind Tesla’s decision was that its main competitors were not other electric car makers, but the big car companies with a vested interest in perpetuating a predominantly hydrocarbon-based automotive industry. In other words, choosing not to sue other EV manufacturers that make use of the technologies developed by Tesla is actually beneficial for the company, in that it would eventually beat its main competitors by becoming the electric car standard beyond its direct market reach. However, as is the case with many of the PR moves of Tesla, the devil is in the details. The provision of “acting in good faith” is rather open to interpretation, and determining what counts as “bad faith” is left to Tesla alone. For instance, if a company that makes use of these patents enters into direct competition with Tesla, or that indirectly affects its business negatively, it is entirely Tesla’s prerogative to enforce compensation. So far, there has been only one company, a Chinese startup, that has made use of Tesla’s patents (Lambert). Once again, it is worth resisting the temptation to dismiss Tesla’s move altogether as a masterful combination of greenwashing and open-washing, and to consider it along the lines of IKEA’s involvement in The GrowRoom[1]. However incomplete or imperfect they may be, only moves towards postcapitalist business models are consistent with the sustainability objectives. With this in mind, I can now look at WikiHouse, the original project from which OpenDesk derives. Thinking larger than furniture, WikiHouse is an ambitious, long-term project that is still in its early stages. Various facets of WikiHouse are to be analysed as distinct objects of study, with the first constituent elements being the structure and the content of the platform (which at the time of this research consisted of a file depository for projects in-development), the established design principles that guide the project, and the current downloadable design blueprints and the associated licenses. Next to these, the second element to be analysed is the WikiHouse Foundation itself – the non-profit “custodian” entity that administers the design commons. It is defined and regulated by its “Constitution”, being a collaborative document that determines the structure, principles and goals of the project, as well as the “roadmap” of its future development. The elements that are nested into each other will be revealed progressively in the following sections.

[1] There will be a similar anecdote given in the next chapter involving Phonebloks and the then-Google owned Motorola.

If a wiki is a “website on which users collaboratively modify content and structure” (Wikipedia), then a WikiHouse would be a house that would permit the collaborative modification of its design by its users. While this transposition may be somewhat accurate, the actual project offers many more definitions. According to its initiators, it is not meant to be a single house, but “an open-source building system (…) to design, print and assemble beautiful, low-energy homes, customised to their needs” (WH, Open). Elsewhere described as a “global design commons” (WH, Project) for sustainable homes and neighbourhoods, the project merits extensive analysis in order to interrogate its claims on both commons and sustainability – two core characteristics of postcapitalist design practices. By almost consistently avoiding the word “architecture” in favour of more generic terms such as construction system, WikiHouse positions itself more in affinity with the projects in this study than standalone architectural works. It claims to be “not just one design, or even one technology, but a way of working; a set of principles” (WH, About). These provide an early indication that the main activity of WikiHouse is not to produce blueprints, but to maintain an open platform, being the infrastructure that sustains the development of the entire project. My focus on this section is on the design principles and the practicalities of accessing the blueprints, while the institutional arrangements are to be considered separately in the following section.

The origins of WikiHouse date to the summer of 2011, when curator Beatrice Galilee invited Architecture 00 to the 4th Gwangju Design Biennale in South Korea (WH, Foundation). Zero Zero brings together designers, programmers and social scientists, claiming to “operate an open business model” that includes professional architecture services, the WikiHouse and OpenDesk projects, and other initiatives (Project00). Interest in the WikiHouse project had been raised several months before the exhibition, when science-fiction writer Bruce Sterling—hardly the most kind-hearted critique—blogged an enthusiastic endorsement on the Wired website. His brief comment was both optimistic and personal (“I could quite likely build and inhabit [one]”), and gloomy and pragmatic (“The ideal Favela Chic domicile for areas wracked by climate change”). Appealing to a wide range of audiences, his comment triggered early viral interest, and this interest remains to this day both a blessing and a burden—the failure to deliver the hyped promises before interest wanes away in disappointment (called “vapourware”) puts the credibility of the developers of the project at risk. The initiators of the project admit that “hardware development was driven by a sequence of small exhibition prototypes and events” since the Biennale, and that after four years, “WikiHouse is finally about to ‘reach the start line’” (WH, Where). Such a slow pace to start a project could be considered a failure in engaging many people instantly, which would have permitted rapid scaling. Yet it could also be seen as an intended strategy to lay firm foundations for a long-term engagement rather than merely being the first to capture an emerging trend in design and technology.

