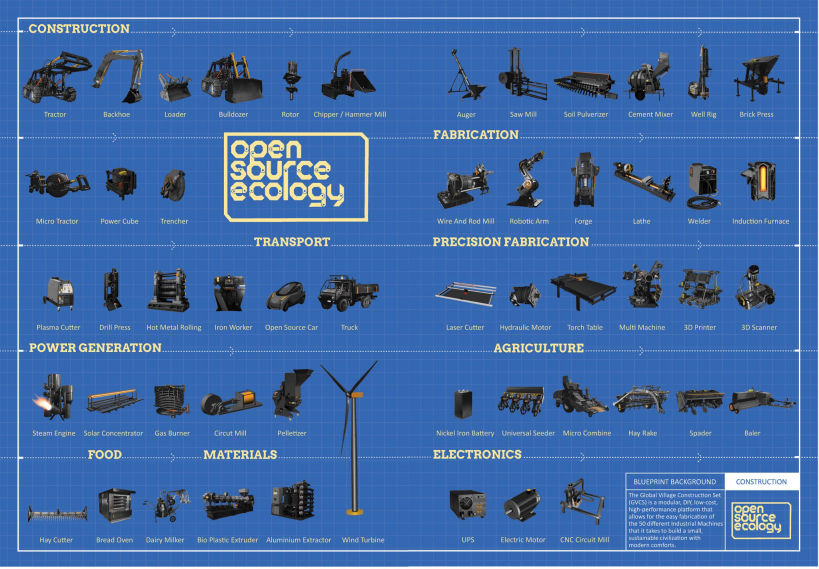

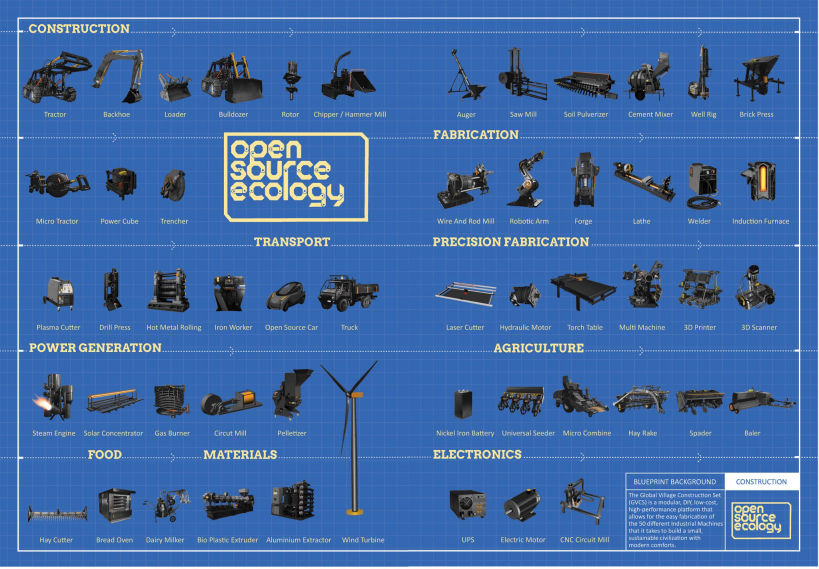

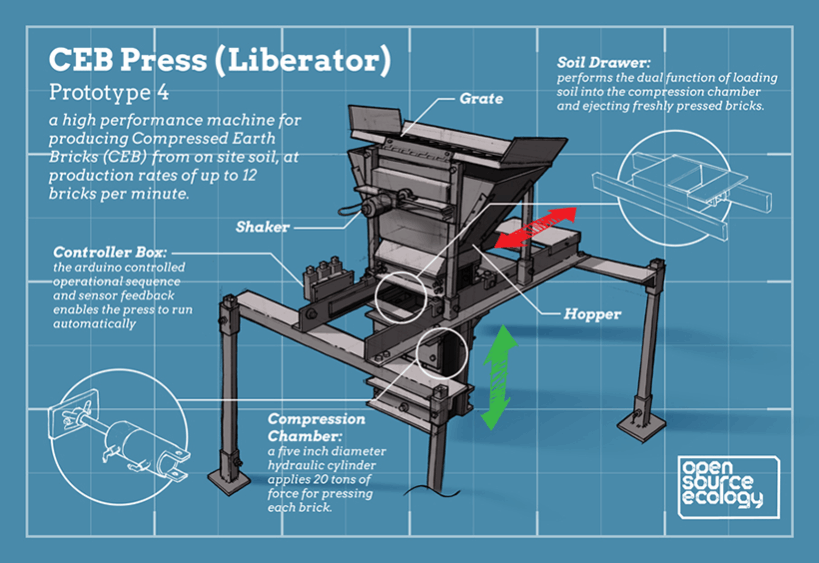

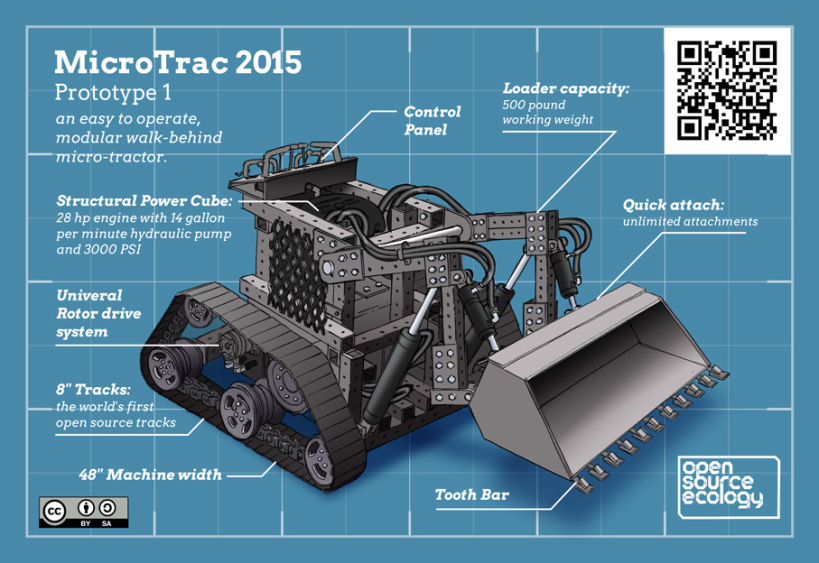

Fig. 22. Blueprints of the Global Village Construction Set

The website of Open Source Ecology (OSE)[1] carries a header: “open-source Blueprints for Civilization. Build Yourself.” Open-source and blueprints are familiar concepts in this study, but applied to the vastness of a “civilisation”, the slogan comes across as hyperbole. It wants, however, to be taken literally, and the blueprints developed by OSE are in fact not limited to the design of some machines, but claim to provide designs for the entire social infrastructure. In this sense, OSE professes to be the ultimate design project, taking counter-industrial intentions to a meta-level and proposing a complete package. The name itself hints at these broad ambitions: instead of specific tools or machines, it refers to the thing to be open-sourced as “ecology”. Given that OSE is slightly older than the other case studies, it has generated much more interest and controversy, and also recapitulates previously discussed dimensions: peer designing and modularity, open blueprints and development roadmaps, and finally, machines and makers. Rather than adopting the same methods that were employed to study the other cases, it is more appropriate to study less its technical specifics, and more its broader politics. This first section of this chapter focuses on these societal discourses of OSE, comprising an analysis of the problem within our current civilisation, as well as the pathways proposed to replace it.

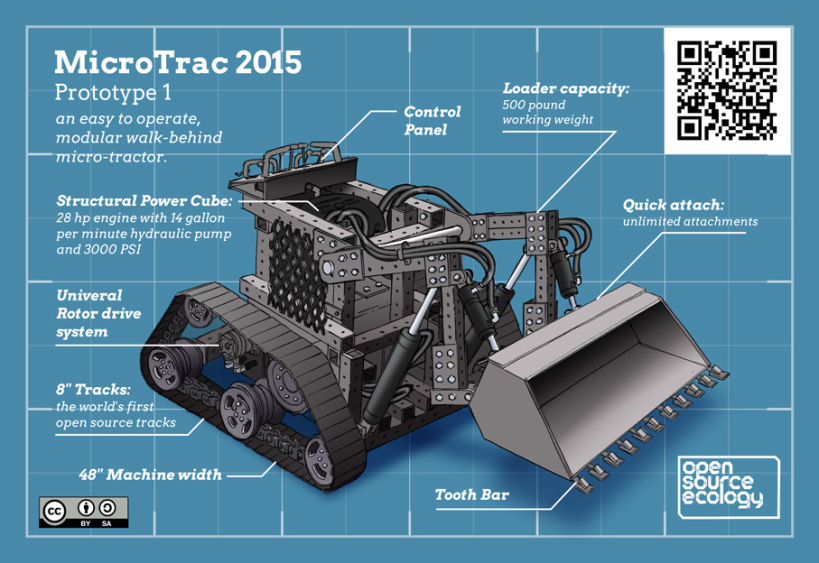

OSE captured considerable attention thanks to the 4-minute TED Talk delivered in 2011 by its founder, which attracted more than 1 million views. In the typical TED Talk fashion, Jakubowski begins his presentation with his personal journey, which took him from a PhD in fusion energy to becoming a “farmer and technologist” (Jakubowski 00:10). Disillusioned by academia, and being an idealist at heart, he stated a farm in Missouri, but soon discovered that the economics of farming did not favour small-scale, sustainable production. The tractor he invested in required expensive repairs, and he could not afford any additional costs at the bootstrapping stage of his project. In his words, “the truly appropriate, low-cost tools that I needed to start a sustainable farm and settlement just didn’t exist yet” (01:05). Rather than giving up on his ambitions, he decided to build himself the tractor from scratch —a leap of faith into something in which he had no prior skills. Achieving his objective, he concluded that “industrial productivity can be achieved on a small scale” (01:40), and shared his design blueprints online, with other contributors starting joining him in the design and prototyping of the machine. This experience gave him the confidence to launch the Global Village Construction Set project, expanding the applied principles to other agriculture and construction equipment, energy supplies and manufacturing tools. According to OSE, these machines together constitute “a set of the 50 most important machines that it takes for modern life to exist”, or “to build a small, sustainable civilization with modern comforts” (OSE, Machines).