A building system—particularly one that is developed collaboratively —requires a set of rules or broad guidelines on how every component or module fits into the whole structure. For OpenStructures, in the previous chapter, this was the OS Grid, while for WikiHouse, it started with the “Design Principles” that are incorporated into the Constitution. The first principle urges the sharing of information globally, but the manufacture of goods locally, citing the “recipes and biscuits” quip attributed to Keynes. The second principle, this time in the form of a quote by the open-source pioneer Linus Torvalds, advises us to “be lazy like a fox” – implying that instead of reinventing the wheel or starting from scratch, it is better to build upon the work done previously by others (with due credit and proper licensing). Another principle is to “start somewhere” near oneself – that is, instead of attempting or pretending to resolve other people’s problems, designing for one’s own needs and then sharing the results, which may be more helpful to others. At the same time, designs are supposed to be safe, inclusive and with low thresholds of participation in terms of time, cost, skill, energy and resources. Similarly, the Japanese “poka-yoke” principle of designing mistake-proof modules is meant to make the assembly process more accessible and safer. In practice, it means never designing a piece that cannot be lifted by a single person, or making sure that pieces cannot be put in the wrong place. Similar to OpenStructures, other principles include opting for open materials, open standards and modular systems, so that everything is designed for disassembly and circularity.

If the Principles are instructions on how to design, then the Release Notes are instructions on how to build. The “WikiHouse Chassis System Version 4.2.1 — A Guide for Designers” is a document that provides the closest contact with the intricacies of the project. A previous version (v3.0) expresses that “eventually a design guide should become unnecessary”, although this expectation is somewhat ambiguous, in that it suggests that one day the blueprint itself will be so self-explanatory that no additional documentation will be needed. However, currently the only way to acquire all the available knowledge on WikiHouse is through booking a workshop with a member of the Foundation—and not the freely available guide itself. There is a delicate balance between providing too much information, which would intimidate beginners and set the learning threshold too high, and relying more on human contact and social relations than documents, which builds communities rather than promoting strictly self-replicating information. An assistive teaching role demands a time and space where the dissemination of knowledge can take place, while a document that is available anywhere and at anytime is less likely to be picked up. Additionally, such workshops also create livelihoods for the developers, who thus do not rely on the sale of licenses or products. Ultimately, the daunting and equally formidable task of building a house generates such a body of knowledge that may be hard to capture in documentation, let alone transmitted one-on-one.