The machines themselves will be examined in the next section, but what is meant by civilisation? And why uncritically endorse “modern life” as such? The answers to these questions can found in the “Civilization Starter Kit v0.01” – a 300-page guide released in December 2011 as a “Christmas Gift to the World” (OSE, Civilization). The foreword, written primarily by Jakubowski, is the key document explaining the OSE paradigm, and the vision and mission statements of the project. At multiple instances, it is argued that we live in an absolute abundance of natural resources, summarised as “rocks, plants, sunlight, and water” (6), but paradoxically in an artificial material scarcity, and this contradiction is attributed to the failure of centralised production to distribute these resources, in turn leading to deprivation, conflict and suffering (7). Perhaps “modern civilisation” is unable to deliver benefits after all? No motives are given for the artificial scarcity and centralised production, but only vague expressions such as “because of the way human relations have evolved” (OSE, Practical 0:11). Such euphemistic expressions reveal a certain reluctance to criticise capitalism explicitly —perhaps as a safeguard against mainstream recognition— which may explain why optimistic mainstream business magazines christening the project “the blueprints for open-source capitalism” (Coren). Nonetheless, the mission statement remains ambiguous, describing this “third economic option beyond capitalism or socialism” as follows: “to create an open-source economy —a collaborative economy that optimizes both production and distribution— while providing environmental regeneration and social justice” (OSE, Civilization 6). The choice of the word “optimisation” suggests a scientific approach to determining the most effective way of reaching reach a rational configuration, whereas justice could be understood to refer to a political desire to deliver fairness. Being both pragmatic (intending to tweak the existing parameters) and idealist (standing for ethical and political absolutes), OSE does not want to give up on what has already been acquired through industrial modernisation, but seeks rather to radically alter its organisation to deliver social and ecological sustainability: “industry no longer needs to occur in the form of toxic wastelands, but instead, eco-industry; on a human scale, serving the needs of people —not centralized industries competing for world domination” (7).