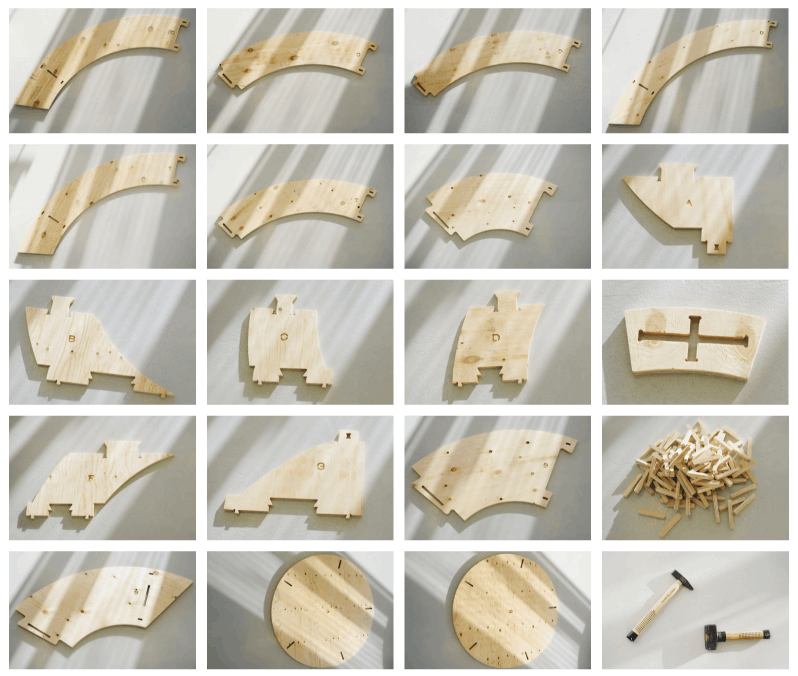

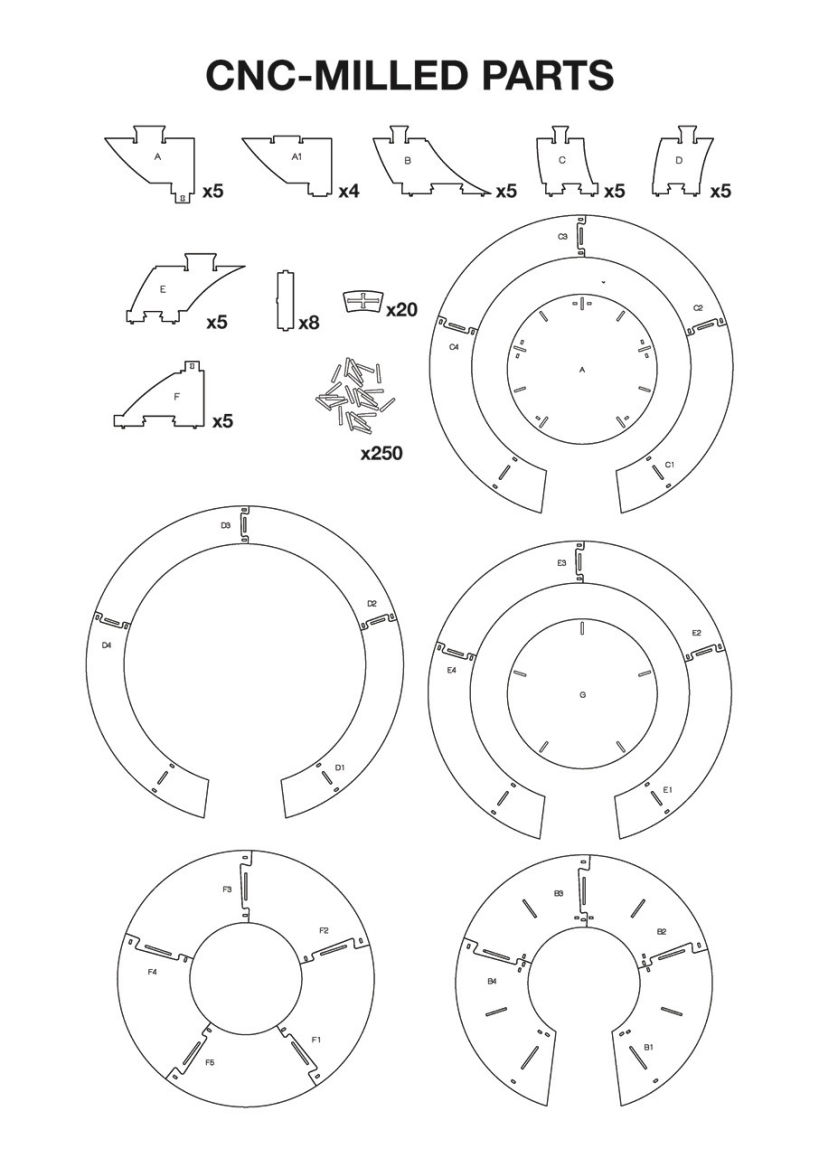

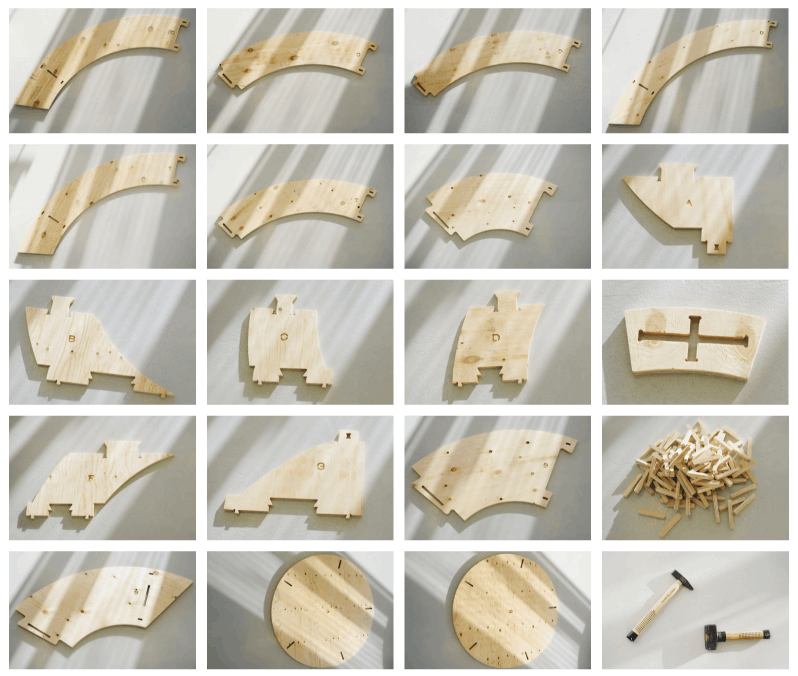

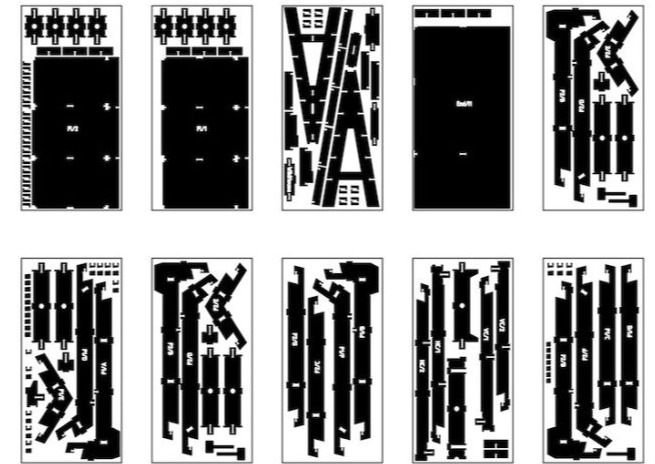

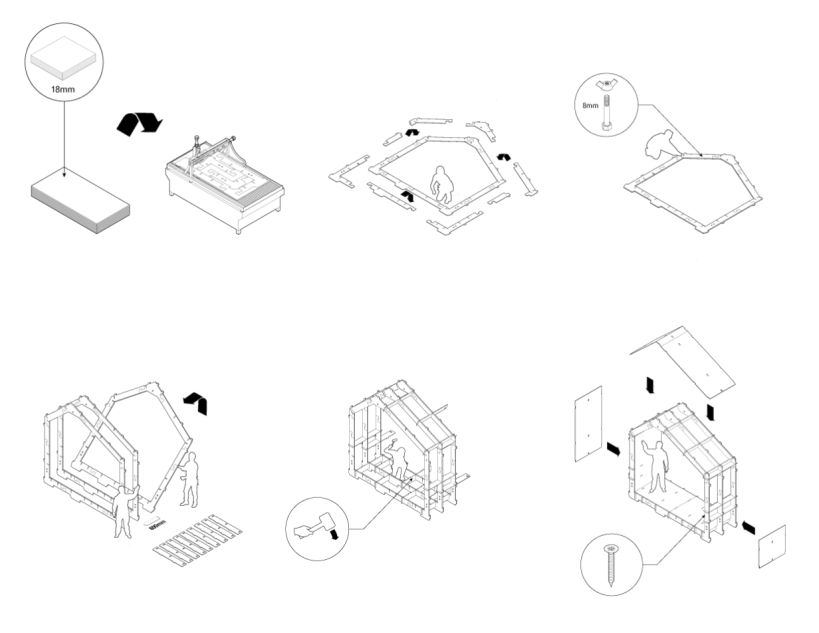

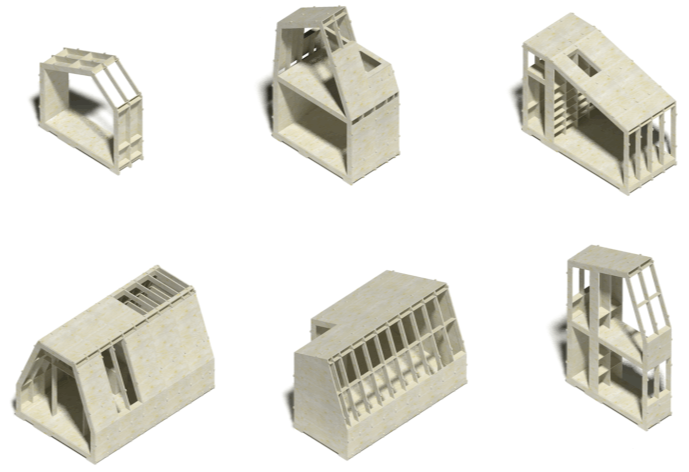

The design guide is introduced with three considerations; the foundation requirements; the general shape and size of the building; and the exact location of such openings as doors and windows. These factors are location-specific, and are to be determined for each building, while the chassis system itself adapts parametrically to each setting. What is standard to every WikiHouse is the “repetitive grammar of 300 mm long Lego-like” structural plywood modules, which, in combination with spacers and reinforcers, make up the box frames. [fig. 18] These are the essential elements – CNC-cut from structural plywood sheets, repeating by default every 1.2 m – which are raised and attached to each other with connectors and panels. In this assemblage of standard and custom parts, each piece is carved with a code name, indicating the section of the frame to which it belongs. In this way, no part can be mixed up with another, and the whole naming system “can be understood like a DNA chain along the house: A, A, B, B, A”. In the assembly process, some joints are slotted and pegged together, others are “persuaded” into position with a mallet, but no screw or glue is necessary to hold the structure together. [fig. 19] For the fine tuning of tolerances, the design guide encourages starting with the manufacture of a “Step Up / Test Piece” —both a simple stepping platform, and a small object to test and tweak how loose or tight all the joint types of the WikiHouse fit together. The mallets (referred to euphemistically as “persuaders” in the documentation) can be made from the same material and using the same machines, alluding to the self-production of the means of production.