This vision is best encapsulated in the slogan and methodology “Design Global, Manufacture Local (DGML)”, which synthesises borderless collaboration in knowledge production and an ecologically responsible relocalisation of manufacturing in micro-factories. Referred to also as “cosmo-localisation”, it distinguishes between specific modalities for the sharing of “light”, non-rival, immaterial resources globally (building and maintaining a knowledge base for distributed fabrication), while making use of “heavy”, rivalrous, material resources locally with “specific local biophysical conditions in mind” (Kostakis, Roos, et al. 928). Geographical proximity to resources and/or end-users is intended to eliminate global transportation of goods and potentially complement an increased stewardship of land and resources (Kostakis, Latoufis, et al.). Instead of becoming extracted from their context and abstracted by the global commodity markets, resources that are grown or salvaged (and waste disposed of) in one’s proverbial backyard have a better chance of being responsibly managed than the sustainability roundtables of global conglomerates. Remedying the “rust belt” wastelands and broken working-class prosperity left behind by delocalised factories, this model brings designers and makers together with a sensible rootedness in a place and a community, which goes hand-in-hand with boundless coordination and cooperation opportunities. This combination is available neither to artisanal craftsmen nor to corporate factories (P. Moore 88), but is profoundly transformative for both. Cosmo-localisation implies that “one community of productive commoning on one part of the planet also can and should support other communities of production and commoning in another part of the world, through the development of a global design commons that democratizes production” (Bauwens and Ramos 4).

OSE appears to be prime example of a cosmo-local, counter-industrial ethos, and in fact predates the theorisation of the “Design Global, Manufacture Local” methodology. The concept of openness appears to be familiar as a result of its commonalities with previous case studies: it is conceived as “open access to economically significant information —product designs, techniques, and rapid learning materials for achieving this” (OSE, Civilization 6). Such an approach is meant to accelerate technological innovation and to provide an efficient economy in which resources are not wasted in competition. This open-source economy is described as being “based on widely accessible information and associated access to productive capital, distributed into the hands of an increased number of people” (11). These objectives carry strong similarities with those put forward in the cult counterculture publication Whole Earth Catalog in the late 60s, which promised to provide “access to tools”. The decentralisation of the manufacturing infrastructure is the core of this proposal, since it denotes a socialised rather than techno-centric model for the economy. In other words, instead of envisioning the future of manufacturing as solely as machine-driven (as in full automation, Internet of Things, or digital fabrication), it advances a human-scale, maker-driven transition into a new economy. The tone reaches a proselytising (if not New Age) peak when expressing the prospects of an open-source economy:

There are three stages of progress being projected here: technical capacity, personal liberation and material abundance. First, the primary task that lies ahead of OSE is the reorganisation of productive forces by distributing the tools to the makers. Once that is achieved, people are supposed to become better humans, and autonomous, skilful and responsible individuals who seek self-actualisation. This in turn is expected to deliver a sustainable, peaceful and prosperous society. Similarly, it is argued elsewhere that post-scarcity will be achieved “when we’re connected more closely to the natural resources from where all the wealth comes, by the fact that we have the means and the tools to transform those resources into the feedstock of modern civilization” (OSE, Practical 0:53). This is an exceptionally ambiguous affirmation, recognising ecological connectedness and simultaneously endorsing the industrial ideology of nature as mere raw materials. The same problematic relationship is also present in the causal link established between the acquisition of productive power and the lifting of material constraints – if anything, increased productivity leads to an overexploitation of resources. More worryingly, OSE affirms —with little explanation— its belief that the substitution of rare, strategic resources with locally available options is possible, hence the immaterial abundance of productive knowledge could automatically translate into material abundance. That said, there seems to be a step missing in between – a social-political project that negotiates between technology and ecology that is alluded to in the following interrogation: “Survival, with the awesome technology we do have today, should not take a lot of time. (…) What if we could survive and thrive up to a modern standard of living with two hours a day of work and from local resources? How would that be?” (Jakubowski qtd. in Eakin). The liberation of free time is perhaps the only politics OSE unambiguously stands for, with an early synthesis of all these positions best encapsulated in the original version of the project’s values statement, dated 2003:

The liberation of time by guaranteeing the essentials of life through technology is certainly not a novel idea, and will be explored further in following part. In contrast to ecomodernist Prometheanism, in which technological sophistication is out of reach and out of bounds for most humans, OSE does not champion modern civilisation as such, but rather pursues the goal of civilising technology, of domesticating its feral, unbridled character that is usually taken for granted. To some extent, this may explain the widespread and enthusiastic reception that the project has enjoyed since the TED Talk. At the intersection of sufficiency and convenience, OSE promises “a few critical yet sufficient technologies for survival as a species” (OSE, Civilization 26). It cultivates a practical-utopian ethos, appealing simultaneously to DIY ethics and entrepreneurial spirit, half-way between the appropriate technologies and the reappropriation of technologies. More than an engineering challenge, it sees itself as an activist endeavour, claiming that “OSE has a good chance to change the world” (19) and “the goal of OSE as a movement is to produce disruptive change” (20). More than a design project, it professes its desire to “contribute to the creation of open culture, where sharing and collaborative development is valued over greed and exclusiveness. This type of culture promotes life and growth, as opposed to fear-based aggressiveness” (276). Whether these laudable discourses can translate into coherent practices is yet to be explored, which would involve a study of the proposed designs and their working prototypes.

[1] Most of the quotes in the following sections are probably written by Marcin Jakubowski, although attributed to Open Source Ecology (shortened OSE).