The entire project resides in an online file repository of work-in-progress files, all shared under the CC-BY-SA licence. The WikiHouse Foundation provides an unambiguously named “WikiHouse Commons”, hosted in a shared Google Drive folder, containing presentations, manuals and 3D files, including design files, cost sheets, prototype photos and any other relevant documentation. The instructions for using the Commons encourage teams to “share by default” every file (WH, How to), instead of postponing until a perfected, final version is ready – unfinished works require critical engagement, and not taking anything for granted is a basis for creative contributions. Since openness is meant to encourage collaboration, the folder is structured with distinct sub-projects or forks. Access permissions to these sub-folders function similar to licenses, with everyone free to view (and therefore copy) the designs, but only trusted contributors being able to edit the originals. Previous versions of a project can also be retained in order to track its evolution, and to fork or re-visit elements from any point in time. These principles all appear sound and well, however, the reality seems to be less than ideal; other than the (00-led) “featured projects”, the folder entitled “all projects”, containing 350 subfolders, is mostly empty, indicating little activity, let alone collaboration.[1] In fact, the Google Drive folder was active only between 2015 and 2017, after which the database was migrated to the Github repository to take advantage of better versioning and forking. Since 2018, the WikiHouse website has stated only “files coming soon” for an upcoming beta version codenamed Blackbird. The choice to pull down incomplete files is explained as follows: “Although we always seek to publish files as early as possible under a clear disclaimer of warranty, because Blackbird contains some kinds of joint that are entirely new, we are testing the system in early pilot projects before publishing the files” (WH, Blackbird). The principle of “share by default” seems thus to have been abandoned in favour of a more conventional approach, and to only release major milestones.

Such limitations of the project can be encountered at various stages. For instance, all the documentation is “provided on an ‘as is’ basis”, that is to say, without any liability or guarantee (WH, Terms). As with all buildings, there is a legal obligation to consult an engineer, and even more so for the early prototypes of an experimental project. When manufacturing the pieces, the speed of the CNC routers can become a potential bottleneck. The design guide advises to expect approximately 5–6 sheets per m2 of floor area and 30 minutes per sheet, equating to 5 days of non-stop CNC cutting for the average floor area per person in Europe. If the fabrication takes place at or near the construction site, then the pieces can be assembled as the rest are being cut, reducing eventual delays and costs. Once the chassis is standing, additional layers, such as a breather membrane and insulation, are required, after which it can be cladded and fitted in various ways. The project’s ambition is to integrate the full catalogue of heating, energy, water, waste and connectivity solutions that will envelop the house. These are evidently very modest beginnings for an ambitious project that aims to reach out to 99 percent of the world population, as opposed to most of architecture destined to the 1 percent. A methodological question arises: is it simply too early to study this project? It is easy to discount a project that has barely started, let alone finished. Similarly, it would be unfair to conclude that this represents the failure of a project that is aware of its limitations, and that openly admits its “pre-launch” state. Open projects are, by definition, always too early to launch and are never really complete, and it is precisely the fact that they are premature and open-ended that makes them worthy of study. There is a need to navigate between their prefigurative and practical elements, as presented above, and their speculative potentials, which will be discussed in the following section.