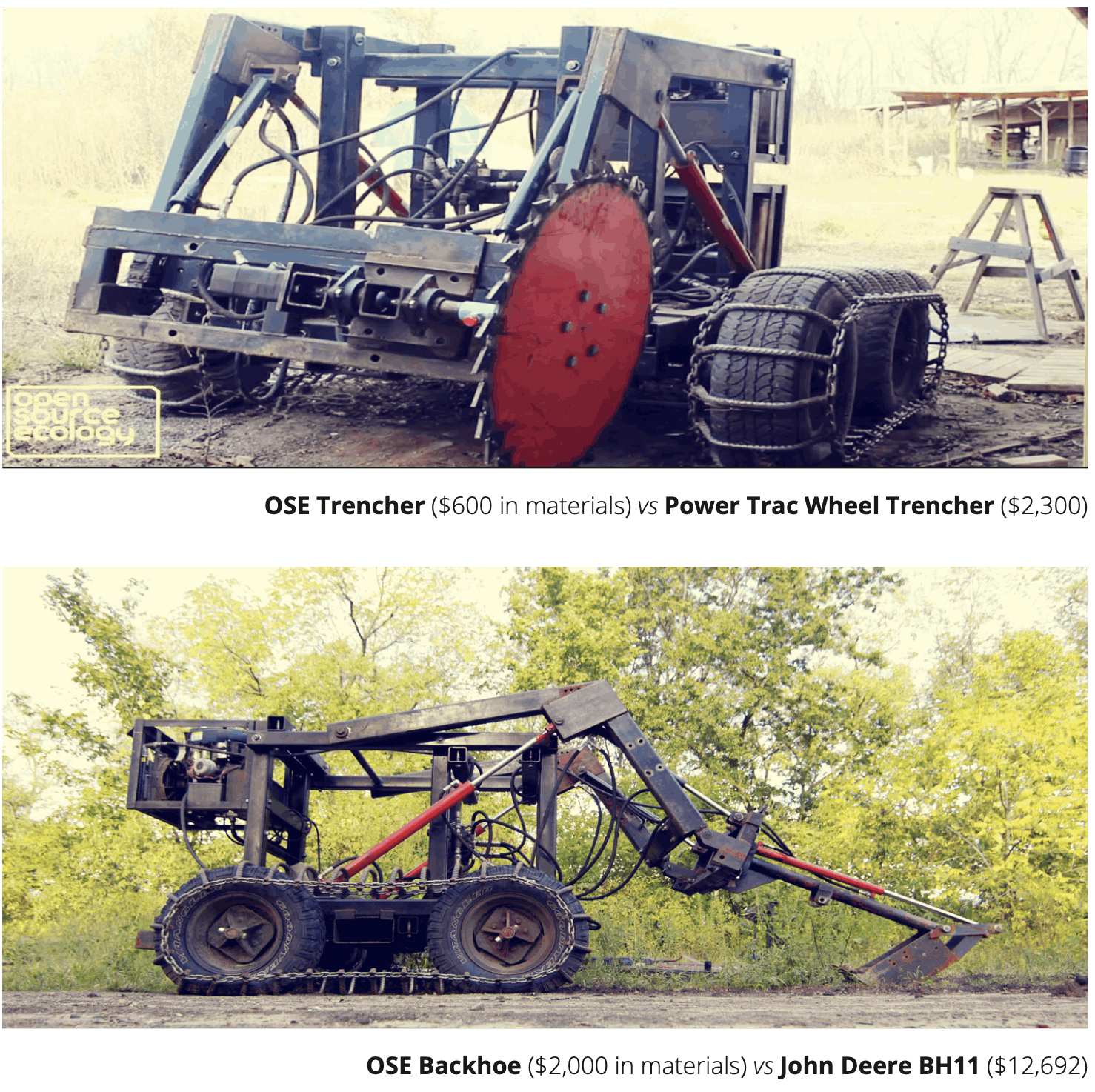

The Starter Kit poses the question, “So, You Want to Build a New Civilization?” to makers who are eager to get involved (OSE, Civilization 16), but the proverbial Rome cannot be built in a day, and there are multiple challenges ahead. Building a civilisation starts with the arduous task of completing the Global Village Construction Set (GVCS) [fig. 22], followed by a “viral replication” of the machines by communities around the world. This is undoubtedly a vast enterprise, but then again, so was Wikipedia a little more than a decade ago. This section explores the difficulties encountered in the earliest stages of development of this venture. The GVCS was conceived as an “enabling technology base” in the domains of agriculture, energy, housing, transportation and manufacturing (OSE, Civilisation 19), and was limited to 50 essential machines to give the project an achievable goal. These were “selected based on their large economic significance” (13), which was determined on the basis of a technique involving the meticulous scoring of different parameters, such as market or affected population size, livelihood creation, time liberation and localisation potential (OSE, Wiki, pt. ”Product Selection Metric”). It remains nonetheless an arbitrary selection, which excludes, for instance, the sewing machine, a key technology for women’s economic emancipation, both historically and around the world. When asked about its rationale, Jakubowski deflects the question, stating that he would rather be building the machines than discussing his list (Reversing). He elsewhere admits that the list is not meant to be an authoritative selection, but rather as a trigger for the imagination. By any measure, 50 machines remains an unapologetically ambitious objective, with which both “a shining example can be set, and a solid economic foundation can be laid” (OSE, Civilisation 26). Ultimately, instead of being regarded as strictly individual machines, the set must be appraised as a synergetic whole, “because new machines can be built from existing machines, the GVCS is intended to be a kernel for building the infrastructures of modern civilization” (OSE, Mission). In a technological recursion, some of the machines are essential tools for the building the next ones. Machines are meant to give makers the power to build distributed productive capacity, thus enabling a broader adoption of a more widespread maker culture.

A few clarifications on what is meant by “means of production” are fundamental for understanding the counter-industrial paradigm outlined here. The means of production consist of the instruments of labour (tools, machines, buildings, infrastructure) and the subjects of labour (knowledge, energy, materials, land), which together with labour and capital, constitute the factors of production. The main preoccupation of this chapter falls under the “instruments of labour” category, in which the “means of production” are considered, in the narrow sense, as tools and machines, as design products themselves. In an industrial mode of production, machines occupy a highly influential position, determining the productive investment of capital, the relentless exploitation of resources and the erosion of the primacy of labour in production. Since machines tilt the (im)balance between labour and capital towards the latter, the modalities of how the means of production are themselves produced deserve particular attention. As exemplified by OSE, the preferred counter-industrial strategy to revolutionising the mode of production is the self-production of the means of production. What is meant by self-production is decreasing dependence on conventional means, and increasing the autonomy and self-reliance in the provision of these means. As an overly simplified comparison, if controlling the means of production in the 19th century implied the takeover of factories by the workers themselves, the 21st-century equivalent can be seen as the creation of a multiplicity of micro-factories by the makers. The challenge that OSE attempts to respond to with its GVCS machines is the creation such micro-factories from scratch without having access to the factories in the first place.

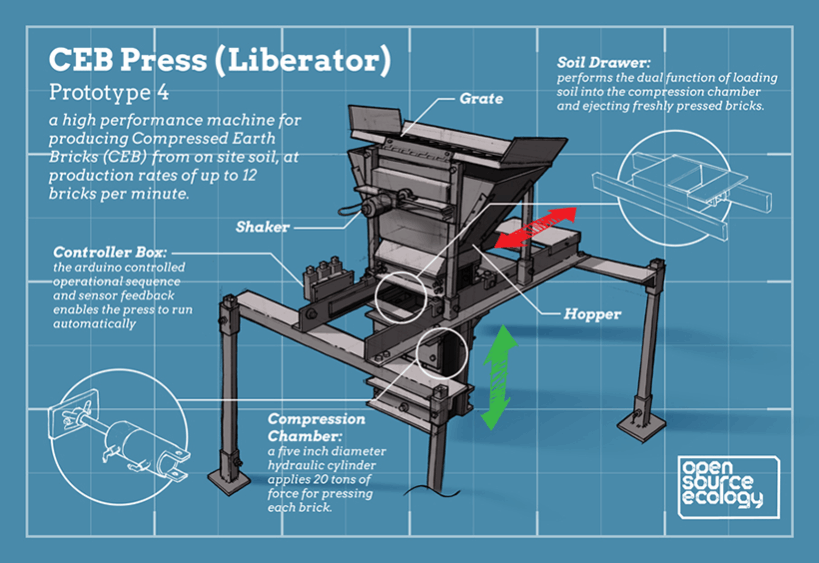

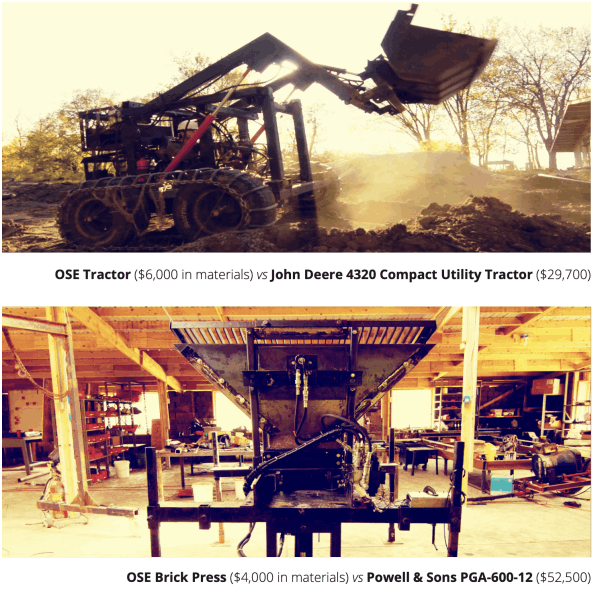

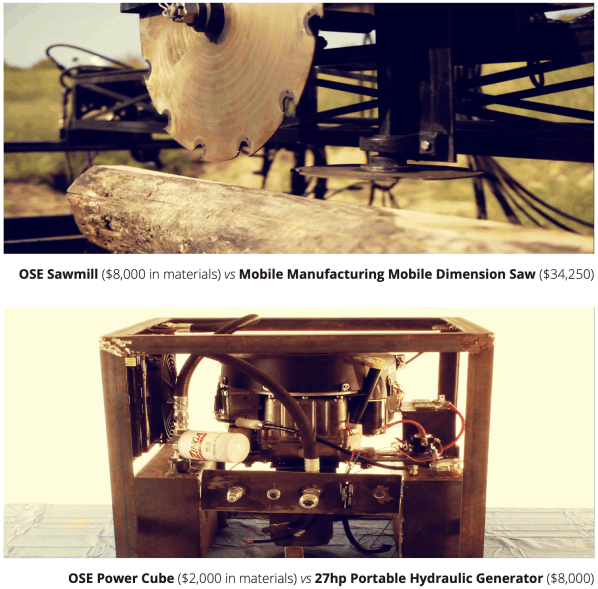

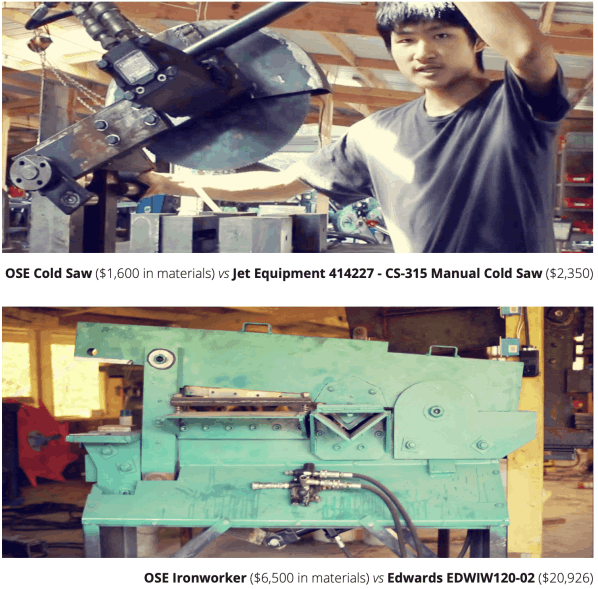

An extensive list of 49 criteria are provided as the guiding design principles behind GVCS machines, ranging from the predictable ones like open-source, modular or closed-loop, to more original ones such as “permafacture”, “appropriate automation” and “nonviolence” (OSE, Civilisation 276-290). The principles of low-cost, simplicity and sufficiency are demonstrated through a comparison with industrial standards. On average, the material cost of GVCS machines (minus labour) are estimated to be one-eighth of the market price of their commercial counterparts [fig. 23], although at the same time it is yet to be seen if they can all deliver the high performance and efficiency required for their adoption. Another crucial aspect is the principle of the division of labour, as opposed to individual production and the use of the machines: “all of the technologies may be adapted to an individual’s use, but division of labour is more desirable for achieving a complete economy in a community” (278). Following Dunbar’s number (the number of people who can sustain stable and meaningful face-to-face relationships), the recommended size of the community is the “village scale of about 200 people” —hence the name Global Village. In other words, just like the blueprints, the machines themselves are meant for sharing, which in turn may imply that their uses and benefits are also to be shared among the community. One of the early adopters of the tractor LifeTrac 5 – Our School within the Blair Grocery urban farming community project in New Orleans – attests to such collective use. The school’s students claim that before the arrival of the tractor, everyone was reluctant to engage in composting, but the rugged and robust machine made them all motivated to take on the task (Reversing). As another example, the machine closest to completion – the Compressed Earth Block (CEB) Press prototype 7 – produces up to 10 bricks per minute that are used for the building of walls, and by extension, the construction of habitat. As of the end of 2014, 100 GVCS machines had been replicated —a modest start for a new civilisation.