[1] Similarly, while plenty of interest and enthusiasm were expressed in an earlier mailing list, few were taken to further stages of development. Recently, a more active Slack channel has been set up for collaborations.

Let’s take a step back for a moment and consider how we got here: driven by fossil fuels and finance capital, the industrial revolution meant that everything had to be redesigned from scratch, with the centralised, mass-manufacture of goods being the basic methodology. With the advent of Fordism, industrial capitalism promised unlimited access to consumer goods, seizing the opportunity to expand its markets. Modern design was a response to this new mode of production, and the drawing boards of designers and engineers came to reconfigure everyday lives, consumption habits and their own social role accordingly. This redirection proved to be successful in attaining the goal of democratising consumption in the West, although with devastating consequences, undermining the very basis of its aspirations. At the late-capitalist end of the globalised circuits of manufacture, information technologies are expected to unleash a new mode of production, one that corrects the mistakes of the industrial one. If such a transformation is underway, then everything must be redesigned, tapping into the latent potentials of digital reproduction and manufacturing techniques. Powered by the internet and other distributed tools, WikiHouse attempts to rise to the challenge, but this time addressing the pitfalls of the previous mode of production. In the words of its founder Alastair Parvin, “If design’s great project in the 20th century was the democratization of consumption (…) design’s great project in the 21st century is the democratization of production.” From one populist vision of design to another, this section appraises WikiHouse as an attempt to render design more accessible through the deployment of openness strategies.

One of the key documents of the WikiHouse Foundation is its Constitution, drafted first in 2015 by Alastair Parvin, and since then open to the public for suggestions as a Google document. Currently on version number 6.4, it contains several sections defining the Foundation, its structure and funding, its design principles, licences and trademark policies, and its development goals. Other than the general objectives of the Foundation, the management of various intellectual rights regimes warrants particular attention for the purposes of this chapter. The three main goals of the Foundation are:

These general objectives of the Foundation capture the core values of openness, by maintaining, circulating and producing open blueprints as commons. Not only does it pledge to remain open access forever, it actively pursues business models, sustainable livelihoods and community building to cultivate an open working system for everything. How knowledge is held in commons, how communities are supported and how development is promoted deserve a closer look, as this may elucidate the extent to which these goals are within reach.

In the case of WikiHouse, there are three distinct elements: the hardware, the software and the trademark. Since the software that enables the generation of the exact files is in the early stages of development, its licence is not very elaborate, stating only that it is open-sourced. The hardware on the other hand, consists of all the digital files and instructions required to produce WikiHouse structures, corresponding to the design blueprints conceptualised in this chapter. In an earlier phase of the project, these blueprints were available under a Creative Commons non-commercial licence, explicitly banning their professional, commercial use by designers, with the primary purpose stated as “having as a place to live, not as an asset to sell or rent” (WH, Design). While this appears to be true to the principles of commons, it creates an obstacle to its adoption and development. The newer Constitution specifies that both commercial and non-commercial uses are possible, as long as any derivative works carry the same license as the original, which “ensures that knowledge developed in commons remains there forever”. The power of open-source is explained as “once solved, each problem will always be solved for everyone, forever; and will continue to evolve as it is improved and adapted”. Similarly, Parvin notes that “once something’s in the commons, it will always be there”. Having a common solution to a problem eliminates any “reinventing the wheel”, saving time, energy and money for those who encounter the same problem again and again. An appeal for donations concludes the design guide with a grand claim: “we work for everyone”. Any contribution (monetary or otherwise) to an open-sourced project, unlocks potentials that cannot be restricted to a limited audience, thus actualising the problem-solving promise of more democratic designs than with CopyRent regimes. In other words, it generates value, and “if you have derived value from using the WikiHouse system”, the Foundation expects donations from the benefactors. Sharing value leads to shared value creation, and vice versa, and by extension, creating shared value leads to valorising sharing as such.