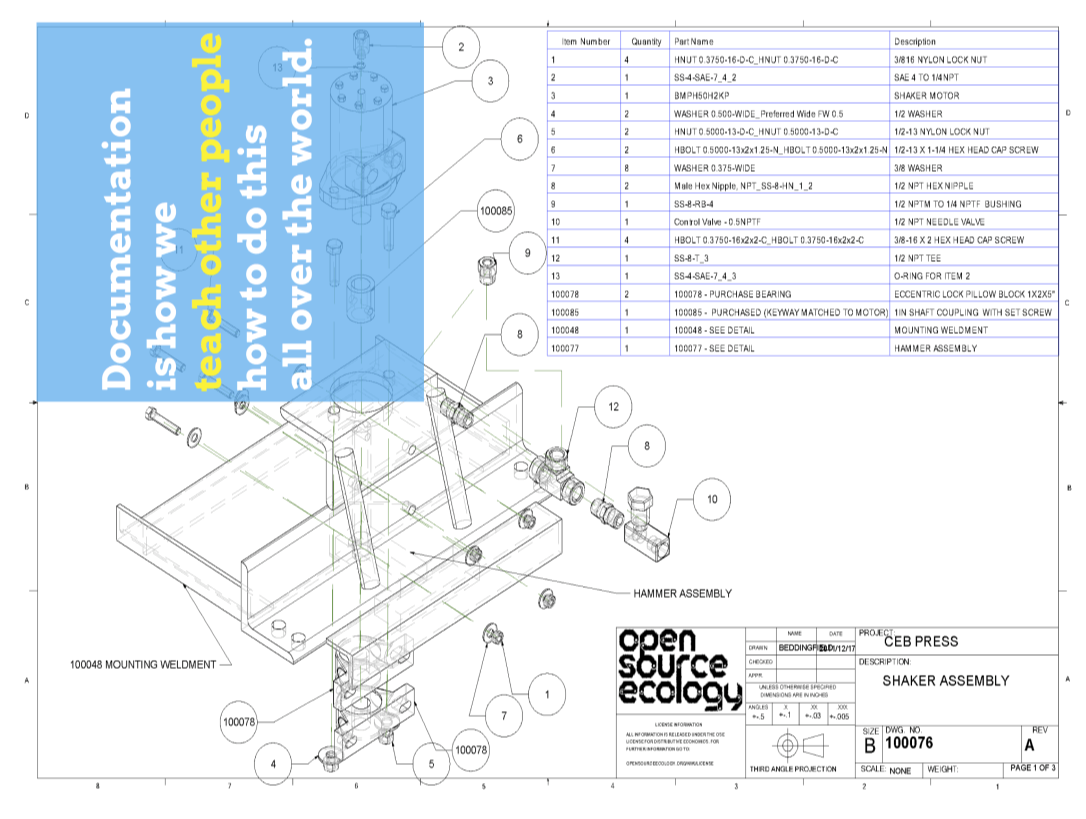

The first page of the Civilization Starter Kit proclaims over a technical drawing: “Documentation is how we teach other people how to do this all over the world” [fig. 24]. The thing to do —to start a civilisation— is literally put in the hands of makers, machine builders that follow the instructions manual. Of course, next to the rather static medium of a PDF file, more up-to-date and collaborative channels are used to distribute the blueprints of GVCS, namely a Wiki and a YouTube channel. Once complete, the documentation is expected to demonstrate “a replicable, open-source, social production model for a given machine” (OSE, Machines). This requires much more than only sharing the blueprints, as the complete know-how must be provided if financially sound and socially viable business models are to be created around the machines. OSE calls this Distributive Enterprise: “a transparent enterprise that promotes —at the core of its operational strategy— the capacity for others to replicate the enterprise without restrictions” (Thomson and Jakubowski 62). It should be noted that this “distributive” model is not merely “distributed” (in the sense of decentralised), as the primary purpose is to share knowledge, to create livelihoods and to spread the wealth. The success of such an enterprise is measured not in terms of the units sold or the profits made, but by the number of replications. OSE has an ambition to scale GVCS and lead the way for open-source enterprises to become nothing short of the “next trillion dollar economy” (OSE, Community pt.Support). This is based not on a belief that such enterprises can effectively compete for a larger share of the market, but on their ability to short-cut of how business expansions traditionally occur. Since “openness is compatible with the common good” (OSE, Development pt.Economics), this model presents an ethical advantage that can be expected to encourage contributors also to share their best practices. The proposed OSE Licence, covering both the design blueprints and business models, waives all rights, and puts the knowledge in public domain, but with the additional condition of adherence to the ethics of Distributive Enterprise. Considering the level of detail that manifests elsewhere in the project, this legal framework appears surprisingly imprecise and incomplete, when compared, for instance, to the Peer Production License explored in the previous chapter.

What has been the progress over the years? How close to completion is the GVCS, and how widespread its adoption? The explosive interest that followed the TED Talk must have boosted confidence in the project so much that the Civilization Starter Kit professes unrealistically high ambitions. Raising $5.5M in funds, developing all the machines in parallel, releasing a beta version of the full set by the end of 2012, and even more optimistically, “if things continue as they are now, we may be done ahead of schedule” (OSE, Civilisation 21). The first (and so far only) Annual Report, published in 2012, pushed back the completion date to the end of 2015, while also promising to develop documentation standards and to streamline collaborative design principles by that date, however none of this materialised in the following years. While the existing machines have been improved, very few others have been taken forward, and the network of the thousands of communities replicating the machines has failed to materialise. One of the obstacles encountered (that still remains unresolved) is the realisation that open blueprints alone are not enough for replication, as the learning curve is still too steep and intimidating for beginners. OSE recently attempted to remedy this situation by initiating one-day replication workshops. “One day is a metaphor —a sign of hope, a sign of radical efficiency,” confesses Jakubowski (qtd. in Eakin). While this approach displays a better outreach potential to producers and users, it falls short of making them any more capable of designing and developing the machines further. Without continuously broadcasting the knowledge and collecting feedback, engaging decentralised contributors in the improvement of the blueprints remains an unsolved issue. In comparison, initiatives like L’Atelier Paysan or FarmHack (both specialised in open-sourced farming equipment and machines), which strictly document existing grassroots innovations, appear to be much better followed and up to date than OSE. In this regard, it would seem that nobody actually needs any of these brand new machines designed from scratch, as rather than satisfying immediate necessities, they would appear to respond rather to some hypothetical needs.

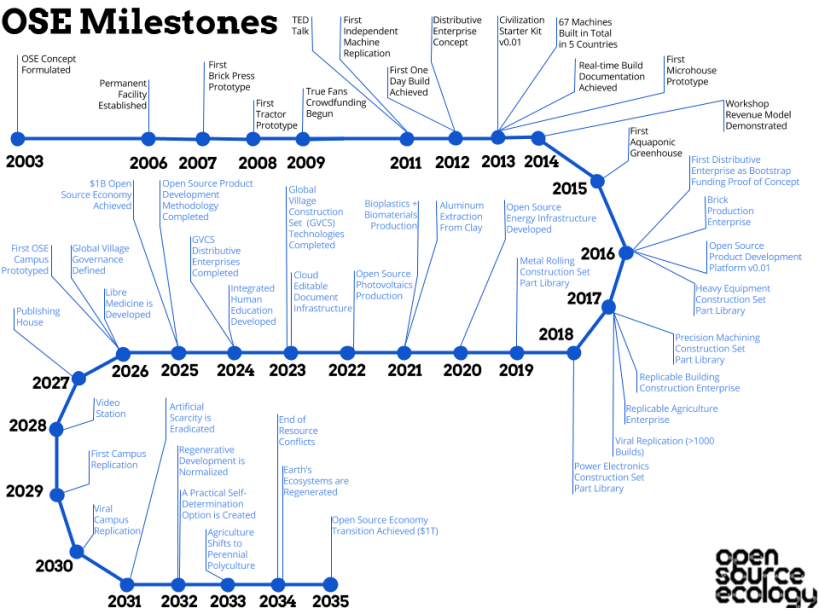

Judging by the state of the online documentation, the project seems to be suffering from a general state of neglect: the forums are unused, the blogposts are sparse, and the wiki lacks updates. Does all this imply that the OSE project has failed? In a TED interviewed in 2014, Jakubowski admitted “… it’s more like a two-decade project than the two-year project I initially imagined” (qtd. in Eng). Since then, attention seems to have shifted away from the machines to the development of eco-housing and aquaponic greenhouses, under the banner of “Open Building Institute”. That said, there is no giving up on the excessive ambitions. A roadmap graph recapitulates the milestones until 2015, and anticipates future achievements every year until 2035. It projects the viral replication of more than 1,000 machines by 2017, the entire GVCS blueprints to be completed by 2023, and the first self-sufficient OSE Campus prototyped in 2026 and replicated around the world by 2030. The final five year plan is nothing short of a great leap into utopia: “artificial scarcity is eradicated”, “end of resource conflicts” and “earth’s ecosystems are regenerated”. [fig. 25] As much as I appreciate the vision of the project in prose, without any distinctions between past achievements and future objectives, I find this linear roadmap to be rather misleading (if not downright dishonest). Considering the glaring mismatch between the current state and future roadmap of OSE, between what is prefigured and what is speculated, this should cast serious doubt on the reliability of the project. These not only indicate technical difficulties in getting OSE off the ground, but also a lack of self-reflection and path correction, revealing organisational troubles that can be best understood by studying, in the following section, the design of the project itself.

The short video “Build Yourself” opens with a tracking shot of mouldy walls, rusty pipes and broken windows —a haunting Rust Belt landscape left behind by off-shored manufacturing. [fig. 26] Meanwhile, a voice-over by Jakubowski describes the bleak landscape of the commodity-machine: “Right now, the world’s productive power is controlled by a few giant corporations. Products are expensive, their designs are secret and to make things worse, we’re now seeing the same companies engineer their products to fail over time, simply to increase profits” (OSE, Build 00:11). As Jakubowski voices his critique of monopolies, intellectual property and planned obsolescence, a sunset over a derelict factory fades out, and is replaced by a new, spacious workshop where GVCS is being tested, “From our location in Missouri, we’re developing low-cost modular tools that anyone can build, and we’re sharing our designs on the Internet, free of charge” (00:45). Time-lapse shots of volunteers welding machine parts are complemented with digital blueprints of yet to be realised machines. Meanwhile, Jakubowski praises the advantages of open-source: “you produce the plans, you give a lot to the community and then stuff starts coming back, then the products get better and better, everybody wins” (01:40). To illustrate this point, the video introduces a lush green setting in Indiana featuring a duplicate of the CEB Press – one of the first GVCS prototypes. Its maker, accompanied by what seems to be his partner and newborn child, claims: “I’ve never built a house before, I’ve never done hydraulics before, but it seems to be working” (02:23). Not only had he built a working machine, he also suggested some improvements to its design. The video concludes with Jakubowski’s call to arms, encouraging potential makers to unite and overcome their perceived limitations:

Dispel the illusion of incompetence, Jakubowski argues, and both personal and social change are within reach. If we would only build and use these machines, he suggests, we would become all-round maker subjects at the intersection of inventor, designer, engineer, craftsperson and repairperson, and could thus overcome the limitations imposed on us. With no mention of systemic inequalities or different abilities (and the solidarities among them), “building oneself” sounds first and foremost as self-improvement advice for “self-made men”, as if their can-do attitude is a precondition and their collaboration is merely incidental. Instead of recognising interdependence as a principle and engaging in distributed peer production, priority seems to be given to self-reliance and entrepreneurial leadership. This strikes me as being more of an individualist-libertarian stance and less of a vision of collective emancipation through the building and growing of social relations. Considering OSE’s preoccupation with being exemplary and prefigurative, it is even more pertinent to identify the organisational characteristics of OSE and the meta-design of the project. The point here is certainly not to reveal the tiniest of inconsistencies in order to discredit the entire project, but to assess if its social infrastructure stands as a blueprint —however imperfect— for communities seeking to follow its vision and replicate its principles.