Remarkably, it is the WikiHouse trademark, comprising the name and the logo, that has the most elaborate protection scheme. At first, only the initiators of the project could legally claim to be WikiHouse – one could not call their structure a WikiHouse, even though it was possible to produce an identical design. This rather arbitrary principle of determining what constitutes a WikiHouse and what is ineligible has since been abandoned in favour of a more permissive policy. The trademark now states “may be used to discuss, attribute and describe the wider project and community” (WH, Terms). Accordingly, any team signing the WikiHouse trademark licence can now become a non-commercial WikiHouse Chapter and adopt the WikiHouse name, as well as a “community trademark badge” styled after the original logo. In the original logo, the house outline repeats and branches out in every direction, being the basis of a tangram-like composition for the derivative logos shaped after each country the Chapter is based in. [fig. 20] Further types of badges to be used by commercial WikiHouse “providers” are intended to be developed in the future, allowing designers, manufacturers, builders and certifiers to benefit from the visibility of the project and to provide complementary services to it.

The opening up and decentralisation towards WikiHouse chapters indicates a growing interest in the project. There are today more than a dozen local chapters, with the most prominent being WikiHouse UK (under project00), WikiHouseRIO (winner of funding from the TEDPrize), and WikiHouseNZ (awarded by the Sustainable Habitat Challenge). It is estimated that around 40 people work on WikiHouse projects as one of their primary occupations. In the earlier phases of the project, these groups were charged with developing any part or combination of the hardware, software or community platform that constituted the project. Moving forward, most chapters became networks of individuals and businesses, working in collaboration to develop WikiHouse-based projects. Since anyone has the right to fork the project to improve or adapt it, some chapters specialise in experimental pavilions, multi-storey structures or post-earthquake housing. While they are expected to operate autonomously, they are bound together by a common purpose: “what they share collectively forms the commons: assets created/owned by individual chapters which are published under open license” (WH, Where). Having such clarity in the purpose and principles that guide the project helps to expand it, giving not only stability to the project, but also credibility for the attraction of potential funders, volunteers and supporters. Most importantly, as the project matures and applications expand from tiny houses for leisure to commercially viable and larger housing complexes, partnerships also evolve, from hobbyists to professional collaborations, consolidating the base even further.

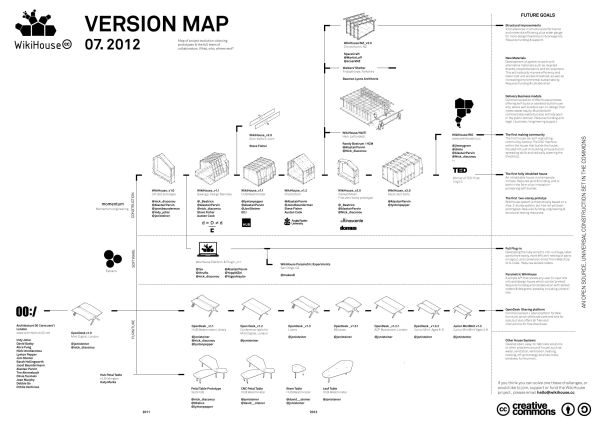

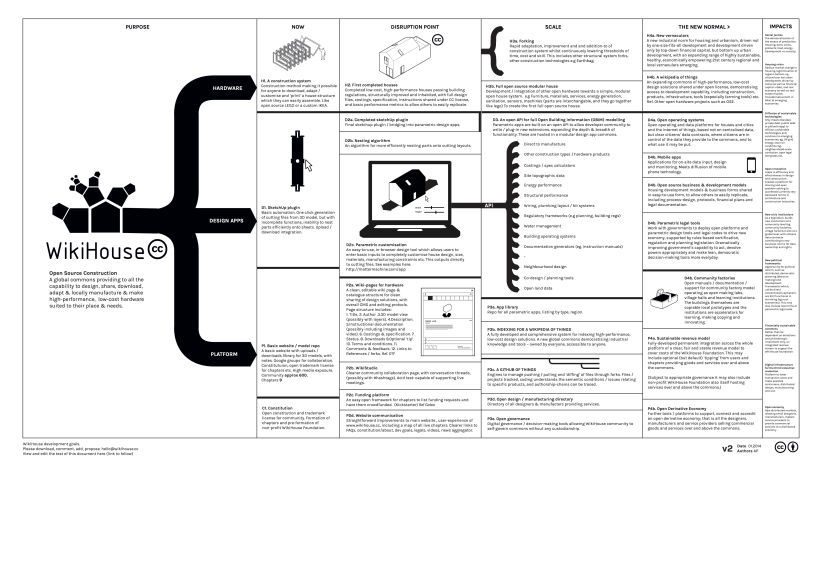

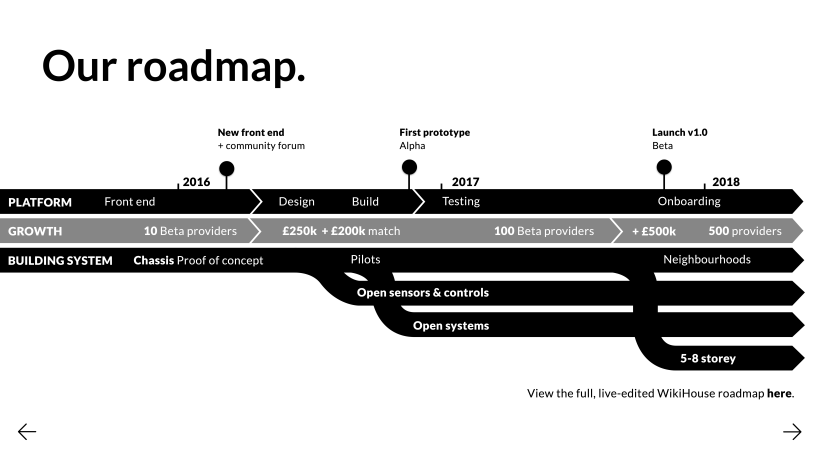

The final factor to take into account here is the project’s future roadmap. Longer term aspirations and speculations can tell as much as the prefigurative achievements or present-day institutional arrangements of the project. The WikiHouse Constitution states that the “project has no end destination, only a clear direction of travel”, and it is a conscious choice to strategise out in the open about where WikiHouse is headed, even though that direction may be constantly reevaluated and the map redrawn. There are documents that shed light on some potential futures: a Version Map (dated 2012), a Development Goals v2 (dated 2014) and a presentation (2016) all provide detailed descriptions of various tracks branching out of timeline diagrams. [fig. 21] I consider these documents squarely as works of speculative design fiction – they are not to be taken for granted as definitive or evaluated for their accuracy, but as expressions of desire and imagination – a wish-list for the future, and a compass to guide the project. The Development Goals divide the timeline into four main columns as projected stages of expanded influence, headed Now (what’s available at that stage); Disruption Point (mission-critical goals in the short term); Scale (impact to achieve in mid-term); and The New Normal (intended paradigm change on the horizon). The boxes meticulously describe various facets of the project:

These three divisions stand out as indispensable for postcapitalist design: a universal library in which to pool open blueprints; established norms and tools to maintain and govern this commonwealth of design knowledge; and a social and logistical infrastructure that supports the livelihoods of all the contributors. This triad is very much in line with the following note of caution: “the expectation that one can change society merely by producing open code and design, while remaining subservient to capital, is a dangerous pipe dream” (Bauwens and Kostakis 65). In other words, casually open sourcing designs does not lead to a commons-based economy, as the real work comes in the designing and growing of the institutions that infuse them with purpose and value. Given that this “disruption point’ has not yet been reached, what needs to happen first? There are some immediate obstacles to be resolved, such as creating a map and documenting all existing WikiHouse-derived projects. Such a depository of blueprints would literally serve as a “Wikipedia for houses”, and as living proof of the project’s viability. The other pending priority is the development of BuildX, a parametric software for the customisation of the designs, and making them “ready to print”, enabling a higher adoption rate. Only then will the promise of WikiHouse to deliver affordable, adaptable and dignified housing to the masses be met to any substantial degree, marking the beginning of tangible impacts for sustainable built environments, (socialised) economics of housing and an architectural practice driven by the grassroots.

The page was created with Mobirise