How is OSE structured? How are decisions made? How are conflicts resolved? To understand OSE as an organisation, there is no better place to begin than the Factor e Farm (FeF) in Missouri, where the project was initiated and is still being pursued. The 12 hectares of arable land bought by Jakubowski himself is the main development facility for GVCS, where the prototypes are built and tested first-hand, along with the feasibility of the “rebuilding communities from the ground up” claim (OSE, Civilisation 13). Neither a hippie commune nor a high-tech start-up, it has been likened to “a living science fiction novel, a combination of a return to roots and a futuristic vision” (Thomson and Jakubowski). This is where OSE is supposed to spill over its core technical mission to become a comprehensive social project:

Described as being “in the middle of nowhere” (Eakin), the choice of location for the Farm does not seem to have been made with any strategic considerations, such as being close to a particular demographic of potential collaborators. Instead, it is no exaggeration when the project describes itself as “an experiment of trying to recreate civilization from scratch” (OSE, Practical 01:51), at a remote location (and yet, conveniently, near enough to an international airport). This choice is described as a “neo-subsistence lifestyle” (OSE, Civilization 278), an off-the-grid, autarchic ethos that is certainly more widespread in the United States than elsewhere. Jakubowski’s preference for setting a pure example over practical considerations is reported by multiple collaborators. There are cases of being strictly dependant on solar energy stored in batteries rather than being connected to the grid (even when the batteries are depleted and the work is brought to a halt), refusing the provision of water from the grid, and digging a difficult and unreliable well, which was responsible for making everybody ill (Vance). In the words of a former collaborator, “[Jakubowski] was so stuck on being off the grid that it was becoming an obstacle to work” (qtd. in Eakin). This uncompromising attitude conjures up an image of survivalists “prepping” for the imminent collapse of civilisation – if you have your land and your machines, you can endure any crisis. This “lifeboat ethics” experiment would have been an interesting test of the viability of the machines once the GVCS is complete, but until then, being integrated and interdependent is a precondition for bringing the project success. In some sense, trying to bootstrap such an audacious project in isolation is like starting to write Wikipedia in a secluded monastery —a counterintuitive choice for what is presented as a distributive enterprise.

All these could be considered as tolerable hiccups or missteps if the community living and working together demonstrated exemplary cohesion and harmony. However, it is widely reported that the Farm (and hence the project) has suffered from multiple mass departures of volunteers and contributors (Bauwens, 'Crisis'). One collaborator observed that “with a focus on machines and not on people, the vision has suffered” (Copley-Smith). Expecting contributors to dedicate themselves full-time to voluntary work under the pressure of extreme workload, with long days of labour and a lack of basic comforts —life at FaF has been a far cry from the projected goal of living with two hours of daily labour. The project has relied on the most idealist (but inexperienced) of followers until they are burnt out, as professionals with much-sought skill sets have been reluctant to commit to its unaccountable structure. In fact, for all the desirable vision of democratising production, there has never been any commitment to prefiguring such an ideal on-site. The project was hierarchically structured around the magnetic pull of a personal vision, never around any principles in which everyone is included and respected. Remarkably, responsibilities are organised like a conventional workplace: there are multiple titles, such as directors, managers and product leads, who all have specific duties and supervisory roles, and there is no mention of any kind of democratic principles, whether on-site or remotely. A Board of Directors has absolute control over the entire project, as defined in the bylaws of the non-profit corporation, but lacking the institutional forms in line with its professed goals, it could not establish a reliable and sustainable organisation with democratic control. Repeatedly, the reason given for quitting has been a conflictual relationship with Jakubowski – the de facto leader of the project and effectively the owner of the Farm itself. Some call his leadership “dictatorial” (Eakin), and note that his lack of (or unwillingness to develop) skills in growing a community has deeply damaged the project:

According to multiple sources, OSE succumbed to a toxic mix of a male-dominant culture, a cultish hierarchy, exploitative work and lack of accountability —a fate that is a far cry from its initial lofty ideals. In a review of what went wrong with the project, one researcher remarked that “OSE’s over-emphasis on technology ignores the ways in which power is maintained through infrastructure and its inequitable tolls” (Pasek). Similarly, after having endorsed and promoted OSE in its early years, Bauwens later commented that it never grow into a “true global open design project, since it was dependent on the leadership of one person in a particular locale” due to “the design of the project itself” (Bauwens, 'Crisis'). Not only has Jakubowski never acknowledged the fallouts publicly, he has also never felt the need to explain delays, changes of course or complete abandonments of objectives. OSE could have made a commitment to communicate honestly and learn from its failures, which would have been the greatest gift for designer and maker communities in allowing them to avoid potential pitfalls, as well as a way of eventually (re)gaining the trust of new collaborators. In the words of one ex-volunteer, “a vision as complex and ambitious as Open Source Ecology can only be achieved through debate, rigorous experimentation, genuine collaboration and a little love” (qtd. in Bauwens, 'Crisis'). Civilising technology does not come in a box, ready to assemble; it has to be grown from the ground up with people, and with civility.

Ultimately, it would be fair to conclude that OSE sought to do too many things at once. It could all at once be seen as a self-sufficient farm and an off-the-grid communal living experiment (but without a thriving community), as a peer-design studio and R&D network (while lacking widespread collaboration), as a start-up under a “visionary” leadership (though lacking a viable business model), and as an educational enterprise (for those who could afford it). Rather than dismissing OSE altogether due to its failure to meet its unreasonably grandiose ambitions, it would be much more valuable to consider it as a cautionary tale for future counter-industrial endeavours. In this light, it is particularly worrying that an overwhelming majority of media coverage of OSE has lacked any in-depth investigation, featuring only uncritical, positive portrayals of the project, which is presented as a shining example of maker machines. The same could be said about its appearance in exhibitions, such as the Istanbul Design Biennial, which featured a built tractor. It was devoid of context, with no relativisation made of its viability, and not having been used at all, it was more of an art piece in the white cube rather than a functioning prototype in the mud. Still, thanks to its unique exposure, OSE has been influential and motivational for many other projects, allowing them to gain confidence and to carry their ambitions further. While the Farm is certainly not the first experimental intentional commune to fall short of its promise, the vision seeded by OSE has flourished in other places.

I begin this section by sketching the contours of the broader debates on technological sophistication and material abundance, most notably, the long-standing controversy of technological unemployment. This allows me to reject particular perspectives of the post-work politics of full automation, and to focus rather on machines that enable makers in unprecedented ways rather than rendering them redundant. I follow the evolution of Precious Plastic to explore the emergence of a new breed of crafts that provides both social livelihood and ecological benefits.

Designed with Mobirise website software